theartsdesk Q&A: Opera Singer Sir Thomas Allen | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Opera Singer Sir Thomas Allen

theartsdesk Q&A: Opera Singer Sir Thomas Allen

This week the great lyric baritone celebrates his 40th anniversary role at Covent Garden as Don Alfonso

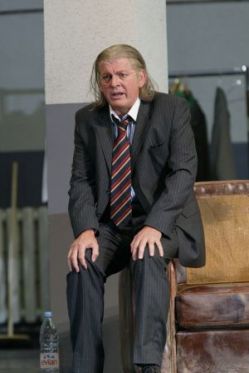

The landmarks continue to mount for Sir Thomas Allen (b. 1944). Awarded the CBE 22 years ago and knighted a decade later, the great lyric baritone notched up his 50th role at Covent Garden in 2009 and this week in Cosi Fan Tutte he celebrates 40 years with the Royal Opera House. In the same week he takes up his new appointment as Chancellor of the University of Durham. Indeed, although he has sung everything from Monteverdi to Onegin to negro spirituals, in his speaking voice he remains a son of County Durham. The first consonant of "opera" is unstressed to the point of inaudibility.

In a career ranging across languages, centuries and continents, the one constant has been his great gift for inhabiting a role not only as a singer but also as an actor. And he is still producing novelties. IN 2008, bizarrely under the direction of Woody Allen, he added Gianni Schicchi to his repertoire. In 2009 he sang alongside the voice of Stewie from Family Guy in the Proms’ tribute to the great MGM musicals. In a wide-ranging interview he talks to theartsdesk about a life spent in Covent Garden and beyond.

JASPER REES: So in your 40th year you've sung more than 50 roles at the Royal Opera House.

SIR THOMAS ALLEN: I’ve no idea. Somebody is keeping count around here, one of the trainspotters. They range from five-hour operas to a minute-and-a-half appearance.

What was that?

I think it was a Scythian in Iphigénie en Tauride. He comes on and gives a weather report and goes off again. It’s a very, very brief appearance.

Same pay?

Same pay?

Well, at that time when you’re a member of the company they’ve got you, you’re in hock to them so you just do it. You can take the night off if you wanted to as well. It works the same way. No, I think we’ve jointly had our money’s worth over the years. Can’t complain. Swings and balances.

If someone had told you in 1971 that in very nearly 40 years you would be singing your 50th role at the Opera House, what would have been your reaction?

Well, there would have probably been several reactions. If they’d told me it would be Faninal in Rosenkavalier I might have stopped right then (Pictured above right: Sir Thomas Allen as Faninal in Der Rosenkavalier © ROH / Mike Hoban). I was talking to a colleague of mine and said, “It’s one of those roles that’s quite tricky and engages the brain - what remains of it - and it would be nice if I were coming to it now, revisiting it after 20 years.” And he said, “Come on, be honest, if 20 years ago you’d been offered the role of Faninal, what would your gesture have been?” And so I made a rude Italian gesture, because that’s the truth.

Which one?

It involves a hand and an arm. Hopefully the arm is not false and goes flying over your shoulder. But no, I’d have been amazed. I remember just shortly before 1971 I used to sing a lot of concerts around the country and people would say, “Ooh, when you’re singing your first role at Covent Garden we must have tickets. Let us know when it’ll be.” And I thought they were talking to someone else. It’s been a journey of amazement really. I had no idea that what has happened in my life would have taken place. It’s all come as a big surprise.

Was it in any shape or form an ambition to have this kind of career? Would you not have had the gumption to form such a grand ambition?

I wouldn’t have had the gumption because I didn't know the nature of a music career or a singing career. I grew up in Seaham, a mining community in Durham. There weren’t many opera singers came out of my town. There were local singers but you didn't do it for a job. If you were in the local grammar school, you got through the 11-plus - which is what I did – you then went on to college or university or whatever it might be. We had a headmaster who actually encouraged you to graduate away from that community. He wasn’t mad on it, I look back in reflection now. He wanted us all to widen our prospects and horizons and see the rest of the world. I remember looking at newsreels at the pictures and seeing a big aeroplane arriving in London somewhere – probably it was still Croydon, I’m not sure – and a man called Beniamino Gigli getting off the plane because he was coming for the London season. And that was it. That doesn’t register. He might as well have been from Saturn or Neptune somewhere. It was that foreign, the concept. I had never imagined what that life must be, who this man was, and what was going on in a theatre such as this.

I was very lucky in several senses. Singing in general then had more street credibility than it seems to have now

And that was the case for quite a long time. I had no idea. Certainly at the age of 16 – I think it was around about then – I went to see at Sunderland Empire the Sadler’s Wells Company on tour performing Tosca. But even then I wasn’t curious or inquisitive enough to investigate what that was. We didn’t listen to the Third Programme at home. It was either Radio 4 or Radio 2. Two-Way Family Favourites on Sunday, that was it.

Did Tosca grab you by the lapels?

Yeah, it did. It made a big impression. In fact I got to know two of the people. The Tosca I got to know a few years after that and the Cavaradossi became a very good friend of mine some way down the line. It was Victoria Elliott who was a big star then, and a Welsh tenor, tough little fella, called Bob [Robert] Thomas who took an interest with his daughter once in a pottery class. She gave it up, he took it on and he became a potter. His career petered out. He was a tough, outspoken individual but I liked him very much and he made great pots. And he was also a very very fine singer. A colleague of mine – we were talking about him once quite a lot of years ago now – and he said, "Bob Thomas was the nearest thing I heard to Caruso” is what he said, which is rather extraordinary. Anyhow, that was the memory.

