theartsdesk Q&A: Kate Lindsey and Katharina Thoma on Glyndebourne's Ariadne auf Naxos | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Kate Lindsey and Katharina Thoma on Glyndebourne's Ariadne auf Naxos

theartsdesk Q&A: Kate Lindsey and Katharina Thoma on Glyndebourne's Ariadne auf Naxos

A director and a 'composer' discuss the riches of Richard Strauss's hybrid opera, opening the Glyndebourne season

What’s the perfect Glyndebourne opera? Mozart, of course, must have first and second places with Le nozze di Figaro – Michael Grandage’s lively production of country-house mayhem is revived again this season – and Così fan tutte. Then comes Amadeus’s greatest admirer, Richard Strauss, and Ariadne auf Naxos - his most experimental collaboration with his then-established house poet for Elektra and Der Rosenkavalier, Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

The life-meets-art drama of a mythic opera seria to be staged in the palatial home of "the richest man in Vienna", whose whims mean that a commedia dell’arte troop must perform simultaneously to liven up the boring bits, fits the world’s number one country-house opera company like a silk glove. Even more so in Katharina Thoma’s production, which has taken note of Glyndebourne’s makeshift function as a refuge for infant evacuees (pictured below) in the Second World War to set both backstage Prologue and supposedly onstage Opera in similar surroundings. The concept may turn out to be more serious than usual. With death obsessing prima donna Ariadne, and a shocking experience still rocking the heroic-tenor god who comes to save her, the context sounds more plausible than a bald resumé might suggest.

There to convince me in Glyndebourne's Red Room on a sunny May morning were Thoma and the American mezzo-soprano playing the adolescent, trousers-role Composer of Ariadne auf Naxos, Kate Lindsey. While we waited for coffees, we talked about the executors of the Strauss estate and their wariness of updatings (infamously, John Cox’s 1920s Glyndebourne update of the pre French revolutionary setting for Strauss’s last opera, Capriccio, meant it was never filmed).

There to convince me in Glyndebourne's Red Room on a sunny May morning were Thoma and the American mezzo-soprano playing the adolescent, trousers-role Composer of Ariadne auf Naxos, Kate Lindsey. While we waited for coffees, we talked about the executors of the Strauss estate and their wariness of updatings (infamously, John Cox’s 1920s Glyndebourne update of the pre French revolutionary setting for Strauss’s last opera, Capriccio, meant it was never filmed).

Thoma told me the estate had asked questions about the wartime setting, bearing in mind the sensitive issue of the composer’s fraught relationship with the Nazis, but were reassured when it was confirmed that no SS officers would come anywhere near the action. That led us to chat about the controversy of the Düsseldorf Tannhäuser, over which first night of which audience members were claiming trauma after seeing it Nazified; cancellation swiftly followed. Then the coffees arrived, and on went the microphone.

DAVID NICE Steeped as you are in Ariadne auf Naxos at Glyndebourne, has it been sheer pleasure? Because you’re also bringing out the darker side.

KATHARINA THOMA It has been a great pleasure, yes, and I’m staying in the house. The atmosphere is incredible and I think we’re really lucky because the cast is nice and the people who are staying in the house right now are really lovely, so it’s a very enjoyable time. As for the feeling we have about this piece, I agree that it is the perfect Glyndebourne piece in more than one respect, in some ways that people might not expect, but it gave us quite a lot of opportunities to show details. We're thinking all the time about the history of Glyndebourne.

Did you decide upon what you wanted to do before you came here, or did you come here first?

Every day for seven weeks we are all in rehearsal working things out together, which is a luxuryKT I came here two years ago, a little bit before I had been to Glyndebourne for the first time, it was a day in March where people were busy in the workshops but there were no artists around , no rehearsals – it was just to see the place. A few months later I came to see a performance, and what it was like when the people make their picnics and so on, to get a feeling for this, and in between I had a feeling of what I would like to do.

Kate, this is your first time here.

KATE LINDSEY: Mm-mm. It’s not my UK debut: I sang at the Royal Opera House last year, I was singing Zerlina in Don Giovanni.

