Heaven's Gate | reviews, news & interviews

Heaven's Gate

Heaven's Gate

Michael Cimino's calamitous Western about an 1890s range war grows in stature

Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate is the most Melvillean of modern Westerns. It is the American conquest tragedy allegorised in a sprawling semi-fictional account of the 1892 Johnson County range war, in which the big ranchers of the Wyoming Stock Growers’ Association, supported by President Benjamin Harrison, waged a vigilante campaign against the region’s small farmers, settlers, and rustlers.

Cimino included the conflict’s two most fabled incidents. One was the brave stand of a cowboy, Nate Champion (played by Christopher Walken as a Regulator losing favor with the command), who fought all day against Canton’s men until he was forced from his burning ranch house and cut down. The other was the surrounding of the Regulators by a 200-strong posse raised by the settlers (George Stevens’s 1953 masterpiece Shane had told the story in microcosm.)

The writer-director envisioned a mythic account of the war that pitched the xenophobic capitalist cattlemen against impoverished European immigrants (wagons roll west, pictured right). The maker of The Deer Hunter, Cimino may have had the Vietnamese peasants resisting of the America military-industrial complex in mind. Mythic, too, are the film’s protagonist and his woman. Jim Averill (Kris Kristofferson) is a Harvard graduate and frontier gentleman who has broken with the landowners to side with the immigrants, but wavers too long before rallying them to fight back after they have taken a mauling. His indecision is partly attributable to his involvement with the French prostitute and brothel-keeper Ella Watson (Isabelle Huppert), whom he loves but will not marry.

The writer-director envisioned a mythic account of the war that pitched the xenophobic capitalist cattlemen against impoverished European immigrants (wagons roll west, pictured right). The maker of The Deer Hunter, Cimino may have had the Vietnamese peasants resisting of the America military-industrial complex in mind. Mythic, too, are the film’s protagonist and his woman. Jim Averill (Kris Kristofferson) is a Harvard graduate and frontier gentleman who has broken with the landowners to side with the immigrants, but wavers too long before rallying them to fight back after they have taken a mauling. His indecision is partly attributable to his involvement with the French prostitute and brothel-keeper Ella Watson (Isabelle Huppert), whom he loves but will not marry.

One of Cimino’s mistakes was to depict Jim and Ella as ecstatically happy lovers before revealing that she also loves the less refined but smitten Nate, one of her paying clients and, despite his murderous work for the Regulators, a friend of Jim. In reality, Averill was a homesteader and Watson a rustler who had cohabited; they were lynched by WSGA vigilantes in 1889, and the seizing of their separately owned ranches by the cattle men contributed to the class animosity (Kristofferson in the saddle, pictured below).

The movie’s love triangle often seems tangential to the coming storm and supplants it for much of the second act. Gradually, it sucks the viewer in. Heaven’s Gate may not be Jules et Jim, but Cimino excelled in the crafting of Ella’s intimacies with each lover: her foreplay with Jim is an occasion for laughter; the tenderness she feels for Nate is sometimes mixed with amusement, as when she takes tea with him at his cabin and he proudly reveals that he has civilised it by decorating the walls with old newspapers.

The movie’s love triangle often seems tangential to the coming storm and supplants it for much of the second act. Gradually, it sucks the viewer in. Heaven’s Gate may not be Jules et Jim, but Cimino excelled in the crafting of Ella’s intimacies with each lover: her foreplay with Jim is an occasion for laughter; the tenderness she feels for Nate is sometimes mixed with amusement, as when she takes tea with him at his cabin and he proudly reveals that he has civilised it by decorating the walls with old newspapers.

These kinds of small details were also apparent in John Ford’s epic silent Westerns The Iron Horse (1924) and 3 Bad Men (1926), which, similarly engaged with pioneer imperialism, must have influenced Cimino. So, too, Samuel Peckinpah’s blend of observational realism and hyperbolic action in The Wild Bunch (1969) and the Kristofferson film Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973).

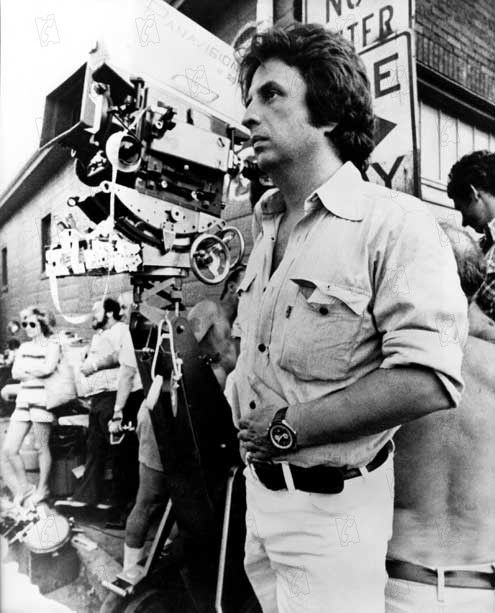

The carefully restored Heaven’s Gate that’s being released in the UK tomorrow is 216 minutes, Cimino (pictured right) having cut from it the original’s intermission and made a few trims. An intermission is necessary here, however, to mention the saga of hubristic creation and disastrous reception without which, sadly, no discussion of the film is complete.