How much do you remember about that first production?

The first thing I did here was to understudy Onegin, which was early days for as big a role as that for me, but I got to know that cast who have been friends, those that survive, ever since. So that was memorable and that was a production that I went into rather further down the line with Peter Hall. I remember my first appearance onstage which was as Donald in Billy Budd and I understudied Peter Glossop as Billy Budd. And I can still remember standing on the stage for the first time, as opposed to the London Opera Centre where we did the early rehearsals. Standing on the stage one morning it was dark, and I think we came to a break in the morning’s rehearsal and the lights, the little candles, came on around the theatre and sentimental old me felt a tear gathering in my eyes. And I cried. It was an amazing thing to witness, to see this most beautiful theatre and to be involved in it, not knowing how long that involvement might last.

The first thing I did here was to understudy Onegin, which was early days for as big a role as that for me, but I got to know that cast who have been friends, those that survive, ever since. So that was memorable and that was a production that I went into rather further down the line with Peter Hall. I remember my first appearance onstage which was as Donald in Billy Budd and I understudied Peter Glossop as Billy Budd. And I can still remember standing on the stage for the first time, as opposed to the London Opera Centre where we did the early rehearsals. Standing on the stage one morning it was dark, and I think we came to a break in the morning’s rehearsal and the lights, the little candles, came on around the theatre and sentimental old me felt a tear gathering in my eyes. And I cried. It was an amazing thing to witness, to see this most beautiful theatre and to be involved in it, not knowing how long that involvement might last.

The sense of arrival was palpable.

It was. And surprising too because I had never planned to be involved in opera. I didn’t train to be an opera singer. I had no stage craft at all. I had to pick it up as I went along. I trained to be a singer.

What were the circumstances in which you gravitated towards the other discipline?

Money. I had to make a living.

You studied oratorio and Lieder first.

That was my life at the Royal College [of Music].

Was there an option to study opera?

I could have gone into the opera school. It didn’t have a great reputation at the time and I didn’t see myself doing it until some years down the line. I still towards the end, my last year there, saw myself as being principally a singer of recitals and oratorio as well, and occasionally making it to an opera house. And then I got the opportunity, because a baritone went missing – he took a job and was gone – they needed a baritone and I was the best one going upstairs in the rest of the college. I was approached and said I would do it. It might be good experience. So I did, I went downstairs and did one opera.

Which was what?

It was The Prima Donna by Arthur Benjamin, which I haven’t actually sung since, and nor has anyone else as far as I know.

Below: Sir Thomas Allen as Music Master in Ariadne auf Naxos, 2002 © Bill Cooper/Royal Opera House

However, it must have turned on a light.

However, it must have turned on a light.

Oh, it did. I enjoyed it. I felt an affinity with the stage. I couldn’t do my make-up and I didn’t do my make-up for quite some time - I hadn’t learnt anything of that sort. But the director of it recognised that I had a facility around the stage which was in a very raw state and could be developed and it went on from there.

Had you as a grammar school boy in County Durham already discovered a facility for stage acting?

No. I carried a gun in The Devil’s Disciple. I could march because I was in the church lads’ brigade but speaking verse, rhyming couplets or whatever else – it was usually Shakespeare we did at school – I had nothing to do with. I didn’t get onstage. I rather wish I had.

Not even to sing?

To sing I did.

How good a singer were you as a teenager at, say, 15?

Exceptional.

How good were you before your voice broke?

I was a good boy singer. I was head chorister in the church. But my voice didn't take time to break. I was head chorister at a practice one Thursday night and the following Thursday something happened in that week in between which I didn’t notice but they took the ribbon off me and I went and joined the men in the back row and sang the bass line. I went straight from treble to baritone. And I continued singing through school.

Were you individually tutored?

I was very lucky in several senses. Singing in general then had more street credibility than it seems to have now. We had a school choir and we all enjoyed that. And at the end of the year there would be a school concert, we’d sing choruses from Messiah or The Creation or whatever it might be. There was always the need for a soloist. There was always the recorder group and the school orchestra in which the French master played flute. It wasn't a great orchestra but I played an organ solo, I remember, and also sang a solo. I offered up a song which I sang and it clearly registered. And it was my physics master who played for me – Renaissance man personified – and then offered to give me lessons. I started lessons as a 15-year-old at school.

And was there ever any doubt that you would train in London?

Oh, it was never in my mind. I wasn’t aware of that concept. I continued for some time just thinking of pursuing science subjects which is what I was doing, towards a medical career, which was foundering more and more as time went on because I wasn’t suited at all to the sciences.

Is there any truth in the notion that your story was Lee Hall’s inspiration for Billy Elliot?

Is there any truth in the notion that your story was Lee Hall’s inspiration for Billy Elliot?

I think Lee Hall said that himself. Which is very very flattering, if that is so. I sang and it got noticed undoubtedly and the next thing I knew an HM inspector was at the school one day and I sang for him - the headmaster organised that – and he said, “Well, it’s very good. The course you should do is perhaps through King's and do a choral scholarship,” which wouldn’t have been me at all. But the headmaster then pursued it through another route. He got in touch with Durham University and Arthur Hutchings, who was the eminent professor of music there. I went to Durham one day in my school blazer and finally met up with Arthur Hutchings who listened to me and he organised an audition for the Royal College. I came down and sang for them and they took me because I had a handicap of three on the golf course. That was the question I do remember.