So to come here and have this luxury of working so intensely over such a long period of time – it’s presumably like nowhere else.

KL For me also this is a role debut so to have this amount of time, six weeks of rehearsals, is it?

KT Actually it’s seven.

KL - seven weeks of rehearsals, to become really intimate with the piece, and to have Vladimir [Jurowski, the conductor] here practically the entire time as well…so every day we are all in rehearsal working things out together, which is a luxury, because a lot of the questions and inquiries which happen between the music and the staging we can work out in that moment, find that in the moment of rehearsal, which then leads us on a much more calm, smooth, clear path as we move forward [laughs].

Did you start at the beginning or have you been doing rehearsals of sections out of sequence?

KT No, we were able to do it chronologically, which is always good.

It’s a funny situation in a way, isn’t it, because the Prologue is almost like a – terrible word – prequel, in that it was composed a couple of years after the original opera…

KT That’s true.

And it gives you introductions to themes that sometimes people who haven’t seen the opera will be introduced to… I love that point where the Dancing Master says that the opera’s terribly long and boring, and you actually have a quotation of Ariadne’s most beautiful melody. So it’s very rich in that respect. For me it’s one of Strauss’s few absolutely perfect acts, there’s not a false note.

KL I was just thinking about having this opportunity – I feel that when I’m approaching a role, a debut, and then you come back to it several years later, your understanding of the role has changed, and I was imagining Strauss, four years later to come back to composing the Prologue already knowing what the opera was. Having seen with the Bourgeois Gentilhomme [Hofmannsthal had originally adapted Molière's play in 1912, with incidental music by Strauss, inserting the opera in place of Molière's original ballet and prefacing it with a spoken backstage scene] how certain things worked and didn’t work, I think that probably created the opportunity. [Clicking fingers rapidly] it's just seamless, there’s never a moment when you’re asking why or what? It just moves, Vladimir says relentlessly, but in the most dramatic way, and I think maybe that's because they'd witnessed how the first version was received - not so well, it had some holes in it.

KL I was just thinking about having this opportunity – I feel that when I’m approaching a role, a debut, and then you come back to it several years later, your understanding of the role has changed, and I was imagining Strauss, four years later to come back to composing the Prologue already knowing what the opera was. Having seen with the Bourgeois Gentilhomme [Hofmannsthal had originally adapted Molière's play in 1912, with incidental music by Strauss, inserting the opera in place of Molière's original ballet and prefacing it with a spoken backstage scene] how certain things worked and didn’t work, I think that probably created the opportunity. [Clicking fingers rapidly] it's just seamless, there’s never a moment when you’re asking why or what? It just moves, Vladimir says relentlessly, but in the most dramatic way, and I think maybe that's because they'd witnessed how the first version was received - not so well, it had some holes in it.

They say partly because the theatergoers didn’t like the opera and the operagoers didn’t like the play aspect..

KL But then as a result it seems he almost inserted the theatre into the Prologue, he inserted what was lost, because it’s dialogue, sung dialogue.

And having Jurowski here presumably helps, even if you haven’t got the orchestra yet…

KT Yes, we have now [a week before opening night]. We had two stage and orchestra rehearsals on Wednesday and Friday, and the Sitzprobe happens on Tuesday, so they’re with us already.

And again I suppose it’s the joy of the small theatre and the small [37 piece] orchestra that you can absolutely dialogue with each other.

KL It’s incredibly intimate here. I think that’s why Ariadne in particular is really great for this theatre, because I sense that audiences respond to that sense of intimacy with the people on stage, with the orchestra, and to be able to create that ambience…in other houses you don’t have this particular sort of opportunity. For better or for worse [laughs] – here they can see it all!

One of the amusing things is that so many aspects of the opera are adumbrated in the prologue: the nature of the sets, the idea that people will sleep through the boring bits – and I imagine from experience that a lot of the less sensitive operagoers who come here because it’s Glyndebourne will have their picnic, drink lots of champagne and fall asleep during Ariadne’s arias.

KT That was why I was first concerned to make the opera interesting, to get that and keep that right up to the last chord.

