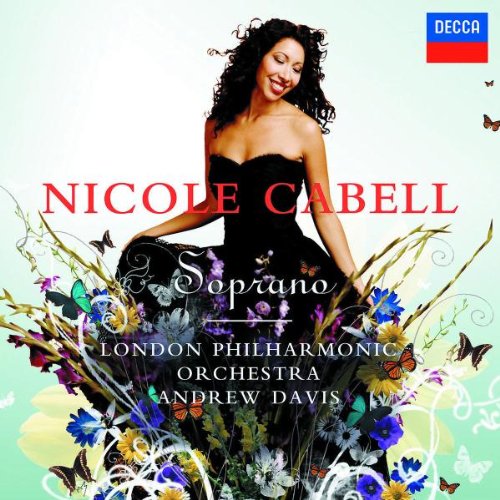

Last year a DVD appeared featuring the 15 winning performances from the start of the BBC Cardiff Singer of the World Competition up to 2011. I watched them all, skimming if any seemed a notch below par but staying with most. You could see the star quality and the promise in many who have since become great artists, including Karita Mattila, Anja Harteros and Ekaterina Shcherbachenko. But only two seemed like the fully finished article from the start: Siberian baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky in 1989 – the year Bryn Terfel won the Lieder prize – and American soprano Nicole Cabell in 2005, the equal of compatriot mezzo Jamie Barton who took the most recent prize.

I’ve only caught Cabell live in action twice since then: once as the stand-out in a Royal Opera concert performance of Bizet’s Les pêcheurs de perles conducted by Antonio Pappano, and two Mondays back in a deeply moving performance of Samuel Barber’s Knoxville: Summer of 1915. By opportune scheduling, she’s returning to London to sing the soprano solos in Elgar’s The Apostles with Sir Andrew Davis and the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the Barbican this coming Saturday. We met the day after the Barber performance, when she was obviously still suffering from the heavy cold which had postponed our interview and which I’d forgotten about when I watched the performance. Technique had carried her through, she said, and she hadn't wanted to make an announcement, but the words weren’t as clear as she would have liked as a result of the infection – my only criticism in a hymn of praise. The obvious starting point was what she thought about a difference between the 2005 turning-point (pictured below) and now.

DAVID NICE: I don’t know how you’ve felt about that Cardiff performance since, but it seemed close to perfect to me.

DAVID NICE: I don’t know how you’ve felt about that Cardiff performance since, but it seemed close to perfect to me.

NICOLE CABELL: I appreciate that – it’s an incredible compliment. It’s funny because we singers reckon hell will freeze over before we win something like that, and now I look at it and think, there’s a million things I did wrong and could do better now. Of course I guess if I got to the point where I didn’t see a flaw in my voice I should probably retire.

So how in your perception has the voice matured since then?

It has been a long time. There are certainly things in the Mozart performances which strike me when I see it, because I hadn’t sung a complete Mozart opera at all up to that point, I’d never even performed any of Ilia’s arias [from Idomeneo]. And 2006 was my first Pamina [in The Magic Flute] at Palm Beach, Florida: I learned through the course of that how to approach Mozart. Otherwise, stylistically things have changed a lot. In terms of the voice, my middle range is developing, and the sound is getting a little bit fuller, and this is the direction I wanted to go in then. But we’re almost 10 years on, and I’m singing some repertoire which is a little bit more reflective of that, so Mimì's coming up [in Puccini’s La Bohème].

So you’re heading towards lirico-spinto repertoire?

Heading in that direction, yes. But although my voice is getting richer and darker, I think the volume is always going to be the question mark, especially in the sort of houses we sing in throughout America – singers will tell you horror stories of singing in barns, because we don’t have a lot of houses there really adapted really to the human voice.

The Met is huge.

The Met is huge, and much as I enjoy singing there for the honour of it, I find it’s simply too big for my voice, whatever repertoire, and I find that when I’m on stage I’m always competing to be heard. My voice is a soft-grained voice, it’s warm and I do have a cut, but it’s not a steely voice. I find the Royal Opera House is a perfect acoustic, half the size of the Met. What I would really like to do is sing roles that are a little bit more mature in colour like Mimì, and continue to sing the richer Mozart roles like the Countess and Fiordiligi, and Verdi’s Violetta, possibly something like Gounod’s Marguerite - I don’t know about that yet - in houses that are the size of the Royal Opera or smaller, in Europe, because there aren’t a lot of houses like that in America. So far I’ve done a lot of concert work overseas and a lot of opera in America. Sometimes it just happens like that in the course of a career – one soprano, say, gets perceived as a Strauss specialist and once you get a reputation it’s a little bit more difficult to break through in the other genres.