The Royal College took you in because of your golf handicap?

Yes, basically. I sang for the director and one of the teachers and they liked my voice. They said, “You’ve got this dilemma as to what you’re going to do with your life. What are you set upon and what are your other interests?” I said, “I play golf.” He said, “Do you play well? What’s your handicap?” And I said, “Three.” “Oh I think we have to take you in.”

Was coming down to London a leap into a terrifying unknown or did you take it in your stride?

Bloody awful. I hated it. I was very unhappy. I had really hardly ever been away from home. It was a very close-knit family, my mother and father and me. We lived in this little house and I loved them dearly, my father in particular, and I just hated getting on a train and going away from home. And I made their lives a misery. I was in a very dark house owned by an old lady in Stockwell and there was another old lady resident in there. It was just awful. I used to ring them in desperation trying to come home. It would have been so easy for them to say, “Pack it in, come home and just live here.” But despite the misery I gave them they said, “No, keep at it, keep at it, you’ll be all right.” “I want to come home.” “No no, stay at it, stay at it.” That went on for I suppose about three or four months.

They must have been miserable themselves.

Awful for them. Awful. I always remember, for that first term of college I stayed in London for the whole three months. Every other term after I think I got home for a weekend. I’d take the 54-shilling round-trip from Victoria Station and the United bus would drop me off in Seaham, just to get home and see them.

How long did that take?

It left at something like nine o’clock at night and dropped me off at Seaham at six o’clock in the morning. Quite long in those days with incomplete roads. And then having to have Sunday lunch and get back on the train or the bus, I could feel that homesickness of not wanting to leave again. And that stayed with me quite a long time. It was a very big contrast with living in the little town where I came from. I found it very difficult but slowly as time went by I built up a circle of friends and had a lot of fun and settled down eventually.

And eventually you settled into opera as opposed to your intended course.

It didn’t take long, really. In my last year in college I was studying with James Lockhart, who had then just been appointed. He was a coaching conductor here. And so we worked here. We worked in one of the buildings across the way on various things. He used to take me through various scores and show me how to mark them up. And then he asked me to audition for Welsh National of which he had just become music director, and I did and I got an understudy and they gave me a small role, and I went to Glyndebourne to get some more experience onstage, and they offered me all kinds of things, just to tease me a little bit, a Christie Award and things like that.

What do you mean, tease you?

Well, temptations to come back to Glyndebourne. It was the Christie Award but there was an awful lot of singing in the chorus that had to be done. I had done that once and I wasn’t mad to go back down that route. And then Welsh National at the same time offered me a contract and I had this dilemma which seemed huge at the time. I went to Welsh National and basically learnt my trade.

Why was it a dilemma?

It was mainly because you felt, if I say no to them they will never come back to me. And if I say no to them, they’ll never come back to me. So it was either go to Glyndebourne and throw away the opportunity with Welsh National or go to Welsh National and never see Glyndebourne.

Why did you choose the WNO?

I think they plied me with drink.

And bigger roles?

Not initially, but there was an opportunity certainly of some interesting stuff. And the possibility of really learning the standard repertoire, things like Bohème and a role that I grew into in Boccanegra. And then Magic Flute came up not very long after that and The Barber of Seville came up almost immediately. Figaro in The Barber - I would never have had that opportunity elsewhere. I think in the end you come via a circuitous route to the same meeting point. I chose to go that route and it was great, it was a wonderful three years.

Below: Sir Thomas Allen as Don Alfonso in Così Fan Tutte, 2004 © Bill Cooper/Royal Opera House

And then you came here.

And then you came here.

The football scouts were out and kept an eye on me and then I came here. About ’72, that was. And was a remnant of the post-war company that still existed really.

You spent the best part of the 1970s as a staffer. You were contracted to the Royal Opera House. Did you sing much elsewhere or were you tied by the apron strings?

Not a lot. ’72, which is when I think I joined here, was a year when I did quite a lot of my first concerts abroad in Portugal and Italy and Spain so there was a lot of that going on in my life. Suddenly it started. And what it meant though, more and more as time went on, was the fact that you were being refused because the company wanted you here for this small role or slightly bigger role, whatever it might. But I had this offer to go and do that. "Can’t do it. I’ve got to be here. I’ve got this pile of invitations and this contract here. This seems to indicate that I might have the possibility of a freelance career." So I looked at the pile of invitations that I hadn’t been able to accept and thought, it’s a gamble. It was about five seasons I did here as a company member.

Do you have a memory in that period of playing roles which provide you with a showcase?

It was slow. It was slow because there were others who had to be accommodated. Whilst in ’77 I sang Don Giovanni at Glyndebourne for the first time and again in ’82, it wasn’t until after that that I was invited to sing it here. Early on in my career in Wales I sang the Count in Figaro and it wasn’t until I think ’79 that I sang it here.

In the end it was partly about standing in the queue.

Yeah. And you have to be tough. I wasn’t sure that I was tough enough. In ’76 I also had hepatitis which knocked me back for a good few months. There was a stage when I never thought I’d actually get back. I thought I was on the way out: it was bad. And I had to fight my own corner. There were those that weren’t greatly in favour of me, that didn’t see what potential I might have or if there was any special talent there.

Who would they have been?