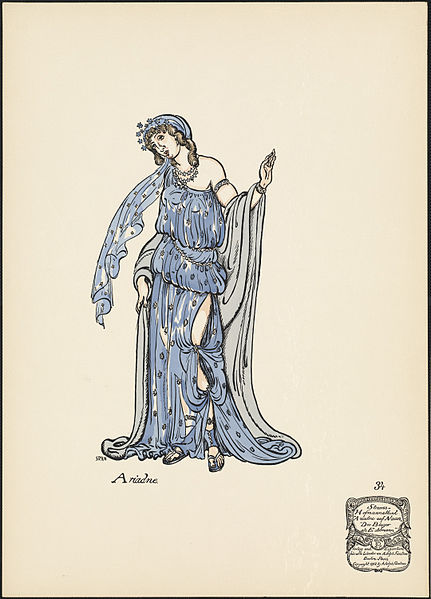

By making Ariadne [pictured below in Ernst Stern's design for the original 1912 version] a real human being.

KT That’s the word.

Because I’d heard from Cori [Ellison, Glyndebourne’s new dramaturg, in whose Study Morning the following day I was due to speak] a little bit about all this, that the opera is the same setting, a country house in the Second World War.

KT Yes, but it has changed its function.

So it’s later on in the war.

KT Maybe only a few months later, it fits very well into the united body, with the Battle of Britain, the time in the autumn when finally there was some hope, that the worst was over, and that a brighter future was maybe coming.

So is the Ariadne the same person as the Prima Donna preparing for the role in the Prologue?

So is the Ariadne the same person as the Prima Donna preparing for the role in the Prologue?

KT No, she’s not. There are other people we’ve seen before, like the Composer, who is very important…

[to KL] so you’re in the opera as well, watching?

KL I’m a silent participant.

KT But really important for everybody else around, and also for the very last moment, I think that’s just fantastic, to have the Composer there and to create this arch.

And is it the composer’s opera that’s being performed?

KT It’s not the composer’s opera but lots of the words mentioned in the opera, spoken by a very unhappy depressed woman who is a patient in this makeshift hospital, are very close to the words that the Composer has written, and so sometimes he is thrown back to what he has created without actually knowing what it meant at the time, without having gone through this experience – and now he sees somebody who is in that position, and he can think about what he’s written and take in what’s going on in front of him. I think that’s very helpful to make Ariadne a believable person, because here’s someone who feels compassion towards her, who understands quite a lot about what’s going on in her emotional inner life.

Usually the Composer is played as an adolescent, so do you mean him to grow up in the course of the opera?

KL Well, he's a very young man, that’s for sure, he sees also in this hospital other young men who have been seriously injured, one’s suffering from shell shock, for example, and he has actually been composing his music, he’s never been confronted with this, but now he sees other people who are much worse off.

And Zerbinetta’s commedia dell’arte troupe is a group of actor-performers who visit…

KT Exactly, sent by ENSA.

Well, that’s makes sense

KL Mm-mm. coming to cheer up the wounded.

KT Actually they manage to cheer everybody up except Ariadne..

KL She’s a hopeless case at that point, and my character understands, she and I have the same aesthetic there, we're quite annoyed with the troupe.

Christof Loy at Covent Garden also had the idea that it wasn’t the opera you saw everyone preparing for in the Prologue, Ariadne was a woman in a black dress – the famous black dress that Deborah Voigt had the issue with…[Both woman exclaim in recognition] She’s a woman who’s been deserted by her lover and in evening dress, so she also was a real person.

KT So he denied the play within the play. I think it’s wise. That was my first step towards this interpretation. Because if it’s a play within a play you have a singer – Soile Isokoski [pictured left] – singing the Prima Donna and in the second part Ariadne, and it’s so far away, whereas if it’s just somebody going through a very difficult period of her life and you’re just witnessing what’s going on without thinking is it a performance, is it real, on which level are we right now, it makes it more lifelike.

