Karajan's Magic and Myth, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Karajan's Magic and Myth, BBC Four

Karajan's Magic and Myth, BBC Four

John Bridcut explores the many contradictions of the superstar conductor

There have been legendary conductors, and then there was Herbert von Karajan. He was a colossus of post-World War Two classical music, equipped with fearsome technical mastery allied to a vaguely supernatural gift for extracting exquisite sounds from orchestras. But that wasn't all. An expert skier with a passion for high-performance cars and flying his own jet, he was as charismatic as a movie star or sporting idol.

John Bridcut's superb profile surveyed the Salzburg-born Karajan as if he were Mont Blanc or the Matterhorn, considering the contradictions in his character as though studying aspects of the landscape at different times of day amid changing weather conditions. Monomaniacal and power-crazed, or a generous collaborator with esteemed colleagues? A self-obsessed narcissist, or a dashing man of the future with a vision of how new technology could transform the public's understanding of music? An artistic genius, or a gifted actor playing the part of one?

There could be no single answer, but the fact that Karajan, who died 25 years ago, remained an impenetrable enigma was a powerful ingredient of his allure. Enraptured by his own mythology, Karajan protected his privacy obsessively. This film interviewed a long roll-call of his collaborators and professional partners, but none claimed to have known Karajan well. If the conductor had close friends, nobody knew who they might have been (Karajan with his third wife Eliette Mouret, pictured above).

There could be no single answer, but the fact that Karajan, who died 25 years ago, remained an impenetrable enigma was a powerful ingredient of his allure. Enraptured by his own mythology, Karajan protected his privacy obsessively. This film interviewed a long roll-call of his collaborators and professional partners, but none claimed to have known Karajan well. If the conductor had close friends, nobody knew who they might have been (Karajan with his third wife Eliette Mouret, pictured above).

Karajan's early professional success in Germany coincided with the rise of Nazism, and the fact that he joined the Nazi party in 1933 has been used as a stick to beat him with. The evidence suggests he did this for personal self-advancement rather than from ideological zealotry, and his second wife Anita, who he married in 1942, was considered one-quarter Jewish under the regime's arcane rating system. But perhaps this sliver of darkness lent a dash of Mephistopheles to the Karajan myth.