I’m not sure I’m prepared to say. It probably could be easily surmised when you think of the company at the time. I just had to fight my corner, as I say. But Pelléas was important to me in this theatre, and Faust. There was a production of Faust which got off to a very shaky start. It was Kiri [Te Kanawa] was maybe feeling a little bit over-parted [sic] by it, Stuart Burrows who was wonderful but it perhaps wasn’t an ideal role for him, and it was all really revolving around Norman Treigle, the American bass coming to sing Faust. It just didn't gel. But the second time around when we had Mirella Freni, Alfredo Kraus and Nicolai Ghiaurov and myself still in it, you were in a different league. It was grand opera at its grandest with great great singers and it was really extraordinary. They just took the bull by the horns. That was certainly a moment in my life where I thought, well I either sink or swim tonight. I’d better start getting out there and working. And it worked. It was one of those moments where I took a step up the ladder. And Pelléas was as well.

How early on did you realise, or have it pointed out to you that quite apart from your ability as a singer you had this great facility as an actor?

I don't know where that came from. There were one or two colleagues that I had because I was watching and observing and trying to build up and learn a technique, knowing how to cross a stage and not fall over your feet and what your body conveys – whilst I was doing all of that and learning it from other people, I suppose it developed, and I realised what interested me most was not being a canary but in being one of those music theatre animals. By choice I go to the theatre and for work I come to the opera. And I’ve always for a long time been intrigued in this process of trying to marry words and music and the body and finding a way of amalgamating all of that so that you get some kind of credible dramatic context.

I am very aware that certain playwrights have no time for opera. They consider it an absolute nonsense. And I can see that at times that it can be, because there’s no reason at all why it should work. And yet if the chemistry is right, and it does involve getting people together of like mind, who have this similar balance about what they can do, what they can portray in a particular character, in a particular role in marrying that to their voices, then you can get into some very wonderful areas. And occasionally, very occasionally, that happens.

You are returning next year in a production of Il Turco in Italia, presumably because that is the kind of thing you are talking about.

It’s an unusual choice but you’re right. Alessandro Corbelli whom I admire greatly – I think he’s a tremendous artist – comes from that line that goes a long way back. For me my memories of working with Sesto Bruscantini are very important. And Alessandro is like that. He comes from that same line of very intelligent application to the work. And when you’re working together as we will next year on that piece, it’s great fun. You discover all kinds of things. You play with text. You play with one another.

Below: Sir Thomas Allen as Prosdocimo in Il Turco in Italia, 2005 © Catherine Ashmore/Royal Opera House

How satisfying for you is it as a singing actor to get an audience to laugh?

How satisfying for you is it as a singing actor to get an audience to laugh?

It’s amazing. The whole mechanics of comedy and how it works – I’m very aware of seeing a show and the timing being slightly out. You have to understand the mechanics of a gag, whatever it might be. I mean, we’re not in the business of just doing gags but there are gags there and you have to know how to play them. And so often they just go by and you’ve missed the opportunity. But when you’re working together with someone who understands all that it’s immensely satisfying to have some connection in that sort of way.

How much have you learnt from theatre as an actor? Have you used it as an education tool?

Oh yeah. I think so. I understand people. When I’m talking about people that I encounter in my life privately or whatever it might be, I think theatre and the whole business of trying to understand the psychology of a character has aided me enormously in life in general. I think I have learnt a great deal from it. In that way it’s been a university. It’s been a training in understanding human psyche. That’s the other aspect of what we’re trying to do. Sitting down in the canteen or the lounge or rehearsal room or wherever it might be and try to fathom why so and so behaves in the way that they do, why they say the things they do. And it’s a fascinating process. I think sometimes it’s not possible to arrive at a real conclusion and a valid answer. It’s rather like doing crosswords. The clues vary considerably in their quality. And similarly I think some of the arguments that we have to take up in putting on an opera vary too. You may not have that lucid examination of a person that will give you the answers at the end of it all. But in the best of circumstances I think you do find that. And in the process you learn a lot.

For example The Meistersinger which we did here a few years ago was an enormous undertaking, and again involved a lot of people who were of like mind, so we knew we were onto something special, there’s no doubt about that. And I couldn’t for a while get to grips with the role I was playing. I knew the kind of man he must be or should be. Except I thought I understood it all. I just couldn’t get to grips with it. I looked at the way a council is constituted. I used to sit as chairman as something called the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents. We used to sit in the council chamber guided by local councillors and we were learning how these things work. When I came to do Meistersinger I remember thinking about Fred Alderson in Seaham, who was the learned trained scribe sitting alongside the chairman taking down notes, advising, giving all of that sound advice. Beckmesser was like that, I found. Beckmesser was the Fred Alderson who sat there. He wasn’t the leader but he would give advice and commentary and criticism. And so it suddenly started to fit into a life that I knew and then it was a really interesting journey I took on for myself, to see the nature of someone like that.

And Gianni Schicchi. There’s so little that we know as to why he behaves towards this family the way he does. It’s those things that make it interesting. Trying to write the prequel so you know where you arrive at when you actually come onto that stage for the first time.

What do you require from your director?

I was talking about this with a young singer in the chorus this morning when we were sitting in the wings. There was a time when the Wall was still up that we entertained a lot of East German directors over here and they did tremendous work, big works. But they came - people like [Joachim] Herz and Harry Kupfer – with this Gesamtkunstwerk concept, and you knew that they’d lived with this particular piece or the other for many many years, and if you were to step into that and make a contribution, it would be rather like my stepping into David Hockney’s studio and flinging some paint over a major picture that he was doing. I had no contribution to make, that was their opinion. I thought that was a very very sterile piece of ground to be ploughing because it disallows the artist to actually bring anything of their own. You’re there purely as a piece of grey material that the director will then mould to his or her satisfaction, and I don’t like that relationship. I think that we have accumulated over whatever period of time great skills and it’s rather foolish of a director to overlook that aspect of things and have this one concept of the piece and try to shoehorn the people into it, whether they are suited to it or not.