The carefully restored Heaven’s Gate that’s being released in the UK tomorrow is 216 minutes, Cimino (pictured right) having cut from it the original’s intermission and made a few trims. An intermission is necessary here, however, to mention the saga of hubristic creation and disastrous reception without which, sadly, no discussion of the film is complete.

Working on a budget of $11.5 million on location in Montana in 1979, Cimino reportedly shot 220 hours of footage at a cost of $44 million. The cut of 325 minutes he showed to United Artists executives in June 1980 was reduced to 219 minutes for the November 1980 release. Following a reportedly funereal premiere and vicious reviews, the film was pulled from cinemas after a one-week run. Cimino recut it to 149 minutes for a run in Los Angeles in April 1981. It lasted two weeks. The total domestic gross was less than $3.5 million; the loss $40.5 million.

UA nearly went bankrupt. Cimino’s career was ruined. The man who had gone into Heaven’s Gate as the Oscar-winning director of 1978’s Best Picture-winner The Deer Hunter has made only four films since, all box office failures (not that making money is a guarantee of quality). Did Heaven’s Gate bring on the twilight of the mainstream auteurs? It was followed by Francis Coppola’s One From the Heart (1982) – most magical of failures – and the Warren Beatty-produced dud Ishtar (1987). But, no – Spielberg, Scorsese, Eastwood and others continued to thrive. And Silverado and Pale Rider were just five years off.

What a riven America 'Heaven's Gate' shows, and what an event it remains

Though Cimino’s visionary reach matched Coppola’s, he may have been closer in spirit to Erich von Stroheim, another perfectionist who at Universal and Goldwyn in the early 1920s never knew when to stop spending and shooting. I’d argue there is something exciting about an egomaniacal obsessive pursuing a folie de grandeur to the bitter end, and that cinema’s equivalent of 19th-century novelists’ baggy monsters can fire the imagination as much as movies made with tension, discipline, and editorial economy.

Heaven’s Gate has none of those qualities, but it does boast some of the most breathtaking sequences ever filmed. A master of set-pieces, as he had shown with the great wedding passage in The Deer Hunter, Cimino filled his Western with them. There is the nostalgic prologue which, celebrating the Class of 1870 during speech day at Harvard, embraces music and dance and establishes the moral frivolousness of Jim’s friend Billy Irvine (John Hurt, pictured below), who will fetch up in Wyoming as a Fordian drunk spouting literary quotes.

There is Jim’s shopping expedition to the giant outfitting store in Casper, Wyoming, which teems with landowners and their managers buying the tools to complete Manifest Destiny. The roller-blade dance, led by the graceful boy fiddler, at the rink built by Jim’s closest ally, the entrepreneur John L Bridges (Jeff Bridges), is Cimino at his most lyrical. The climactic battle, in which the grenade-lobbing immigrants advance like Roman legions on the encircled Regulators, is Cimino at his most martial. Cinematographer Vilmos Szigmond lit the film not unlike he did Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs Miller (1971). Though in color, the town scenes have a vintage glow that suggests the sepia of 19th-century daguerreotypes; Deadwood (2004-06) and The Assassination of Jesse James By the Coward Robert Ford (2007) were legatees.

All of these sequences and many of the others needed cuts. They also needed splicing together with more punctuation and with a greater sense of narrative urgency. The writing is often flimsy. Walkern’s angsty Nate and Huppert’s mercurial Ella are tinged with modernity, though Kristofferson’s Jim – “I’m gettin’ old” – strikes the right note of period gravitas. In places, the film’s beauty weighs so heavy on it that it becomes monotonous. But what a riven America Heaven’s Gate shows, what greed it exposes – and what an event it remains.

All of these sequences and many of the others needed cuts. They also needed splicing together with more punctuation and with a greater sense of narrative urgency. The writing is often flimsy. Walkern’s angsty Nate and Huppert’s mercurial Ella are tinged with modernity, though Kristofferson’s Jim – “I’m gettin’ old” – strikes the right note of period gravitas. In places, the film’s beauty weighs so heavy on it that it becomes monotonous. But what a riven America Heaven’s Gate shows, what greed it exposes – and what an event it remains.

- Heaven's Gate is showing at BFI Southbank and selected cinemas from Friday 2 August

- Visit the website for distributors Park Circus

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Add comment