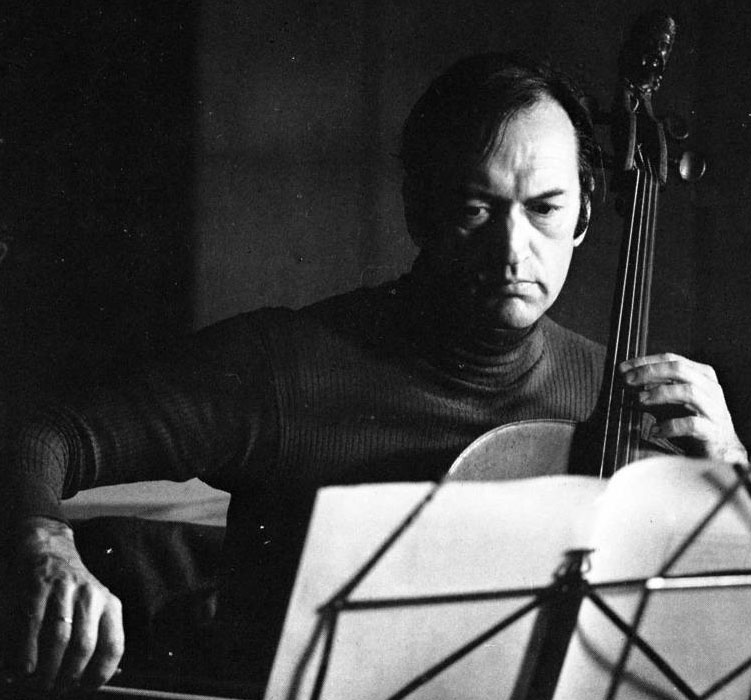

Much of the enjoyment of Bridcut's film, apart from the footage of Karajan conducting Strauss's Don Juan or Mahler 5 or Jessye Norman singing Wagner's Liebestod, came from the fascinating range of characters he'd rounded up for interviews. Veterans of the Philharmonia Orchestra from the 1950s remembered the impact of the slender, charismatic conductor ("he was sort of sexy somehow," said violinist Kathleen Sturdy). Sir Mark Elder analysed clips of Karajan in rehearsal, as he tweaked microscopic nuances of tone. Conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt, formerly a cellist in the Vienna Philharmonic (pictured above), recounted a chilling tale of how Karajan made a faltering violinist stand up during rehearsals and play his part solo, then ordered him out and had him dismissed. Violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter, nurtured by Karajan as a teenage prodigy, praised his supportiveness as a conductor, then recalled how his daredevil attitude to flying made her, and everyone who flew with him, sick.

Much of the enjoyment of Bridcut's film, apart from the footage of Karajan conducting Strauss's Don Juan or Mahler 5 or Jessye Norman singing Wagner's Liebestod, came from the fascinating range of characters he'd rounded up for interviews. Veterans of the Philharmonia Orchestra from the 1950s remembered the impact of the slender, charismatic conductor ("he was sort of sexy somehow," said violinist Kathleen Sturdy). Sir Mark Elder analysed clips of Karajan in rehearsal, as he tweaked microscopic nuances of tone. Conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt, formerly a cellist in the Vienna Philharmonic (pictured above), recounted a chilling tale of how Karajan made a faltering violinist stand up during rehearsals and play his part solo, then ordered him out and had him dismissed. Violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter, nurtured by Karajan as a teenage prodigy, praised his supportiveness as a conductor, then recalled how his daredevil attitude to flying made her, and everyone who flew with him, sick.

At his peak, Karajan's recordings accounted for 10 per cent of the global classical market, and for many listeners, "classical music" meant the discs he recorded on Deutsche Grammophon with the Berlin Philharmonic. But in his later years his behaviour grew more egocentric. He shamelessly milked encores for personal gratification, and embarked on a campaign of videotaped orchestral recordings with his company Telemondial, designed to showcase the God-like attributes of the Maestro. Former Berlin Philharmonic flautist James Galway (pictured above) had some fabulous anecdotes about how Karajan would force bald musicians to wear wigs for the filming, and then not show their faces anyway. Karajan disliked Galway's dishevelled beard, so while listeners heard Galway on the soundtrack, he was replaced on camera by the clean-shaven flautist Andreas Blau. Karajan made sure the audience couldn't misbehave by using life-sized photographs instead of people.

At his peak, Karajan's recordings accounted for 10 per cent of the global classical market, and for many listeners, "classical music" meant the discs he recorded on Deutsche Grammophon with the Berlin Philharmonic. But in his later years his behaviour grew more egocentric. He shamelessly milked encores for personal gratification, and embarked on a campaign of videotaped orchestral recordings with his company Telemondial, designed to showcase the God-like attributes of the Maestro. Former Berlin Philharmonic flautist James Galway (pictured above) had some fabulous anecdotes about how Karajan would force bald musicians to wear wigs for the filming, and then not show their faces anyway. Karajan disliked Galway's dishevelled beard, so while listeners heard Galway on the soundtrack, he was replaced on camera by the clean-shaven flautist Andreas Blau. Karajan made sure the audience couldn't misbehave by using life-sized photographs instead of people.

It was hardly surprising that the Berlin Phil eventually fell out of love with their increasingly dictatorial supremo, though their rejection seemingly hurt Karajan deeply. He found succour with the Vienna Phil, and Placido Domingo remembered a performance they gave of Bruckner's 8th symphony in New York, not long before Karajan's death. He recalled "a religious feeling, adoration, and at the same time kind of nostalgic, like an end of an era." As indeed it was. There were "not many in this world like him," commented the conductor's devoted personal assistant Lore Salzburger.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

will this programme be