KT So he denied the play within the play. I think it’s wise. That was my first step towards this interpretation. Because if it’s a play within a play you have a singer – Soile Isokoski [pictured left] – singing the Prima Donna and in the second part Ariadne, and it’s so far away, whereas if it’s just somebody going through a very difficult period of her life and you’re just witnessing what’s going on without thinking is it a performance, is it real, on which level are we right now, it makes it more lifelike.

But also Zerbinetta, her coloratura aria…actually the text is very interesting, she’s not just a soubrette, is she – I mean when you get to the Pagliazzo, Mezzetin stuff It’s pure entertainment, but she is also a real person. You make Ariadne real too, so do they come closer in any way?

In the war, people had a few hours together, they went for it because next day they might be killedKT They do not understand each other, but in my opinion they are both broken hearted, and they both have damaged souls, with Ariadne it’s obvious, with Zerbinetta maybe not, but the way this aria is written, in this crazy style, so obsessive, somehow, and then there is one important line just after that bit which you just quoted, which shows she is pushed into something that she cannot control. I think she is as – insane is not the right word, as ill as Ariadne, and maybe from having had a similar experience. She has had so many lovers and everyone went away, and there was never an opportunity to make closer contact or to trust someone, which might also be fate in the war, because people had a few hours together, they went for it because next day they might be killed, so it is something very disturbing for a woman’s soul, and therefore I think the poor lady is really not that well.

[to KL] And your relationship with Zerbinetta in the Prologue, I mean, again it could be so ambiguous – in the text it says that she seems to be sincere but she sings with extreme coquetry, so is it taken seriously as a possible option?

KL The Composer takes her words seriously, but I think the way Katharina has worked with us is that she’s really saying these things in order to elicit this response from him, she is a woman who has had and continues to have many men, and she is very well versed in what is needed to be said in order to pull a man towards her, and in this particular instance she’s competing for attention. What bothers her is that the Composer sees her on some level but he’s still really in his own head, and that drives her crazy, she wants to maintain the control of the intention in the scene and the sexual intent, that she hasn’t achieved that, that’s what drives her.

So it’s a clash between sex and the more romantic ideal

KT Very idealized.

KL Oh yes, the Composer has a very idealized sense of romance, his ideal woman is Ariadne, who is true and loyal unto death, that’s what he’s searching for, and I think Zerbinetta does realize this, because she says, I think I could be true to the right person, and it’s, oh really, maybe she’s not what I thought she was, maybe it’s possible, but that’s human nature, how many times have we lived that as well, that’s not so far from reality, but that’s the ultimate dynamic between the two.

And does that develop in the opera?

KT I think he discovers a different side of her.

KL There's a particular interaction between Zerbinetta and the Composer in the opera, in which Zerbinetta can’t remember him at all – who are you? She’s had so many men – and in that moment that’s – breaking.

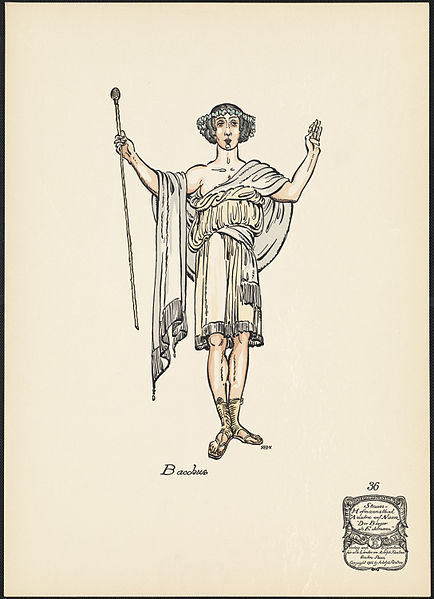

How do you make Bacchus [Stern's original design pictured right] work?

How do you make Bacchus [Stern's original design pictured right] work?

KT I tried to work out what a hero might have been in that time, and I heard quite a lot of stories about the Royal Air Force, and the people who fought for their country, the very few who saved so many other lives, so it was quite clear for me that he’s coming down from up there.

So he’s an RAF man.

KT Yes, he’s a pilot, and he happens to arrive in this hospital just by chance, he’s very confused because – we wanted to make him a parachutist, we had to make some adjustments in order to make it believable, so I hope people will still get the idea that he has come from something that was very dangerous, he saved his own life but maybe some of his comrades didn’t survive.