Wouldn’t Strauss be a perfect next step? I thought so when I heard you in the Barber.

That’s something I’ve always wanted to do. I’m actually learning the Four Last Songs to try out; oddly it’s similar in some ways to the Knoxville, there are many of the same nostalgic sentiments. All I’ve sung before was Sophie 10 years ago in concert, but perhaps some of the Strauss heroines are roles I can do in smaller European houses.

Glyndebourne is somewhere I thought would be perfect for you – I imagine you’re a singer who loves to work in depth and detail, someone who likes long rehearsal periods.

I do…

And Glyndebourne’s the place where the former music director Vladimir Jurowski liked to be present from the first piano rehearsal, and now his successor Robin Ticciati is the same.

That is incredible, it’s something that a lot of people have told me about. The economy and business of opera have changed so much. We hear a lot about that sort of thing from the so-called golden age singers, from let’s say the 1930s to the 1960s, who had access to more time to develop as artists but also to have a specific vision realised with an amazingly talented conductor. I’ve experienced that a couple of times – especially with Andrew Davis. Andrew and I go back quite a way [he conducts her debut disc on Decca, Soprano] Then there were Roger Norrington in Cincinnati, Riccardo Frizza in San Francisco for I Capuleti e i Montecchi and Emmanuel Villaume in San Diego for Les pêcheurs de perles. But it’s not the norm.

That is incredible, it’s something that a lot of people have told me about. The economy and business of opera have changed so much. We hear a lot about that sort of thing from the so-called golden age singers, from let’s say the 1930s to the 1960s, who had access to more time to develop as artists but also to have a specific vision realised with an amazingly talented conductor. I’ve experienced that a couple of times – especially with Andrew Davis. Andrew and I go back quite a way [he conducts her debut disc on Decca, Soprano] Then there were Roger Norrington in Cincinnati, Riccardo Frizza in San Francisco for I Capuleti e i Montecchi and Emmanuel Villaume in San Diego for Les pêcheurs de perles. But it’s not the norm.

When you won Cardiff I believe you had just come to the end of an intensive three-year training programme at the Chicago Lyric Opera.

Yes, that had only finished a couple of months before.

So you hadn’t had that much stage experience.

I hadn’t. I learned my craft in front of everybody, which was good experience. I’m very grateful not to have had a huge limbo or purgatorial period when you’re out of training before you begin a career – I was able to start working right away. At the Lyric I did a couple of covers and small roles. It was such a great programme because we had what they called buddy coachings, certain artists would come and we would be able to request coaching with them, so I was able to work with Natalie Dessay, Elizabeth Futral, Isabel Bayrakdarian. One of the first things I was able to do was to sing a small role in Massenet’s Thaïs with Renée Fleming and Thomas Hampson, and I was this close to Renée, that was my first year… I was watching her mouth to see exactly what was going on with the mechanisms and the resonators and the tongue, I was in there like a scientist, she was amazing and that kind of set the scene for me to make sure that whatever I did I never lost sight of what it was to be around somebody that fantastic at a high artistic level. She and Thomas worked in a completely different way, but that was the first time we saw a level of professionalism that was mind-scrambling and seemed unachievable.

Working backwards, did you have a natural musical background?

Not an operatic one, no, my mother would play The Doors and Joni Mitchell…

Who is a great example for any singer.

She’s incredible. And I heard plenty of musicals at home, my mother was obsessed by Phantom of the Opera, and there was Rodgers and Hammerstein all the time. A lot of American singers performed in Rodgers and Hammerstein at high school, which is not a bad tradition. It gets you comfortable, it puts you in front of people in a conversational, easy, not so academic way at the beginning, and that’s good for younger people. In my youth I sang in only one musical, Once on This Island, by Lynn Arens and Stephen Flaherty, the people who did Ragtime, that was my first and later I was in Kismet, and that’s classical in a way – after all, the melodies are Borodin’s.

