theartsdesk Q&A: Mezzo-soprano and Director Brigitte Fassbaender | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Mezzo-soprano and Director Brigitte Fassbaender

theartsdesk Q&A: Mezzo-soprano and Director Brigitte Fassbaender

A great singer and musical force for the good talks about opera from two sides and Lieder

The mezzo-soprano Brigitte Fassbaender, who will be 75 on Thursday 3 July, was unsurpassed for dramatic impact and presence in roles such as Octavian in Der Rosenkavalier and Prince Orlofsky in Die Fledermaus, during a singing career which spanned from the early 1960s to the mid-1990s.

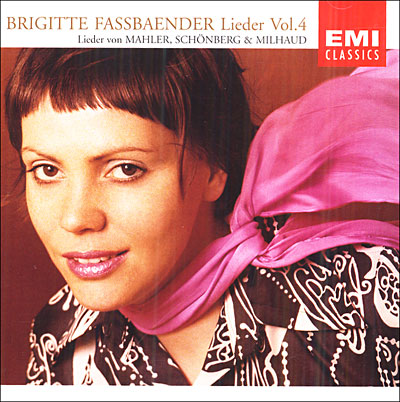

Her command of the long lines of Mahler's songs, and the immediacy and understanding she brought to Lieder generally placed her in the very top flight of interpreters alongside Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Peter Schreier and Christa Ludwig.

She stopped singing almost two decades ago, and has since forged a career as opera director. I interviewed her at the Wigmore Hall immediately after the first of her two March 2014 masterclasses, in which she was teaching German Lieder to postgraduates from the UK music colleges. Her stamina, energy and purpose that afternoon were those of a quite incredibly youthful 75-year-old.

We wish her a very happy birthday (a young Fassbaender left as Octavian with silver rose).

We wish her a very happy birthday (a young Fassbaender left as Octavian with silver rose).

SEBASTIAN SCOTNEY: You have described your decision to stop singing as “not wanting to grow old on stage”. And there were stages in it?

BRIGITTE FASSSBAENDER: My last role on stage was Klytemnestra [in Strauss's Elektra] at the Met. But then I went on singing Lieder for two years until the end of 1994. I said farewell to the opera to concentrate on Lieder. But nobody knew that it was the farewell, not even I, the decision happened later.

From 1999 to 2012 you were Intendant of the Tiroler Landestheater in Innsbruck?

At Innsbruck we had 24 singers, the largest ensemble in Austria. With some of them, they were beginners on their first engagement. I made demands, but also furthered their careers. You could build them up and let them mature. As personalities and as singers. You need more than a voice.

Every role [in Innsbruck] was double cast, they could regenerate and help each other. They were protected, I didn't ask for difficult stuff from young voices. It was wonderfully creative to work with a young and talented ensemble. It was also a contract where I had to direct two productions a year. That was also good, and important [for me] to develop in doing this. Although we were two leaders of the business, at the end of the day I had overall responsibility. Everything difficult lands on your desk.

The Intendant job in Innsbruck has finished, right?

Yes. That finished in 2012. And I'm now I'm free. Freelance [laughs]. Free to do other things. I'm still busy directing in theatres all over Germany. And masterclasses. I'm doing new productions, masterclasses. I just did Albert Herring in Vienna. I'll be directing Rigoletto in a small but very good opera house in Germany. A Bohème. There is Rosenkavalier with Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic. It will be nice to do that, difficult because time will be short, but I think I know the piece quite well. [Laughs]

Fassbaender with Lucia Popp in the final scene from Der Rosenkavalier conducted by Carlos Kleiber

And I wrote two libretti for musicals. I love doing it, working with a young German composer Stefan Kanyar – we wrote Lulu together, a musical with a very exciting plot. The next one was Shylock, based on The Merchant of Venice. We are thinking about a third because all good things come in threes. We don't know exactly what we want to do, whether it should be another musical, an opera. I'm keen to do another one because it is challenging and wonderful work.

And you are writing an autobiography?

No. My life is not important enough to write a huge book about it.

But you told one interviewer a first chapter was written?

Yes, yes, I started. It's so difficult and I don't have time. And singers' biographies always end up showing just the good reviews. They are boring and have nothing to do with the real life a singer has to come through. If I write something it will be more a memoir, something to do with my family. My father's life [Willi Domgraf-Fassbaender was a distinguished baritone and can be heard on the early Glyndebourne recording of Le nozze di Figaro] is quite interesting, mine is not interesting. It's difficult, such a lot happens.

The world for singers must have changed a lot since your first operatic role as Fourth Page in Lohengrin in Munich in 1961?

Yes it has, but not in the crucial moments for a singer. Essentially a singer's life stays the same.

But singers now have an uncertain life ahead of them. The security of being in an ensemble in the theatres is not there. Ensembles have been destroyed by financial situation everywhere. It's a horrible thing. [As for the singers], they risk less and less. They want to sing as beautifully, as perfectly as possible. They don't allow themselves to be totally free and open, either with themselves or with the public. That is a barrier you have to jump over. It takes time, but you have help them to jump over it.