I much prefer the other approach, which Peter Hall for example has always had, in looking at the strengths and weaknesses that an artist has and then allowing there to be a possibility to mould the production to that person or mould them around it or fit them into it, but always have that ability to adapt in some sort of way. The other method is really stifling and I have had difficulty with that in one or two occasions.

You’re prepared to say so in the rehearsal room?

Yes. Maybe I’m considered difficult. I don’t think I am. I’d like to think that I have some kind of nous and could get from A to B, and maybe I’ve just fortunate in not working with too many directors that did dictate in that kind of way. I mean the hardest and most difficult person I ever worked with was Giorgio Strehler at La Scala doing a new production of Don Giovanni when Giorgio was then 66. And the man is gone now, and not to be cruel, but I think his best days – and those best days were extraordinary, the things that he did, no question of that – but they were largely behind him. But nevertheless we had this Giovanni to do, which had an enormous set, a huge set by [Ezio] Frigerio, and he knew what he wanted. They looked from one seat in the centre of the theatre and he was insistent on balancing the characters up and knowing where they were on a particular stage, the elegance with which I dealt with Zerlina, all of these things. But it was negotiable. I mean that was the nice thing about it. Negotiable by screaming at one another at times. It was an interesting process but bloody hard. I’ve never worked so hard in my life. And then Mr Muti came in and said, “You’re all too far back, come to the front.” And you created a sort of concert situation. But that’s the norm for the way he works. But it’s anathema as far as I’m concerned.

Have your relationships with directors in this building been as important as with conductors?

I would say so, undoubtedly. Early days, working with John Copley, I learnt a huge amount from him. I did his Bohème in 1974. He has huge stores of knowledge still to give young artists. Things that they should know. He’s a store of information on, for example, the language of a fan, how to use a fan, how Madame Butterfly uses a fan, how Rosalinda in Fledermaus uses a fan. That’s knowledge that I have a great fear could easily slip down the drain and be gone from us forever. He’s a kind of treasure box of all of that kind of stuff that you can tap into and I think it’s important that people should whilst he’s around. I try to do a little bit of that because I think it’s passing on extraordinary knowledge.

Below: Thomas Allen as Marcello in La Bohème, 1984. Photograph from Donald Southern Collection at ROH Collections

Presumably you don’t encounter people who don't want to hear what you yourself have to pass on.

Presumably you don’t encounter people who don't want to hear what you yourself have to pass on.

I don’t think so. It’s a healthier community generally than that. There have been others. Last year we had a wonderful time, wonderful atmosphere putting on Hänsel und Gretel. It was just wonderful, an amazing experience. I love working with Moishe Leiser and Patrice Caurier. They get on with the work. They are smiling when you walk into the rehearsal room in the morning, create an atmosphere in which you love to work. There is no Sturm und Drang. I’m sure they lose their rag over things occasionally but generally they create an atmosphere in which you become very productive. And why not? It doesn’t need to be aggressive and at times it has been so. The stamping of feet has been heard.

I’ve asked actors many times but never an opera singer how it is to be directed by Woody Allen, as you were in Gianni Schicchi last year in Los Angeles.

What do I say to that? Let me ask you a question. What do the actors answer to that?

It’s always the same thing. They go to his apartment on the Upper East Side, they don’t have to read or anything, he looks at them and says "Hi", asks them a couple of questions and then says, “OK, you’ll be hearing from us.” The transaction is drained of personal charisma or any sense of curiosity about who they are. There is no emotional contract between director and actors.

I’d agree with that. It’s difficult to say because I never got to know the man. I was with him for a month and I went away from here saying to a colleague of mine, “It’ll be great.” He said, “You’ll never get to know him.” I said, “No, nonsense, we’re there for a month and I’m sure we’ll have dinner together some time, there’ll be discussions about things, it’ll be highly entertaining. I’m looking forward to it very much.” None of the above. None of the above. The jury is not out in that one. I really don’t know what makes him tick.

Did you feel that you were you being capably directed, that he knew what he was doing in this unfamiliar art form?

The impression I got was that he was looking at a storybook as though for a film. It was almost as if he were saying, “I like that picture over there. Can you make that group again?” And that was the gist of it. It was a quite different experience from anything I had done before. No, it was underwhelming. I wanted to hear the fount of something, whatever he’s the repository of, and the words coming from the mouth. I just didn't get them. It’s one of those occasions when a cast look at one another and go, “Well, we’d better look to our laurels here and make this work.” It’s often the case and I know this because I’ve directed opera myself, you make a decision as to who is going to design the opera for you, or you inherit one that’s already designed. I’ve been in a position of having chosen a designer and I realise how much work is done by that person, how many decisions are then made. I mean you discuss it jointly in the lead-up, but a huge amount of work is dealt with in that process of the doors, the windows, the geography that you’re provided with. And that answers in many ways a lot of the questions.

What took you into directing?