So that’s the way of looking at Bacchus’s experience with Circe, escaping from her enchantment.

KT Exactly, Circe for me wasn’t actually a very sexy woman or a witch, but I saw the experience as a symbol for death, all his friends were transformed into something – he wasn’t – but it might be animals, pigs, but it might be some other state of being, which means other life, and I think for him it’s very difficult to accept that he’s the only one who came through, and everybody else is dead. And then also when he describes his own situation, his mother’s death, because she died in the flames, and there’s a mythological connection to everything [Semele in the myth, who was burnt up on glimpsing Jupiter/Zeus’s true nature], but if you think – the poor man, his mother died in the flames, it’s not only about, I’m a god, I’m a hero, but he has feelings, it must be terrible to be left alone while everyone around him has died, like a bad conscience, something very disturbing.

As you speak, the whole thing suddenly makes sense, the whole issue of death becomes quite real.

KT And I think the first step that you have to take to make a person believable is like, OK, he’s a god, I have no idea what kind of feelings a god has, so let him stand there and speak and don’t bother about anything. If I try to understand what happens to someone who has lost many people around him, then he turns into something different, more human.

So two suffering people come together and you understand it better.

Tannoy: "ladies and gentlemen, we are moving on to Ford’s interior…"

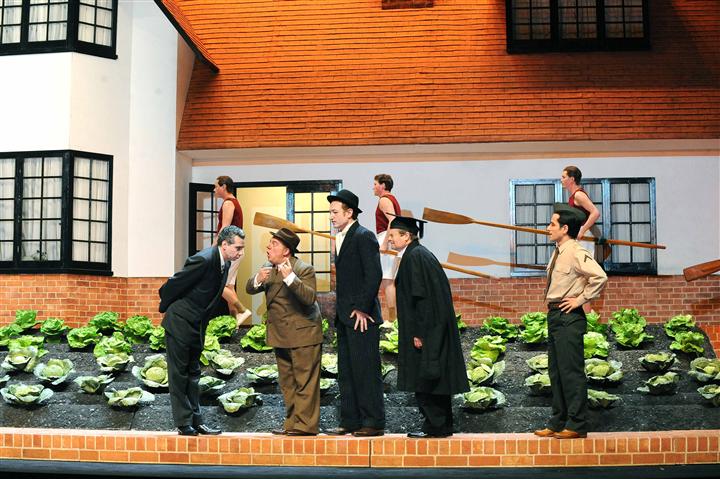

They're working on Falstaff. That’s a great production by the great Richard Jones [Act 1 Scene 2 pictured below by Mike Hoban], he’s got such imagination, don't you think?

KT He was my most important teacher. I worked with him only once, but it was the most important experience I had.

What was the work?

It was Billy Budd, in Frankfurt…

Which we’ve not had here.

KT Yes, the Michael Grandage production is the one here

...which is quite traditional, very straightforward. But how was Jones influential?

I understood that, I agree that every chord, every phrase in the orchestra has to have a relation to what’s going on on stage. So this Billy Budd, it was very clear, it was extremely strong, it was really thought through and it was always onward-moving so there was not one blank moment. And I think that’s really important if you want to get people’s attention and keep it through the whole piece, to really draw them into the piece you must keep hold of them all the time, and that’s what he did, by staging the whole music, every bar, everything. And that showed me how it should be.

I understood that, I agree that every chord, every phrase in the orchestra has to have a relation to what’s going on on stage. So this Billy Budd, it was very clear, it was extremely strong, it was really thought through and it was always onward-moving so there was not one blank moment. And I think that’s really important if you want to get people’s attention and keep it through the whole piece, to really draw them into the piece you must keep hold of them all the time, and that’s what he did, by staging the whole music, every bar, everything. And that showed me how it should be.

[to KL] Have you worked in a Jones production?

I did a Hansel and Gretel at the Met a couple of years ago, but I haven’t worked directly with him, because it was a revival.

But that was a brilliant concept. Which part did you play? Hansel or Gretel?