But quite a tricky piece to put on now, as we found out when it was staged here. And there are musicals like Flower Drum Song which they thought could only work on Broadway with a new book.

It’s a risk you take – when you put on The Magic Flute (Cabell as Pamina, right, with Stéphane Degout as Papageno) you have to figure out how to change the sexism and racism. Nobody does anything about the sexism.

It’s a risk you take – when you put on The Magic Flute (Cabell as Pamina, right, with Stéphane Degout as Papageno) you have to figure out how to change the sexism and racism. Nobody does anything about the sexism.

Oh, I don’t know, Barbara Hendricks told me how strong Pamina is – how she leads Tamino through the trials, it’s only Sarastro’s brotherhood that's sexist and needs changing.

If you’re smart enough to read the subtext… But that’s a good point and a couple of times I’ve done stagings where I do the leading, but half the time I sing "I will lead and guide you", but he still ends up leading me everywhere. Maybe I should make more of a stand with the director.

It’s usual to change the language and cut the dialogue. Monostatos is rarely black.

No, he’s green or blue or something freakish, but please God not black or Moorish…isn’t it terrible? But you do have to make concessions. I sang Kismet in 1996 and it’s hard for me to remember how unPC it was. But you just have to take it for what it is.

Your first singing training was in opera?

Kismet came around the time of my first studies – I took lessons at 15 in Ventura, California which is where I grew up, and within a couple of months I was singing classical music, because I tried singing Broadway and musical theatre, pop music, jazz, and it all just came out sounding operatic. It’s as simple as the fact that you’re born with a certain range. If I were to have you singing scales, we’d probably find you were a baritone.

Well, I did belong to an opera group 25 years ago, but I don’t think the voice was so developed – I could go up to tenor or down to bass. They say that the majority of British men are baritones that are pushed up or down.

Isn’t that funny? It’s like there’s something in the biology of the body, the height and the bone structure, that will determine what range, what Fach you’re destined for. Let’s face it, there’s a lot of Mexican and Italian tenors, for example. The ethnicity of someone will influence the colour of the voice.

Continued overleaf

[We change places on the sofa as the sun is in my eyes and Nicole needs her vitamin D. Which leads to a long digression on open spaces in London and praise of this city: "Can I say I’m jealous of you, I love London so much and it’s difficult to relocate, but I think anyone who lives here, if they appreciate it they’re blessed. But you have to be able to afford it and it’s becoming too expensive. As in New York, it can really be an uncomfortable life if you don’t have money." And so to English music].

It amazed me that you sang that aria from Tippett’s A Child of Our Time at the Cardiff final (left, Cabell in concert). And now you’re doing The Apostles. I’ve fallen in love with the piece. It has so much profound sadness about it..

It amazed me that you sang that aria from Tippett’s A Child of Our Time at the Cardiff final (left, Cabell in concert). And now you’re doing The Apostles. I’ve fallen in love with the piece. It has so much profound sadness about it..

It has, and it’s very Wagnerian, right, you think it’s going somewhere and it changes and changes so you just go with it, it’s like riding a wave. Especially the second half, it’s hypnotic. The first part is storytelling, quicker moving, you’re not quite aware of that emotion. I was listening to it the other day and by the end I was… not in a low place, but heavy-hearted.

There was that sadness in Elgar himself - I think he identified with Judas the disappointed man.

This is my introduction to Elgar, it’s fascinating, and when I listened to it at first for what I had to sing, I discovered my roles are participatory and they comment on the action but I don’t advance anything plot-wise. But then I listened to the rest of it, and the scenes for Mary Magdalene are so operatic in scale, very intense. It’s an honour just to be doing this with these incredible singers.

And now Andrew Davis is the Elgar conductor par excellence.

He’s extraordinary, he’s a genius, we’ve worked together for a long time, I’ve been able to get inside his brain, it’s just incredible – the things you can learn from him – well, we talked before about gleaning insight from a great maestro. And time is a privilege, we have three whole days of rehearsals which for a concert is good. But going back to what you were saying, the English repertoire link is just coincidental.

Had you sung the Tippett before you performed it in the Cardiff final?

