The Genius of Marie Curie, BBC Two | reviews, news & interviews

The Genius of Marie Curie, BBC Two

The Genius of Marie Curie, BBC Two

The scientist's life proves too large for an hour-long documentary

Marie Curie must rank right up there among the world’s achievers of greatness. She certainly wasn’t one of those who had it “thrust upon ’em”. In fact, fate stacked the odds against her achieving the eminence she did in just about every way possible.

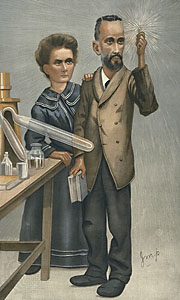

She was born Maria Skłodowska in Warsaw at a time when Poland was dominated by its Russian occupiers, and scientific training for Poles could only be had on the hoof in the underground, so-called “flying” universities. Through great good fortune she followed her sister to the Sorbonne, one of the very few universities accepting women at the time, in 1891. The first woman to win a Nobel prize, for physics in 1903 (a second, for chemistry, followed eight years later), her name was only included in the nomination for that first award at the insistence of her husband and collaborator, Pierre (the Vanity Fair illustration, pictured right, depicted her in a typically subsidiary role).

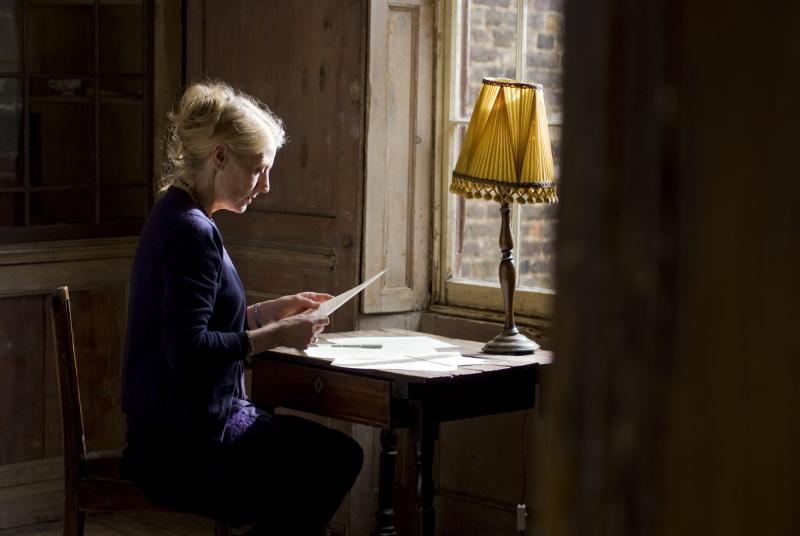

Subtitled “The Woman Who Lit Up the World”, Gideon Bradshaw’s documentary chose an episode from Curie's private life for its moment of crux. Five years after the early death of her husband Pierre in 1906, Marie was having a love affair with the physicist Paul Langevin (Pierre’s former pupil), hoping that he would leave his unhappy marriage for her. Instead, the passionate letters she wrote to him (read in the film by Geraldine James, main picture, above) were leaked to the press through the wiles of Langevin’s wife, and Curie was subjected to trial by tabloid, racially vilified as the “foreign woman” attacking the sanctity of a French family: her house was even attacked by an angry mob. Langevin, put out at accusations that he was “hiding behind a Polish woman’s skirts”, melodramatically challenged a newspaper editor to a duel that passed off without a bang, and then returned to his wife.

Subtitled “The Woman Who Lit Up the World”, Gideon Bradshaw’s documentary chose an episode from Curie's private life for its moment of crux. Five years after the early death of her husband Pierre in 1906, Marie was having a love affair with the physicist Paul Langevin (Pierre’s former pupil), hoping that he would leave his unhappy marriage for her. Instead, the passionate letters she wrote to him (read in the film by Geraldine James, main picture, above) were leaked to the press through the wiles of Langevin’s wife, and Curie was subjected to trial by tabloid, racially vilified as the “foreign woman” attacking the sanctity of a French family: her house was even attacked by an angry mob. Langevin, put out at accusations that he was “hiding behind a Polish woman’s skirts”, melodramatically challenged a newspaper editor to a duel that passed off without a bang, and then returned to his wife.

It was the only real hint at private feelings that we got in the film, a glimpse behind those mesmerisingly sad features (pictured below). Pierre’s marriage proposal, presented here as a silent film inter-title – “it would be a fine thing to pass our lives near each other, hypnotised by our scientific dream” – hardly hinted at passion; Curie, the prototype “modern woman”, was back in her laboratory very soon after she gave birth to her two daughters, passing almost complete care for them to her father-in-law.

Cambridge science historian Patricia Fara gamely led the cast of commentators here – another lady, back on the country estate in Poland where the young Maria had worked as a tutor, had a glorious snowy backdrop behind her straight out of David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago – but Curie finally proved too considerable a figure to condense into an hour of screen time. It wasn't for lack of effort on Bradshaw's part: the director assembled a veritable farrago of visual material, mixing extracts from various screen adaptations of the Curie story with what must have been reconstructions, and some scenes that looked confusingly somewhere between the two. Archive was as full as it was inventively used.

Cambridge science historian Patricia Fara gamely led the cast of commentators here – another lady, back on the country estate in Poland where the young Maria had worked as a tutor, had a glorious snowy backdrop behind her straight out of David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago – but Curie finally proved too considerable a figure to condense into an hour of screen time. It wasn't for lack of effort on Bradshaw's part: the director assembled a veritable farrago of visual material, mixing extracts from various screen adaptations of the Curie story with what must have been reconstructions, and some scenes that looked confusingly somewhere between the two. Archive was as full as it was inventively used.

Musically it was a mélange too, the more usual historical material mixed in with a snatch or two of Edith Piaf, and some contemporary balladic songs in English that melded so well they could have been written specially (one refrain, “I can’t get enough of that stuff”, mixed perfectly with black and white footage of a female figure stirring a cauldron of Curie's favourite research material, pitchblende). It left the impression that the director had considerable fun trying to "light up" his subject, even if Curie’s life here sounded much jollier than its details – as well as that haunting face – would suggest it really was.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

Add comment