KL Hansel.

Because you’ve done soprano parts as well - you mentioned Zerlina...

KL Zerlina is zwischen [between]. These days there's a fashion for hearing an earthy mezzo in the role.

Because Mozart wouldn’t have made the distinction between soprano and mezzo.

KL There are phases. Sometimes you hear a soprano singing it very light, but it goes down into the lower areas of the voice. Sometimes it’s nice to play a girl, so I say yes.

As for the Composer, Lotte Lehmann created the part in 1916 and she was a soprano – it goes up to, what is it, a B flat, so you need a really full top..

KL One hopes…[big laughs]. That was the part that launched her career in Vienna, she stepped in for someone else, I think.

She presumably hadn’t sung Octavian [in Der Rosenkavalier]at that point, but still the Composer’s music, particularly the opening idea, is like an extended version of Octavian’s theme, Strauss makes that connection already. What a fantastic part, though, with that big ode to music in the Prologue, "Musik ist eine heilige Kunst", it’s just so marvellous.

KL It really comes down to the words, which are fantastic. Which is ironic because the words were written by Hofmannsthal, a poet, so for him to say "words are important but it’s the music", for him to say that as a passionate poet and writer, I find that very generous.

KT I think it may be also a bit of self-irony, there’s quite a lot.

What is especially is ironic is that the point at which you’re singing that, the orchestra is actually playing Zerbinetta’s aria in the pit…so when you’re singing those words you’ve actually got the Zerbinetta theme underneath. It struck me that Nietzsche phrase about sexuality reaching from the depths to the highest reaches. You think you’re singing about holy art, but you’re actually being influenced by what you’ve just experienced.

KL That’s true.

It’s terribly intense. When Maria Ewing [who sang the Composer the last time Glyndebourne staged the opera in the 1980s] came to the Proms for the semi-staged performance, I was standing near to some music students who said, she’s going to burn out, she can’t last…it’s a question of knowing how to give and balance.

KL Yes. It’s intense, but you just give your heart to it. There’s no way to do half way, its not fair, so you go into it knowing – it’s funny, it’s 40 minutes, but it’s probably the most tiring 40 minutes intensity wise, afterwards I’m, phew, please don’t, I can’t really have a coherent conversation, but it’s worth it, I’ve been looking forward to it. It’s funny, I can sing Nicklausse [in The Tales of Hoffmann] and be on stage for three hours, and that’s fine, I love the endurance of that, but this is a different animal.

Have you sung Octavian?

KL No, I haven’t. When I was starting out, I was thinking, what do you start with? Do you start with the Composer or do you start with Octavian? Octavian’s much longer, but vocally the range is slightly more condensed, it’s a little bit more mezzo in terms of range, but the decision was made for me, you can’t analyze it, the decision comes in and you think how old am I, you’ve just been singing this and that, OK, let’s do it, let’s see what happens here. It’s a process, this is the first time, and every performance will be different. That's the beauty of live theatre which you can’t get on TV or film, we will all evolve together and it will continue to evolve through a lifetime, hopefully.

Watch Kate Lindsey as Annio to Elina Garanca's Sesto in Mozart's La Clemenza di Tito

It’s a funny thing here because the final rehearsal can be more intense than the opening night – the audience is so full of conductors and singers…

KL It IS opening night. In some ways it’s good to get all of that out then, because in some ways in these last rehearsals we push to extremes in order to bring it all back to what’s real. You sort of have to go over that line in order to know where that balance is again.

[to KT] Do you feel the same?

KT Yes, I do. It’s also interesting to see what’s going on now since we have three orchestral rehearsals now, there’s something going on every day and developing, in this direction and that direction, and I try to respond to it, and it’s really something very passionate.

Jurowski works so hard on detail.

KL Very detailed

KT Absolutely.

And does that change things?