Yes, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Andrew conducting. The most difficult part of Cardiff was coming up with something that fit their requirements. Each slot was 15 minutes with different styles, different languages, and at first I thought, is this appropriate or not? But the repertoire choices worked out well from the earlier rounds - I thought people would know Menotti, would be bored wih Capuleti, and the Tippett – you don’t know, it turned out they responded well, I was happy about that but I just love the piece and it suited me very well. It was a no-brainer for me.

So it’s coincidence that you’re doing the Elgar – but I sense you’re open to adventure.

I wanted my trademark at a point in time to be slightly unusual repertoire. That’s why when I was on the Chicago programme I looked for the most obscure rep, and over the years you realise you have to work with what people are offering you and slightly unusual rep isn’t done because it’s – well, precisely that, slightly unusual. So I wanted my first Decca album to include lots of French exotic music and you have to do what is popular too - this is the world we live in; I try to do as much as I can on the side. I’ve had several unusual song projects – the last was with Ricky Ian Gordon who’s an American composer, one of my very favourites, I just love him – he did a lot of work in, I want to say Broadway but that’s not really a genre, and he now composes opera done in America, not here, and works with Audra McDonald and Kristin Chenoweth. I immediately responded to his music when I was in Chicago and we did an opera of his called Morning Star in 2002, I loved it from the beginning, so this was a project we’d both wanted to do for a long time. I’ve recorded Mozart now but also a French song album including Ravel’s Shéhérazade with piano rather than orchestra for Delos.

I wanted my trademark at a point in time to be slightly unusual repertoire. That’s why when I was on the Chicago programme I looked for the most obscure rep, and over the years you realise you have to work with what people are offering you and slightly unusual rep isn’t done because it’s – well, precisely that, slightly unusual. So I wanted my first Decca album to include lots of French exotic music and you have to do what is popular too - this is the world we live in; I try to do as much as I can on the side. I’ve had several unusual song projects – the last was with Ricky Ian Gordon who’s an American composer, one of my very favourites, I just love him – he did a lot of work in, I want to say Broadway but that’s not really a genre, and he now composes opera done in America, not here, and works with Audra McDonald and Kristin Chenoweth. I immediately responded to his music when I was in Chicago and we did an opera of his called Morning Star in 2002, I loved it from the beginning, so this was a project we’d both wanted to do for a long time. I’ve recorded Mozart now but also a French song album including Ravel’s Shéhérazade with piano rather than orchestra for Delos.

Ricky Ian Gordon's Langston Hughes setting "Kid in the Park"

French seems to suit you, and it’s a hard language to sing well in.

It rolls off my tongue, maybe not as idiomatically as in my fantasies, but sometimes I think something’s in your blood, maybe somewhere down the line I have some French ancestry – I love the music and the style and I love singing it even if I’m not perfect (below, as Leila in Les pêcheurs de perles).

You strike me as a very truthful singer.

Maybe to my detriment.

But I think the audience immediately sense that honesty. With the Knoxville it was clear from the start. I felt you heard the truth in that.

Oh, I do. For the first time I heard it I cried..

And I did last night - I hadn’t heard the piercing side of it before. There’s the Coplandesque innocence which I don’t always buy into in America, but it’s seen from such a perspective, the childhood memory told by the adult. Both the author, James Agee, and the composer had lost their fathers.

My father died when I was 19, and then I went off to college, and I heard it shortly afterwards, and I think anyone who has a very strong and emotional connection to their childhood feels it – we like to say everyone does, but I’m not sure that’s true, but I did, and to me I think that’s the most emotional part of my life, for others it’s their marriages and their kids, but for me my childhood and that will always bring me to tears if something is referenced in such a way and I can relate to it.

So yours was a happy childhood.

Yes, and what I find most emotional, and it brings me to tears as I’m singing it, is "And who shall ever tell the sorrow of being on this earth, lying on quilts, out on the grass, in a summer evening?". It’s up to you to say, why does he write that, what does it mean? For me, I remember being seven or eight years old and getting very panicked at the notion that something could happen to my parents. "The sorrow of being on this earth" means for me "I love my family so much, and it’s actually painful to love that much, because it’s temporary and you will lose your family one day."

