Relatively Speaking, Wyndham's Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Relatively Speaking, Wyndham's Theatre

Relatively Speaking, Wyndham's Theatre

Early Ayckbourn play fizzes anew 46 years on

The pronouns have it in Alan Ayckbourn's career-defining comedy of spiralling misunderstandings, which has arrived on the West End 46 years after first hinting at the formidable talent of a dramatist who could make of many an "it" and "she" a robustly funny study in two couples in varying degrees of crisis.

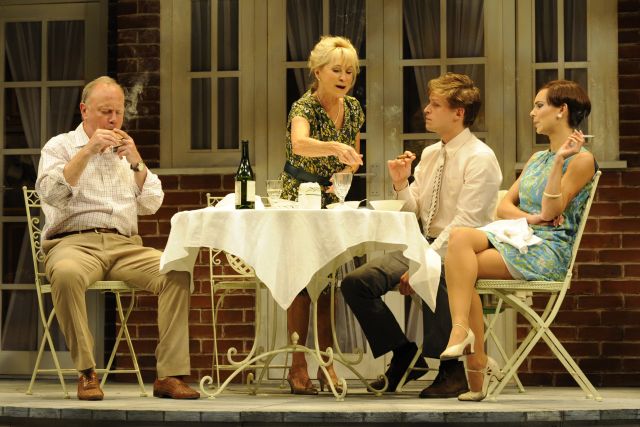

A portrait of two partnerships - one but a month old though already on the road to marriage, the other well-established and near the point of ruin - Relatively Speaking takes an apparently simple conceit and pushes it to a perilously funny extreme. The loved-up Greg (a sweetly oblivious Max Bennett) decides to pay a surprise visit on the parents of the bewilderingly evasive girlfriend, Ginny (Kara Tointon, pictured above, her look to the Mary Quant manner born), whom he hopes to marry. Instead, a well-intentioned train journey to deepest Buckinghamshire lands Greg in the garden of a long-married couple who haven't the faintest idea who he is and won't until many a slow burn and double take have come to pass. And some while after "daddy" has acquired various meanings well beyond the merely paternal.

A portrait of two partnerships - one but a month old though already on the road to marriage, the other well-established and near the point of ruin - Relatively Speaking takes an apparently simple conceit and pushes it to a perilously funny extreme. The loved-up Greg (a sweetly oblivious Max Bennett) decides to pay a surprise visit on the parents of the bewilderingly evasive girlfriend, Ginny (Kara Tointon, pictured above, her look to the Mary Quant manner born), whom he hopes to marry. Instead, a well-intentioned train journey to deepest Buckinghamshire lands Greg in the garden of a long-married couple who haven't the faintest idea who he is and won't until many a slow burn and double take have come to pass. And some while after "daddy" has acquired various meanings well beyond the merely paternal.

Husband Philip (Jonathan Coy, splendidly splenetic) knows Ginny all right, not as a daughter but as his ongoing mistress in an affair that the young newlywed-in-waiting wants to bring to an end. Ginny's plans, in turn, fail to account for Philip's beamingly ditzy wife, Sheila (Kendal), who is erroneously taken to be the randy Greg's intended, thereby fulfilling Philip's deepest suspicions about his chipper if possibly none-too-faithful spouse. "I've mislaid the hoe," snarls Philip in a cascading fury at events that find errant garden implements to be the least of his worries. Ginny arrives in time for Tointon to further furrow her brow, the actress as voluble here as she was (deliberately) sullen and indrawn a season or two ago in the same dramatist's Absent Friends.

A short play (less than two hours, interval included) is a marvel of construction that effortlessly folds the pressure of symmetrical train journeys into a city-vs-country gavotte that nods glancingly to Wilde while anticipating the far darker forays into the partnered psyche that would go on to be Ayckbourn's proven terrain. What enchants as well on this occasion is the period modishness of Peter McKintosh's poster-perfect design - Breakfast at Tiffany's on the lovers' London wall, the lunch from comic hell on the suburban menu - set against our burgeoning sense of Sheila as possibly the most astute figure on a greenery-bedecked stage on which Kendal is forever bustling about, proffering refreshment as the realisations come home to roost (the four actors are pictured above.)