Someone said, “You really ought to.” Why? Occasionally people say, “When are you going to take up conducting? You’ll be doing that next.” That happens to a lot of singers at a certain stage in life. And you think, I’ve no qualifications, no one’s ever taught me how to do that and I’m not trained to do that. I mean, it would fun to do that and hear the noise that it makes, but I’m not going to have 100 angry musicians playing out of tune for me or playing a semitone up and wondering if I’ll ever realise that it’s in a different key. All of these tricks are played. No interest to go there. Neil Mackie at the Royal College of Music said to me quite a lot of years ago, “If you ever decide to direct, can we have you first here?” And an American gentleman, Joel Revsen [of Arizona Opera], said to me, “I’d love you to do something. If you’d like to direct, what would it be?” And I always said to both of them, “I’d love to have a crack at Albert Herring.”

Below: Sir Thomas Allen as Gianni Schicchi, 2009 © Johan Persson/Royal Opera House

Why?

Why?

I could have said Gianni Schicchi which is shorter but I wasn’t quite so familiar with Gianni Schicchi then. Albert Herring I had a relative early acquaintance with in 1974 in wonderfully happy circumstances at Aldeburgh, and the cast was well chosen, they were all very very suited to their roles and we had a lovely time doing it. I’ve often thought that you can play and play and play with this piece. It’s such a wonderful observation of this little village society with the grande dame at the centre, the policeman and the mayor and the grocer and the schoolteacher. It’s a tremendous little slice of life and I just wanted to play with that.

Does it remind you of home at all?

Oh yeah, yeah. It’s like being a writer, you just write about the things you know about. Different part of the coastline but it could have been up there. We don’t have the grandes dames that they have in East Anglia in quite the same way. But it may well have been to do with all of that. I recognise all of the different levels.

When was that first production?

Getting on for 10 years ago.

How much directing have you done since?

I’ve actually done the three Da Pontes, properly, fully staged - costumes, the whole lot – in Arizona. I’ve done Figaro there at Arizona Opera. Così and Don Giovanni I’ve done at the Sage with our foundation Samling.

How did the foundation come about?

It started about 14 years ago. I was in the North-East doing a concert and a young lady was waiting to speak to me after the rehearsal. She said, "I’ve come as a representative of Roger McKechnie, and he’d very much like to set up masterclasses at a place he’s got in the Lake District.” I said, “That’s very interesting. It just so happens that I’m getting to the stage in my life that it would be lovely to come back home and put some muck back in the soil, as it were, and see what happens.” This was late on the year. By the following spring Roger’s place on Windermere had been developed and we started and it’s gone on now for 14 years and we’ve taken small group of singers by audition, almost as many and sometimes more teaching staff, grizzlies like myself, pianists, actors, and grilled them for a week in a location and made them aware of the level of achievement they’ve got to aim for.

How old are they?

It varies considerably. Some are quite young, 22, 23 - they’re all certainly well trained and advanced in the skills that they have - and sometimes into the thirties.

Do you go every year?

I go as often as I can. Sometimes work keeps me from it, but basically yes. But it’s been wonderful to watch this thing grow and to see the increasing respect and its reputation around the world now.

Out of that programme have you produced a young lyric baritone?

Well, we see them for a week in their lives so we can’t take full credit.

It’s another way of saying, who are the lyric baritones? Is there anyone you would anoint as your successor?

Jacques Imbrailo is making a name for himself. He’ll be singing Billy Budd at Glyndebourne next year. There’s a lad that’s just graduated from the Guildhall called Gary Griffith who I think is very very promising. Lukas Karl is an Austrian baritone. There is a lad called Philip Smith who I’m keeping an eye on, who is from Yorkshire. I heard something in his voice that I thought was really most interesting. I think the baritone mantle is in safe hands.

I think we do make a difference. You can be at any number of conservatoires and academies, but when you’re with grizzled professionals and we work on poetry and on Italian, French, Russian, Czech texts, really getting to grips with them and wringing out of them everything we possibly can - we meet at breakfast and you’re there still when you’re having supper at night, for seven days – I think it leaves its mark. That’s what they all say: that it’s been life-changing.

As you get older you have to give up singing certain roles. Which have you found hard to hand on?

Pélleas came back into my life far too recently in Athens of all places. I went there specifically to sing it with Jeanette Pilou who was retiring, with whom I’d sung it many years ago in Argentina. In response to someone saying, “What would you like to do as a farewell performance”, she said "Mélisande with Tom." So I went there and did that and it was wonderful. We did look as if we should be in our bath chairs a little bit. Giovanni is the hardest one I’ve given up. Billy Budd I knew would have to go, and Eugene Onegin. Giovanni, my feeling is always there is a power in the man that’s never going to die, whatever age he is. That fire is still there. And I’ve always been curious as to how it works later and I haven’t sung it for quite a lot of years now.

Did you know it was the last time?

No, it just didn't appear again. It cropped up once in Munich because I have a long association with them. There’s a new production coming in Munich but realistically I won’t be singing it. It doesn’t stick in the craw but it just leaves me feeling curious about that aspect of that little corner as to how it would be. When I did it in Munich, I’d not sung it then for quite some years and of course the policemen get to look younger and smaller and a new generation of young singers had come along, and quite a number of them in the cast had no idea who I was. Singers are very uncurious as well at times. So there I was onstage doing my favourite bits of the text and a young lady, I think it was the young Zerlina, said, “I’ve never heard anybody do it quite like that. You do things differently.” I said, “Just imagination. Just use your imagination.” And I think it is an interesting exercise to introduce someone rather like a dinosaur, to be absolutely crude, and see how they survive. I think it can create quite a stir.

If you had a gala night at the Opera House and they say, “You can sing one role,” what would you take? It’s another way of asking what has been the untoppable highlight of your career in this building.

