10 Questions for James Marsh | reviews, news & interviews

10 Questions for James Marsh

10 Questions for James Marsh

The director of Shadow Dancer on walking the high wire between fact and fiction

Five years ago James Marsh won an Academy Award for the documentary Man on Wire. It thrillingly told the story of Philippe Petit’s audacious walk on a tightrope between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in 1974. Marsh stayed on in the 1970s for Project Nim, a chilling documentary about a hubristic American scientist who as an experiment tried to bring up a chimpanzee as a human.

Shadow Dancer, critically acclaimed on its release and now out on DVD, is adapted from the 1998 thriller of the same name by the ITN reporter and novelist Tom Bradby, who was based in Belfast in the bloody preamble to the Peace Process. The all too plausible plot concerns a female republican terrorist (Andrea Riseborough) who, when captured, is offered an impossible choice by her male MI5 handler (Clive Owen): to become a British mole or go to prison and lose contact with her young son.

I don't know anything about actors

Marsh is not an entire stranger to fiction on film, nor to the pitiless drab council estates summoned in Shadow Dancer (Belfast was, whisper it softly, actually played by Dublin). For Channel 4 he filmed one third of the Red Riding trilogy based on David Peace’s novels about the hunt for the Yorkshire Ripper. But his background is very much in factual. Born in 1963 and brought up in Cornwall, in his twenties he cut his teeth on the BBC’s flagship documentary strand Arena. He talks to theartsdesk about the transition from fact to fiction.

JASPER REES: Can you recall your first encounter with the film script for Shadow Dancer?

JASPER REES: Can you recall your first encounter with the film script for Shadow Dancer?

JAMES MARSH: I was sent a script cold from my agent and when I realised it was about Northern Ireland and the Troubles I almost didn’t bother to read it. I wasn’t sure we needed any more films about that part of our recent history. We’re pleased that it feels like it’s over in its most horrible form and good riddance, but I got increasingly intrigued by the central idea: what would it be like to be given this impossible bargain - either never see your son again and be in jail or betray everything you believe in and spy on your own family? It felt like a universal idea, not just about the Troubles but the whole notion of treason and betrayal of your family, which is about as a bad as it gets. I felt we could do something that was universal and classical not just parochial. It’s such an interesting part of our history. My first response was wrong. You can find all kinds of fascinating stories and maybe now sufficiently into the Peace Process we can look back and mix them for their dramatic possibilities and rather then get caught up in making judgements.

How was it to work with actors on a feature film for the first time?

In a documentary you’re creating a story out of these first-person testimonies and each contributes to the whole, but if you’re editing a feature film you can shape a performance given when you’re shot. I like giving actors freedom. The only thing I do is cast them correctly. Then I sort of keep out of their way and give them the freedom to offer me what they want to do. It’s saying “I trust you. That’s why I’m casting you.” I don’t tend to micro-manage what they do. I’m not an actor. I don't know anything about actors. I’m hiring actors that I think are truly great. My job is to give them good circumstances and creative comfort and freedom. Most good actor really respond to that.

I don't know anything about actors. What you do know about is behaviour. Often my documentaries are about really quite eccentric and extreme behaviour. You bring that to bear to your characterisations in a screenplay. That helps you talk to an actor about it. I’ve never acted, I’ve no desire to be in front of the camera. And I’m respecting the talent and instincts of the actor to do what they want to do. If it feels wildly wrong I would intervene but that’s never happened. Behaviour is what I think I know.

I don't know anything about actors. What you do know about is behaviour. Often my documentaries are about really quite eccentric and extreme behaviour. You bring that to bear to your characterisations in a screenplay. That helps you talk to an actor about it. I’ve never acted, I’ve no desire to be in front of the camera. And I’m respecting the talent and instincts of the actor to do what they want to do. If it feels wildly wrong I would intervene but that’s never happened. Behaviour is what I think I know.