A short play (less than two hours, interval included) is a marvel of construction that effortlessly folds the pressure of symmetrical train journeys into a city-vs-country gavotte that nods glancingly to Wilde while anticipating the far darker forays into the partnered psyche that would go on to be Ayckbourn's proven terrain. What enchants as well on this occasion is the period modishness of Peter McKintosh's poster-perfect design - Breakfast at Tiffany's on the lovers' London wall, the lunch from comic hell on the suburban menu - set against our burgeoning sense of Sheila as possibly the most astute figure on a greenery-bedecked stage on which Kendal is forever bustling about, proffering refreshment as the realisations come home to roost (the four actors are pictured above.)

Looking over her shoulder as if expecting some better, more truthful existence to make itself known, Kendal hasn't been this well cast in ages, her signature winsomeness replaced by a deliciously dim aspect that is itself shown to be far from the whole truth. And what will happen in the sequel to events that Ayckbourn didn't write? For all the chatter about the summer sun, one senses storm clouds brewing. This is Ayckbourn territory, after all, which means that happiness is only relative. Give these people and their playwright time, and make way in due course for madness.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Interview, Riverside Studios review - old media vs new in sparky scrap between generations

Robert Sean Leonard and Paten Hughes make worthy sparring partners

Interview, Riverside Studios review - old media vs new in sparky scrap between generations

Robert Sean Leonard and Paten Hughes make worthy sparring partners

Fat Ham, RSC, Stratford review - it's Hamlet Jim, but not as we know it

An entertaining, positive and contemporary blast!

Fat Ham, RSC, Stratford review - it's Hamlet Jim, but not as we know it

An entertaining, positive and contemporary blast!

Juniper Blood, Donmar Warehouse review - where ideas and ideals rule the roost

Mike Bartlett’s new state-of-the-agricultural-nation play is beautifully performed

Juniper Blood, Donmar Warehouse review - where ideas and ideals rule the roost

Mike Bartlett’s new state-of-the-agricultural-nation play is beautifully performed

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - breathtakingly audacious, deeply shocking

A cunning ruse leaves audiences facing their own privilege and complicity in Cliff Cardinal's bold theatrical creation

As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - breathtakingly audacious, deeply shocking

A cunning ruse leaves audiences facing their own privilege and complicity in Cliff Cardinal's bold theatrical creation

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Refuse / Terry's / Sugar

A Ukrainian bin man, an unseen used car dealer and every daddy's dream twink in three contrasting Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Refuse / Terry's / Sugar

A Ukrainian bin man, an unseen used car dealer and every daddy's dream twink in three contrasting Fringe shows

Faustus in Africa!, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - deeply flawed

Bringing the Faust legend to comment on colonialism produces bewildering results

Faustus in Africa!, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - deeply flawed

Bringing the Faust legend to comment on colonialism produces bewildering results

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Imprints / Courier

A slippery show about memory and a rug-pulling Deliveroo comedy in the latest from the Edinburgh Fringe

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Imprints / Courier

A slippery show about memory and a rug-pulling Deliveroo comedy in the latest from the Edinburgh Fringe

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Ode Islands / Delusions and Grandeur / Shame Show

Experimental digital performance art, classical insights and gay shame in three strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Ode Islands / Delusions and Grandeur / Shame Show

Experimental digital performance art, classical insights and gay shame in three strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Ordinary Decent Criminal / Insiders

Two dramas on prison life offer contrasting perspectives but a similar sense of compassion

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Ordinary Decent Criminal / Insiders

Two dramas on prison life offer contrasting perspectives but a similar sense of compassion

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Kinder / Shunga Alert / Clean Your Plate!

From drag to Japanese erotica via a French cookery show, three of the Fringe's more unusual offerings

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Kinder / Shunga Alert / Clean Your Plate!

From drag to Japanese erotica via a French cookery show, three of the Fringe's more unusual offerings

The Two Gentlemen of Verona, RSC, Stratford review - not quite the intended gateway drug to Shakespeare

Shakespeare trying out lots of ideas that were to bear fruit in the future

The Two Gentlemen of Verona, RSC, Stratford review - not quite the intended gateway drug to Shakespeare

Shakespeare trying out lots of ideas that were to bear fruit in the future

Add comment