That’s really difficult. That’s really difficult to answer.

Do you want to have five then?

Giovanni would have to be one of them. I think Onegin would have to be one of them although he’s not there half the time. There are some performances that really registered with me, particularly with Ileana [Cotrubaş]. I didn’t sing it here that much. Beckmesser undoubtedly. And I think the last one would be the one that just went, Gianni Schicchi which came only last year into my life and thank God it did. I did it last year in Los Angeles.

Below: Sir Thomas Allen as Gianni Schicchi, 2009 © Johan Persson/Royal Opera House

Are there any roles you would have been quite happy not to have sung?

Are there any roles you would have been quite happy not to have sung?

Oh, yeah. Belcore in L’Elisir. I’m not a great Donizettian at the best of times and I wasn’t good. I just wasn’t good. I didn't get that one.

The Sweeney Todd production here was not garlanded with flowers.

No, I gathered that. Not that I read criticism, but I gather that.

Undeserved?

Yeah, I think probably. I’ve no way of judging these things. I don’t know what they said about it that they didn’t like it. We worked bloody hard on the stage to make it work, I know. I think the production itself came in for a lot of criticism. But it’s a different kettle of fish. It then went on in a reduced skeletal version in the Whitehall Theatre or something at the time.

With the actors playing all the instruments.

Well, it’s not to be compared with a show of that sort. That’s a completely different way of dealing with it and we weren’t going to be doing that in any circumstances. This was a show that came from Chicago anyhow. And I was happy to do it. It’s a mammoth piece and I’d done some Sondheim before that, which was very very trivial by comparison – A Little Night Music – and so it was an enormous mountain to climb really, and a killer of a piece. But Felicity [Palmer] was wonderful in it and there were some really great performances, I thought. We did what we could. If people didn’t like it, well I don't know: we did what we could.

You mentioned Donizetti. You’ve covered a vast range from Monteverdi up to the MGM musicals at the Proms this summer and beyond into Sondheim. Has there ever been a moment where you’ve thought, actually I shouldn’t be singing this?

Yeah, there was a record I made some years ago. It was show tunes and it had to include a bit of Phantom of the Opera, and I couldn't get any joy out of that, I’m afraid.

Have you had to work harder on areas of your voice? Has the whole package remained in shape?

Yeah, basically. Hasn’t changed. I think I study scores differently now. Probably because I’m aware that much against my better judgement of earlier years it would appear that time is finite, that the time of doing these things does have a closing date. God knows when that’s going to be. I’m enjoying it for the moment. You’ll read criticisms that I don’t. I hear about them in newspapers – “Of course the voice is not what it used to be blah blah blah” – these ageist remarks. Well frankly my voice really hasn’t changed at all. I’m sure there are moments when you think that little glitch there is a sign of age. As far as I can hear and as far as I can feel, and I think I’m pretty close to the subject, nothing much has changed. When I listen to old recordings there was a way of attacking phrases that was very virile and that was the natural way to do it then. You do it maybe slightly more cushioned now, looking after yourself and husbanding resources. But I’m prepared to expend a lot of energy on that stage. I still have a lot of energy and I think I still have quite a bit of voice to give. I don’t see any different.

If you had gone into medicine you’d have been retired. Do you have any thoughts of eventually not singing?

No. I think if you let that worm in it eats away at you. It’s not the way I would have planned it. I mean certainly at some point in my life I was thinking I’ll take a semester there. You can’t take semesters in this business. You can’t say, “I’ll do a month there and go to the Caribbean for three months and come back and do another month’s work.” You either commit yourself to this work, and do it properly and wholeheartedly, or you decide the time has come, I must now leave it. You can’t dip into it occasionally. That’s when the voice does show signs of age. It just takes that much longer to get the machine going. So I’m just keeping going. At one time I would have said I’d have been out of here by 60. I’d be painting or birdwatching, the pursuits that I enjoy more, and enjoy family. You make a big sacrifice in missing out on an awful lot of family over the years, and I’ve done that. So catch up that time. It’s not time yet. I’ve realised in recent years I actually quite enjoy doing this, much to my surprise.

Only recently?

It was something I could do but I always tried to play down the importance of the relevance of it in my life. Maybe that was my way of taking off the pressure because I’ve never stopped working. I mean I’ve been doing it solidly. There haven’t been great gaps in my life. Just one job after another for 41 years. And so I think my way of dealing with that mentally was to say, “Well, it’s not that important; just go on to the next one and I can take it or leave it.” If it became a big issue in my life I think I’d have gone into an early grave or an asylum. It’s very demanding. But that way I steered clear of problems where there might have been some.

You described the gesture that you might have made to the Royal Opera House had they offered you a small role in Der Rosenkavalier 20 years ago. What happened when the offer was finally made?

I was ready to not make the gesture. Well, why not? Seemed like a good idea at the time. And this word “challenge” seems to crop up in my life a lot. It was a nice challenge for me as well, to make sure that I could still know how to open a score and start studying it and get it into my head. It’s a constant reminder too that you’re still able to do that.

There aren’t many roles left for you to learn though.

I have to learn one for a film next year but I think I’m going to draw a curtain over that. That’s it.

Last question. Could you sum up what this building has meant to you?