At the heart of the film’s dramatic impact is the performance of Andrea Riseborough (pictured above right). How did you alight on her for the role of Colette?

Clearly when you’re casting around for the most exciting interesting actors she was top of the list. I desperately wanted her to do it. She’s a very good actress but she also has enormous emotional sympathy. What she gave me was a gift of a performance. There’s not a ton of dialogue in the film. So much relies on understanding her emotional condition and she gives you that in a very discreet way. She is wise well beyond her years as good actors tend to be.

It’s a lower budget than Clive Owen (pictured left) is used to. Did he need much persuasion?

It’s a lower budget than Clive Owen (pictured left) is used to. Did he need much persuasion?

He was the first person I thought of. Firstly he’s an iconic actor. He’s a really strong presence physically. Also he’s a really good actor. I think he relished the chance of doing an ensemble film in a smaller cast. He’s a very decent collaborator. He’s a movie star and has been in some very big films but came to this in the right spirit. I think it’s a really subtle and nuanced and vulnerable performance. It makes the film take on quite tragic dimension because the performance is so strong. It is a thriller that ends in a shocking way.

The film is, not unusually, an adaptation of a thriller. The unconventional aspect of its genesis is that the author Tom Bradby was a reporter in the Northern Ireland during the Troubles, and his research was therefore all journalism. Was it important to retain those grittiness of the source material?

Tom was there on the ground. The details of the script and book came from his first-hand experience That makes the whole script very authentic. I’m as interested in the psychology, as the political details of the situation didn't interest me in the same way. What did interest me was the notion of the prize being the Peace Process. The overall objective is to somehow advance a dialogue in the most cynical fashion. I read quite a lot of stuff about contemporary Northern Irish history and politics and began to get intrigued by the way we bullied and oppressed the country for centuries. None of that ends up in the film. But I didn’t want to obsess on the period details. I attempt to transcend the politics and make a pure thriller based on these unusual circumstances.

To put it very glibly, Man on Wire (pictured above, Philippe Petit) is about a man who turns himself into a kind of monkey; Project Nim is about man trying to turn a monkey into a kind of human. Do you have a sense of where Shadow Dancer fits in your canon of films?

To put it very glibly, Man on Wire (pictured above, Philippe Petit) is about a man who turns himself into a kind of monkey; Project Nim is about man trying to turn a monkey into a kind of human. Do you have a sense of where Shadow Dancer fits in your canon of films?

I don't really ponder those things myself. I don’t regard or have any overview about my body of work. You just find stories that you want to tell and find them in all kinds of areas. They can be documentary stories. My rule is I tend to be drawn by films that are truly unbelievable. You have to tell them as non-fiction because they are so preposterous that that’s the way to respond to them. With Shadow Dancer it was this great universal story. To ponder the answer more carefully, one aspect of Project Nim and Man on Wire, they are very much about dysfunctional families and so is Shadow Dancer. That would be a theme that seems to be quite consistent. That’s where you find the most intense relationships and therefore the most intense possibility for drama. They are set in the world of a family and how that dynamic works out. Shadow Dancer is rooted in a reality; it is based on an archetypal story that definitely happened. Those circumstances in Northern Ireland allowed that to happen. But I really don't ponder my corpus. I don’t want to analyse what I do. When I find a story that I want to tell I’m going to do my best to tell it. I submit myself to the story. I don’t have an off-the-peg style. It’s dictated by the requirements of the story. Man on Wire is very different from Nim or Shadow Dancer. I’m hiding behind my work.

What difference did the success of Man on Wire make to your career?

What difference did the success of Man on Wire make to your career?

It felt like it became part of the culture in the year it was released - part of the zeitgeist perhaps. It made a big difference to me in terms of being able to make films more promptly. You become impoverished in the mean time.

The path from television documentary to feature films is not so commonly trodden. Could you explain where you started?