KT Definitely. Because he’s really taking part and asking questions, and there were some times when I had an idea about how to get into the next situation, how to bring in the next people, what to do in the background while other things are going on, and sometimes he helped me by moving the impulse half a bar in this or that direction, to move the impulse to some specific point I hadn’t thought of. I was nearly there but not quite. So that was fantastic. Because he really supported me in my ideas, but he showed me, OK, you just have to move it to the end of the bar instead of having it at the beginning of the bar, and that’s what happened when the composer asks for a sheet of music paper, which we have changed later on, but in the first moment he just showed me, do it there and it will work, and it was perfectly right, so that was great.

The theatrical pace – do you do straight theatre as well?

KT No, not yet – maybe one day.

Because there YOU dictate the pace.

KT Exactly.

Whereas here the music and the conductor dictate…

KL And the rhythm.

It’s conversational, parlando, until the Composer-Zerbinetta scene.

KL Yes, it’s a conversation not just between you and the other characters, it’s a conversation between you and the orchestra. And the ideas that pop in – boom – that’s the idea, you know? I think of it as a dance, you’re dancing between all these ideas that come together.

Did you look into the first version and has that formed anything that you’ve done?

KT No, not really. I saw part of it last year in Salzburg, they did the first version, and it convinced me that it was for good reasons that both Strauss and Hofmannsthal [pictured left in a silhouette by Bithorn], who were extremely theatrical and clever and wise persons, decided to go for something else. So it’s very interesting to see how that’s put together, and what’s in there, and so on and so on, but I think it’s just better to stick to what we have here.

KT No, not really. I saw part of it last year in Salzburg, they did the first version, and it convinced me that it was for good reasons that both Strauss and Hofmannsthal [pictured left in a silhouette by Bithorn], who were extremely theatrical and clever and wise persons, decided to go for something else. So it’s very interesting to see how that’s put together, and what’s in there, and so on and so on, but I think it’s just better to stick to what we have here.

I suppose the one thing which I used to question in the opera as you’re doing it is that Zerbinetta and her troupe don’t interact quite enough with Bacchus and Ariadne. Whereas in the original they do more, Zerbinetta comes back for another lengthy monologue towards the end. Isn't it fascinating, the opera as you do it ends with believing in the transcendentalism,but the original ends with irony, with Monsieur Jourdain [the Bourgeois Gentilhomme] alone on stage. The first and second times I saw the opera maybe the Ariadne wasn’t so great, so I didn’t quite believe in the ending. Sometimes you can end up loving the Zerbinetta and the high jinks more. The Composer you always love, I think. It’s part of the irony that in the Ariadne-Zerbinetta contest if Zerbinetta is Gruberova and steals the show, the Ariadne can be overshadowed. I don’t know your Zerbinetta…

KT It’s Laura Clayclomb, I think we were very lucky to find her. She can bring these qualitites that I see underneath the surface of this character, she can play it. She can sing it of course but she can express this very broken, interesting, diverse character.

Do you have the Harlequinade dancing?

KT The first quintet, yes, just imagine, it’s a performance organized by ENSA, so these people are sent to the hospital, they do their Lindyhop, they do their Charleston thing, it’s really lovely – we have a very good choreographer for that, someone who’s done a lot of work with Richard Jones as well, that’s why I know her, Lucy Burge, so I asked her if she would join me at Glyndebourne and I was very happy that this was possible - and the second quintet is more a hide and seek game.

The four men aren't very often differentiated.

All four of our boys are quite some characters, and because of who they are, the way they go for it, it’s quite gorgeous.

So in short, you’re happy with the way it’s going.

KL We’re ready. We’re ready to have an audience, to share it.

KT That’s a very strange feeling I had, was it already two weeks ago? It was the first day on stage, a Saturday, and I was sitting in this empty auditorium and I was looking at these people and I thought, we should have an audience. Because we ran the Prologue and I thought, my God, it’s really there, they’re pretty fine, and it’s strange I am here on my own, because it should be full.

The laughter should change things, though again because it’s an opera and not a play the laughter can’t change the pace, you notice even with consummate comic actors that the more the audience laughs, the more they mug, they slow it down, and sometimes in a good way, as with Mark Rylance at the Globe, he’s fantastic with an audience, but it can add 20 minutes on to a show.