Well, first of all, this is not a sour note but it is a note that one has to state. Once it’s gone it’s gone. It’s no good thinking that you’ll be remembered for time immemorial. You pass your time here and then it’s over. And that happens to everybody great and small. But what it does have for me - and singers have this tremendous ability for lapsing into nostalgia – is I find myself understandably going in that direction every now and then, thinking, "That was a nice memory." Because there were some amazing memories. The place is full of ghosts. Some of them are just hanging on to life. There’s one I can think of who is 83. John Vickers who was this astonishingly strong tenor who had nerves of steel and a voice like steel as well is riddled with Alzheimer’s. It’s just sad. I go back and I can see them all. David Ward, John Lanigan and Forbes Robinson and Joan Sutherland and whole hosts of people that were associated with this building. And that was that generation before mine and I got in on the tail-end of that and listened to their tales and their memories and it was wonderful, absolutely wonderful. Great great people. To think that I sang here in the early days with Sena Jurinac and I sang here with Boris Christoff. These were major major names. And Alfredo Kraus and Nicolai Ghiaurov, no longer with us. I sang with those people. And that’s not bad really.

Well, first of all, this is not a sour note but it is a note that one has to state. Once it’s gone it’s gone. It’s no good thinking that you’ll be remembered for time immemorial. You pass your time here and then it’s over. And that happens to everybody great and small. But what it does have for me - and singers have this tremendous ability for lapsing into nostalgia – is I find myself understandably going in that direction every now and then, thinking, "That was a nice memory." Because there were some amazing memories. The place is full of ghosts. Some of them are just hanging on to life. There’s one I can think of who is 83. John Vickers who was this astonishingly strong tenor who had nerves of steel and a voice like steel as well is riddled with Alzheimer’s. It’s just sad. I go back and I can see them all. David Ward, John Lanigan and Forbes Robinson and Joan Sutherland and whole hosts of people that were associated with this building. And that was that generation before mine and I got in on the tail-end of that and listened to their tales and their memories and it was wonderful, absolutely wonderful. Great great people. To think that I sang here in the early days with Sena Jurinac and I sang here with Boris Christoff. These were major major names. And Alfredo Kraus and Nicolai Ghiaurov, no longer with us. I sang with those people. And that’s not bad really.

Some people will be saying the same of you one day.

If they haven’t forgotten me altogether. We make a mark for the time that we’re here and then it’s time to move on and do some painting.

You’re not going anywhere, though.

No, not for the time being.

Thank you very much indeed.

Not at all.

I didn't ask you about your knighthood.

Oh, I’ve nothing to say about that. It’s very nice.

What happens when people call you Sir Thomas? Do you ask them not to?

It depends on the person. There are those I think that should. I put them through that agony. And there are others where I say, “Oh, don’t say that, it makes me feel so old.” But I don’t deny it’s there and I’m honoured to have it. I’m not a hugely royalist person but my country for one reason or another chose to give me this thing and similarly in Germany they made me a Kammersänger. It’s wonderful. You sing a lot of notes for a long time and people recognise the fact.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Dangerous Matter, RNCM, Manchester review - opera meets science in an 18th century tale

Big doses of history and didaction are injected into 50 minutes of music theatre

Dangerous Matter, RNCM, Manchester review - opera meets science in an 18th century tale

Big doses of history and didaction are injected into 50 minutes of music theatre

Mazeppa, Grange Park Opera review - a gripping reassessment

Unbalanced drama with a powerful core, uninhibitedly staged

Mazeppa, Grange Park Opera review - a gripping reassessment

Unbalanced drama with a powerful core, uninhibitedly staged

Saul, Glyndebourne review - playful, visually ravishing descent into darkness

Ten years after it first opened Barrie Kosky's production still packs a hefty punch

Saul, Glyndebourne review - playful, visually ravishing descent into darkness

Ten years after it first opened Barrie Kosky's production still packs a hefty punch

Così fan tutte, Nevill Holt Festival/Opera North review - re-writing the script

Real feeling turns the tables on stage artifice in Mozart that charms, and moves

Così fan tutte, Nevill Holt Festival/Opera North review - re-writing the script

Real feeling turns the tables on stage artifice in Mozart that charms, and moves

La Straniera, Chelsea Opera Group, Barlow, Cadogan Hall review - diva power saves minor Bellini

Australian soprano Helena Dix is honoured by fine fellow singers, but not her conductor

La Straniera, Chelsea Opera Group, Barlow, Cadogan Hall review - diva power saves minor Bellini

Australian soprano Helena Dix is honoured by fine fellow singers, but not her conductor

The Queen of Spades, Garsington Opera review - sonorous gliding over a heart of darkness

Striking design and clear concept, but the intensity within comes and goes

The Queen of Spades, Garsington Opera review - sonorous gliding over a heart of darkness

Striking design and clear concept, but the intensity within comes and goes

The Flying Dutchman, Opera Holland Park review - into the storm of dreams

A well-skippered Wagnerian voyage between fantasy and realism

The Flying Dutchman, Opera Holland Park review - into the storm of dreams

A well-skippered Wagnerian voyage between fantasy and realism

Il Trittico, Opéra de Paris review - reordered Puccini works for a phenomenal singing actor

Asmik Grigorian takes all three soprano leads in a near-perfect ensemble

Il Trittico, Opéra de Paris review - reordered Puccini works for a phenomenal singing actor

Asmik Grigorian takes all three soprano leads in a near-perfect ensemble

Faust, Royal Opera review - pure theatre in this solid revival

A Faust that smuggles its damnation under theatrical spectacle and excess

Faust, Royal Opera review - pure theatre in this solid revival

A Faust that smuggles its damnation under theatrical spectacle and excess

Comments

...

...