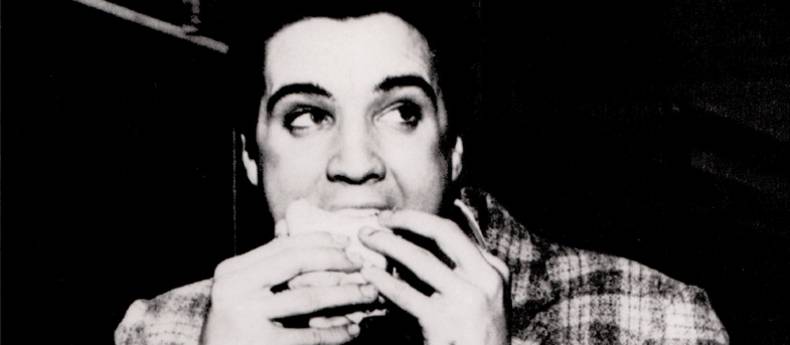

The professional start and the ambition to be a filmmaker are quite different. Professionally I worked at LWT as a researcher on a local arts programme in late Eighties. I went to the BBC and began working on Arena. That was a great place to work. The great joy of working on it was you could come up with any idea however strange it might be and get a hearing. Anthony Wall and Nigel Finch were very important in my career. The first Arena film I made was The Trials of Animals which will show you how eclectic their brief was: partly in Latin, it was a half-hour drama documentary about the curious practice of animals being put on trial in parts of medieval Europe for crimes against person or livestock. It would have a defence lawyer and if found guilty they were executed. The subject was all about our relationship with animals. I worked there for six or seven years making all kinds of quite eclectic documentaries including The Burger and the King (pictured below) in 1994/5 which was sold all over the world. Last Supper about what condemned men request for their last meal in contemporary execution cultures, and what that choice meant. I made a series of films which were about songs inspired by real stories. Troubleman, my favourite Arena film, about the last years of Marvin Gaye and his father. It was shown once and got caught up with legal issues.

It was a great place to work. I wasn’t the only person doing that kind of work. Pawel Pawlikoswski and Mary Harron also worked on Arena and went to the US and made features. We shot on film. There were no rules. As long as you didn’t bore Anthony and Nigel you could get away with anything. It was where I learnt to be a filmmaker essentially. I then moved to the US and was working on projects for British TV which culminated in a film which was a hybrid drama-documentary released in the US. That was the first feature film I made.

It was a great place to work. I wasn’t the only person doing that kind of work. Pawel Pawlikoswski and Mary Harron also worked on Arena and went to the US and made features. We shot on film. There were no rules. As long as you didn’t bore Anthony and Nigel you could get away with anything. It was where I learnt to be a filmmaker essentially. I then moved to the US and was working on projects for British TV which culminated in a film which was a hybrid drama-documentary released in the US. That was the first feature film I made.

What are the significant differences between making a feature-length documentary and a feature-length drama?

The means of production are really quite different and they both have their imperatives. Shooting a feature is much harder than a documentary. You have a much more elongated production period and you can make good on your mistakes if you discover them in time. A feature all happens in a compressed time frame which is quite demanding. The collaboration with actors is different from working and interviewing people in documentaries. But some of the same things apply. But in terms of the storytelling, they have a big overlap. Making documentaries makes you very very focused on structure because often you are trying to deal with unwieldy elements. You tend to get quite good at looking at structure in fiction. The work is almost focussed on editing things down and making it as tight as it can be. Not least you don't want to shoot stuff you’re not going to use. I’m dealing with narrative and storytelling in both mediums.

What are you working on next?

I’ve got one documentary project I’ve been working on for four years and it’s so difficult that I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to do it. It's based on a dream diary I found archived in University of California. This diary was very unusual in that it features only the dreams of the woman he’s fallen in love with. I want to construct a love story based on these dream narratives. It’s a totally preposterous idea and maybe even totally unwatchable but it’s a project I’ve been unable to shake off.

- Shadow Dancer is released on Monday 14 January on DVD and Blu-ray

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

Add comment