KL One of the things of having the orchestra there is that we can’t always hear the laughter, unless it’s really raucous, because of the orchestra and being in the moment. Vladimir would NOT allow us to play up [laughter from both].

Supertitles can sometimes induce the laughter before the lines have been sung.

KT You have to time it. That’s one of the things that are really important, that’s something I learnt with Christof Loy, because he always corrects supertitles, and also tries to have an equivalent for something that people found funny 200 years ago, so if there was a joke for them in that time there needs to be a joke for our time also. You have to adapt the translation and you have to check when you bring the lines up. It’s part of the game.

KT You have to time it. That’s one of the things that are really important, that’s something I learnt with Christof Loy, because he always corrects supertitles, and also tries to have an equivalent for something that people found funny 200 years ago, so if there was a joke for them in that time there needs to be a joke for our time also. You have to adapt the translation and you have to check when you bring the lines up. It’s part of the game.

This is such an exquisite text, isn't it. Until you get to Rosenkavalier you wouldn’t have believed Hofmannsthal could write such comedy, and it always seems rather odd to me that he should dwell so much on the heavy stuff – that wonderful correspondence where Strauss says, that’s all very good but your ideas might not be embodied in the action. In a sense you [to KL] set it up because you sing about the themes that Hofmannsthal wants, and it seems to me that Strauss and Hofmannsthal have corrected that misunderstanding in allowing the Composer to lay out the ideas with all the wonderful themes of the opera going on underneath as well. You're the interpreter.

KL And my understanding is that Strauss was very nervous about the Composer, he said very clearly, I do not want this character based on me, so they sort of agreed it was more of a Mozartian character, and then that allowed him the freedom to create something that was much more…I can only physicalise that Mozart sense of liveliness, of energy, to infuse that into the music.

A bit like Cherubino via Octavian

KL Exactly.

But Hofmannsthal didn’t like the idea of a woman singing the Composer.

KL There was certainly some discussion. The funny thing about the two of them is that they rarely saw each other face to face, they would just correspond, and ironically Strauss as the composer was very low key and laid back about it. I think the Composer is much more Hofmannsthal than Strauss, he would push and push and write these very emotional letters.

KT I think he contributes about two thirds of the correspondence, or maybe even 75 per cent, and sometimes he’s pushing Strauss, why didn’t you write back, I need this, he gets very upset.

One of the reasons about casting the Composer as a woman was that the mezzos in the companies were better actors than tenors.

KL Well that too, I think for them after the huge success of Rosenkavalier being that it wasn’t so far fetched to put a female into that role…I’m sure they thought it over.

Again, isn't it wonderful that in the revised version all the ruckus in the correspondence is resolved – the Prologue answers all the questions.

I find it more exciting that changes to the production are happening all the timeKL A story like this is reassuring for me, because it reminds us that even the very greatest have had their moments where the first version didn’t work out so well, and there’s that reminder that you can always come back to something and always rethink it, always revise, it gives you that sense of hope that that’s how inspiration and success are achieved – potentially you fail many times before you find the greatest success, and it’s only through that you discover the core truth of what this opera is, finding the connection between the opera and the Prologue that brings it out in its best light.

Katharina, do you constantly change things if they're not working?

KT Yes, only yesterday I did something. If I have a feeling that something’s too dangerous, that it’s going in the wrong direction, I have to change it…we havd rehearsed that particular aspect for two weeks or longer and then I decided it was too much of a risk, that it didn’t work. And if people don’t follow me in this, then it’s so dangerous to lose quite a lot of their belief and conviction.

It’s like Kupfer directing the Ring, getting characters to come charging on, and them saying, well I don’t know, and he said, well, try it, and if you’re happy with it, fine, if not, we’ll change it. You can’t be inflexible with singers, can you?

KL In some ways I find it more exciting that changes are happening all the time, it keeps us on our toes to have to change and adjust. I know some people don’t like it, but I enjoy it because it makes it feel as if you’re in a process of continunal evolution, which I find very comforting.

KT Isn’t that written into the Composer’s part?

KL There’s always, at the eleventh hour, the feeling, oh, I wish I’d done this. But like I said, we're ready now.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Add comment