Yes, and what I find most emotional, and it brings me to tears as I’m singing it, is "And who shall ever tell the sorrow of being on this earth, lying on quilts, out on the grass, in a summer evening?". It’s up to you to say, why does he write that, what does it mean? For me, I remember being seven or eight years old and getting very panicked at the notion that something could happen to my parents. "The sorrow of being on this earth" means for me "I love my family so much, and it’s actually painful to love that much, because it’s temporary and you will lose your family one day."

Which is not the kind of thought you often associate with a child. But some very mature philosophical thoughts enter your head at that age…

They do, and people don’t give children enough credit. And that’s the brilliance of the poetry, it’s innocent and yet probably the most wise in its innocence. The prayer to keep the family safe just before those lines is extremely significant for me, because I wasn’t a religious child growing up, and I’m not a religious person now, but I would find myself praying to whatever was out there to keep my parents safe. And I don’t know why I did that, because we were safe, but I always had that in the back of my mind that something could happen. So the prayer to me is that every time I sing that I become an eight-, nine-, 10-year old child, praying.

And it did strike deep last night. All of us who’ve lost our fathers can identify with that, and it triggers the emotions. If you express that directly, people understand.

I hope so. For every artist whatever it is they connect to, the audience will too. And I can’t say it happens every time I sing, some things are really difficult to relate to. Adina for instance - that is hard to relate to, manipulative and petty and very light, not a serious person, it’s a hard one to get into. Musetta too, though she’s got depth beneath.

What other music moves you very deeply?

Traviata for sure, performing Violetta was a very moving experience (pictured right in the Michigan production), the first part of course is theatrics and vocal pyrotechnics, which I feel to a point, but then Acts Two and Three - oh my gosh, if you’re not crying at the end just as a singer…

Traviata for sure, performing Violetta was a very moving experience (pictured right in the Michigan production), the first part of course is theatrics and vocal pyrotechnics, which I feel to a point, but then Acts Two and Three - oh my gosh, if you’re not crying at the end just as a singer…

But that’s a difficulty, isn’t it, for if you’re crying you can’t sing.

Exactly, you’re not doing it right. You pick your times, there are a couple of moments that are not technically very hard in Act Three that you can spend a little more emotion over, but the moment you have to sing some challenging stuff and it gets to you, that’s tough. I know it’s going to be the same with Mimì.

Again there’s truth of the way that part’s written. It is so truthful, anyone who’s been around the deathbed of a dying friend will understand that last scene, it’s not sentimental, it’s true.

That’s right. And I’ve done many Bohèmes as Musetta. In one production, one of the significant lessons we all learned was to avoid at all costs any sentimentality. So for instance when I come up the stairs, telling the men that Mimì has been wandering the streets, she’s seriously ill, please help her, if I come up in tears, no one else is in tears. You have to come up with a sense of OK, we have to get this done, what are we going to do next – even Mimì is not wailing, there are moments when she gets a little bit sentimental, but it’s all forward motion – you move on. It’s the same with Traviata: you sing how you’ve found love, it’s been wonderful, oh no, my God, no wait… You have these moments but it can’t be drenched in tears all the time or the audience is not taken on a journey, and there’s some weird empathy. You’re stealing the audience's tears if you shed your own; if there are tears on the stage there are dry eyes in the house, and vice versa. It’s very strange. But when I cry on stage singing Violetta, it’s at very carefully chosen moments.

What other performances do you especially anticipate from the emotional point of view?

I know the the Four Last Songs are going to make my cry. And Schumann’s Frauenliebe und -leben, which I first sang 15 years ago. When I read the poetry I wasn't impressed, because it’s patronising, but the way the music is written is so simple, the last piece can be a bit morose, but when the theme comes back from the beginning, it’s just like when the theme comes back in Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette, I can’t help it, it brings tears to my eyes. Capuleti I feel but I don’t cry.

You’ve done a fair bit of bel canto – you recorded a rare Donizetti opera, Imelda de’ Lambertazzi, for Opera Rara.

I did, I’ve sung Capuleti twice, lots of Adinas (pictured left), one Norina – I like her even less than Adina! But like I said, I’m branching out into the richer stuff.

I did, I’ve sung Capuleti twice, lots of Adinas (pictured left), one Norina – I like her even less than Adina! But like I said, I’m branching out into the richer stuff.