From what I saw this afternoon, your method, mixing praise and criticism seems to work miracles, and you work a lot on breath control

I'm not a teacher who destroys, I always want to build up (right, directing Andreas Mitschke and Alexander Trauner in the Vienna Albert Herring, photo by Barbara Pálffy). Praising is always helpful. The master class, in front of the public, is a difficult situation for these young singers to show weakness. This kind of work that is based on trust for each other, on respect for what the other does. It always ends up with me giving them some technical advice. [As regards breath control] I think there is nothing more important than that a singer should know how to work with the breath. Not many singers really know about that, I always feel, especially not the students. This is always the main work I have to do. When you come across emotions and totally natural feelings [in a singer] then it's probably easier.

I'm not a teacher who destroys, I always want to build up (right, directing Andreas Mitschke and Alexander Trauner in the Vienna Albert Herring, photo by Barbara Pálffy). Praising is always helpful. The master class, in front of the public, is a difficult situation for these young singers to show weakness. This kind of work that is based on trust for each other, on respect for what the other does. It always ends up with me giving them some technical advice. [As regards breath control] I think there is nothing more important than that a singer should know how to work with the breath. Not many singers really know about that, I always feel, especially not the students. This is always the main work I have to do. When you come across emotions and totally natural feelings [in a singer] then it's probably easier.

This is important for you because in your own career you have had moments of self-doubt?

Absolutely. Not moments, life-long self doubt. But this belongs with it. You must never feel content with yourself. If you feel like that you should go to bed and stay there.

But were you always confident as a recitalist?

No, I needed someone to make me awake for the stage. I was very shy. It took me a long time before I could open myself to the public. It's a long journey, You feel everything, but....

What made the difference?

I don't know. Probably working together with a great accompanist. That makes you secure. It was Irwin Gage. I felt the first serenity in working with Irwin. Erik Werba was a wonderful accompanist, but you never felt free, you never escaped from that atmosphere of respect. With Irwin we were at the same eye level. One could feel free, innovative.

But there are a lot of flexible accompanists around?

Yes, but I have always liked to work with a strong accompanist, not just with someone who follows you. It was essential for me to have a real partner onstage. Like Wolfram Rieger. We grew up together. I discovered him at the Hochschule in Munich.

Brigitte Fassbaender sings Mahler's "Rheinlegendchen" in 1979

In Lieder, your way of setting the scene for each song was always something very special.

You need an enormous helping of fantasy, intuition and imagination, you also have to have a very strong idea what you want to say about the song. These are always individual feelings, but it was always important for me to have a strong inner picture, that I saw absolutely what happens in he song. Colours and atmosphere and smells and taste, an immediate association.

And spontaneity?

I hope so. I can't explain it. It happened. What I knew was that something else always happened [in performance].

Can you teach stage presence?

No, actually not. You can teach, encourage to give everything, you can develop it, but charisma and stage presence - which are the same thing - you can't teach. You must have it. I never knew where it came from.

With your father an opera singer and your mother an actress could some of it have been inherited?

With your father an opera singer and your mother an actress could some of it have been inherited?

Maybe. I don't want to know, I'm just like I am, and don't think about it.

You have worked with mightily charismatic characters. You've described Carlos Kleiber as a powder-keg?

In a way he was. You never knew what was going to happen in the next moment. He was a real genius. If characters like that are around now I don't know them. I hope they don't die out.

And you must have been affected by the death of Fischer-Dieskau?

It was really hard, because I loved him. He was a wonderful artist. Irreplaceable. He shaped our whole generation, with his fantastically imaginative programmes.

Your visits to London are rare, but you do like where we are today, the Wigmore Hall, right?

It's the most wonderful concert hall in the world. The best acoustic ever. One of the nicest atmospheres. A wonderful size. Intimate but generously proportioned. And with the nicest public. They are the most educated audience I have ever met. They know about the music and what they want to hear, very polite and warm-hearted. They stay at a healthy distance and don't want to take possession of you. You can feel they like you, they help you, they carry you. I have wonderful memories of this concert platform.

- In an extract from the March interview, Fassbaender remembers the circumstances of her first ever recording, playing the mother in the duet "Heinerle, Heinerle, hab' kein Geld" from the operetta Der fidele Bauer by Leo Fall

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Comments

I toast this wonderful

I toast this wonderful artist, who comes across as such a Mensch in this interview, on her 75th birthday, which I shall honour by listening to her Orlofsky and finally getting round to reading the chapter on her in Terry Castle's 'The Apparitional Lesbian'.

Fine article on this great

Thank you for the compliment.

Thank you for the compliment. This interview could not have been done without the facilitation of the kind folk at Wigmore Hall; it was done when she was doing masterclasses there and they may be able/willing to forward a request. Hope this helps.