Mozart to Strauss seems like a natural progression. You’d make a wonderful Marschallin…

I’m a good age for the Marschallin right now. We just need to find a 15-year-old Sophie and we’re set! Strauss will probably make me cry. There’s so much emotional, wonderful music, you just have to be selective about when you can let your emotions go. The other wonderful thing about the Knoxville is that it’s all written in, those moments just fall naturally. It is a masterpiece, it shows every facet – slow, fast, dramatic, soft, moving. It’s one of my favourite pieces. And I hope to sing it until the day I die, I really do.

So it would be a desert island disc?

Oh, yes.

What singers would you choose?

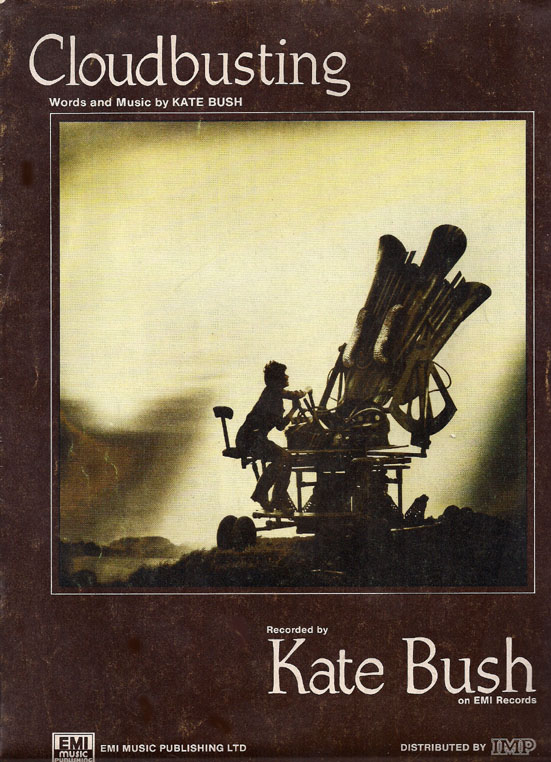

I probably wouldn’t choose a lot of opera because I do it for a living. Stevie Nicks is my absolute favourite, and I love Kate Bush.

She’s making a comeback here soon.

She’s a genius. I think if one day I could do a sort of Anne Sofie von Otter Abba-esque project I would do a Kate Bush tribute.

But you would take her songs and make them yours?

Yes, I’d take it and have somebody else hopefully collaborate on creating something unique and influenced by Kate Bush but not an imitation. Cloudbusting I would like to do because it’s sort of orchestral, with the cellos and all, but the way it’s written you could possibly get away with doing something like that. But it would have to be perfect, because you can’t mess with Kate. But yes, mmm, desert island singers...

Yes, I’d take it and have somebody else hopefully collaborate on creating something unique and influenced by Kate Bush but not an imitation. Cloudbusting I would like to do because it’s sort of orchestral, with the cellos and all, but the way it’s written you could possibly get away with doing something like that. But it would have to be perfect, because you can’t mess with Kate. But yes, mmm, desert island singers...

Or even singers who influenced you when you were younger, were there any role models?

I always loved Loreena McKennitt, any Celtic connection…you know Clannad is a band that I discovered maybe five or six years ago, and I have all their records now, every number that they’ve done, so they’re a desert island band for me too. I guess in terms of classical singers you can’t go wrong with Freni…

It’s amazing the number of sopranos who choose Freni as an example of long-term vocal survival.

She is amazing. And she was so free, and also so vulnerable as an artist. There was no pretence. As a technician and an artist I would probably choose Scotto.

It was only recently I actually watched her performances as well as listened to her CDs. She’s not mannered but very stylised.

Exactly, I don’t think it was affected or mannered, but you could tell that she knew exactly what everything was going to be – but it was never boring, some people do that and it’s clinical. I think in her case she came to those conclusions because they made sense, they were on purpose, and when she executes them it’s with 100 percent commitment. So it’s not going through the motions like a puppet: for her it was quintessential artistry and just perfect technique.

I think my favourite recording of a soprano singing an Italian aria is Scotto in Suor Angelica’s "Senza mamma". I’d even choose that over Callas.

Have you heard her Elisir with Carlo Bergonzi? If you want to hear the perfect singing, that’s it: she's not a cute Adina but a very sophisticated one. That’s the kind of perfection we all have to aspire to.

Add comment