Deep pain and sadness expressed through intense creative discipline aren’t qualities noted often enough in the music of Sergey Rachmaninov. Yet they’ve been consistently underlined, with rigour to match, in Vladimir Jurowski’s season-long “Inside Out” festival with his London Philharmonic Orchestra playing at a consistent white heat. Last night’s typically singular finale was crowned by a performance – Jurowski’s first – of the enigmatic Third Symphony as far removed as you could imagine from “tinsel”, a term with which it found itself bizarrely associated alongside lighter pieces in a Guardian article about the Proms earlier this week.

Few Jurowski programmes, even with Rachmaninov at their heart, are penny-plain overture-concerto-symphony formats, and this was no exception. In a first half of spellbinding orchestral transcriptions, he managed to pay two further homages. One was to Yury Butsko, of the back-to-folk-roots generation which also included Shchedrin and Sviridov; Butsko died three days before the concert. His arrangements of four early piano pieces - one solo, three four-hand – began with Rachmaninov’s homage to the “Slava” folk song most famously treated in the Coronation Scene of Boris Godunov; Rachmaninov manages to outdo former celebrants Musorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky by throwing every harmony and style at it he can think of.

At the other end of the sequence, there was orthodox chant and an ostinato bell-song in the “Easter” movement of the brilliant First Suite for piano duet which, as Jurowski observed in a pre-performance talk valiantly conducted with a heavy cold, is a striking progenitor of Minimalism. (My own observation is that if you play the opening of the "Alarm Bells" movement in the Rachmaninov work which Jurowski regards as his richest, the “Choral Symphony” The Bells, an unwitting listener might attribute it to John Adams). Butsko’s arrangements, with ample percussion and piano, sounded closer to Stokowski’s outlandish, often rough orchestration of Musorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition than to Ravel’s.

At the other end of the sequence, there was orthodox chant and an ostinato bell-song in the “Easter” movement of the brilliant First Suite for piano duet which, as Jurowski observed in a pre-performance talk valiantly conducted with a heavy cold, is a striking progenitor of Minimalism. (My own observation is that if you play the opening of the "Alarm Bells" movement in the Rachmaninov work which Jurowski regards as his richest, the “Choral Symphony” The Bells, an unwitting listener might attribute it to John Adams). Butsko’s arrangements, with ample percussion and piano, sounded closer to Stokowski’s outlandish, often rough orchestration of Musorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition than to Ravel’s.

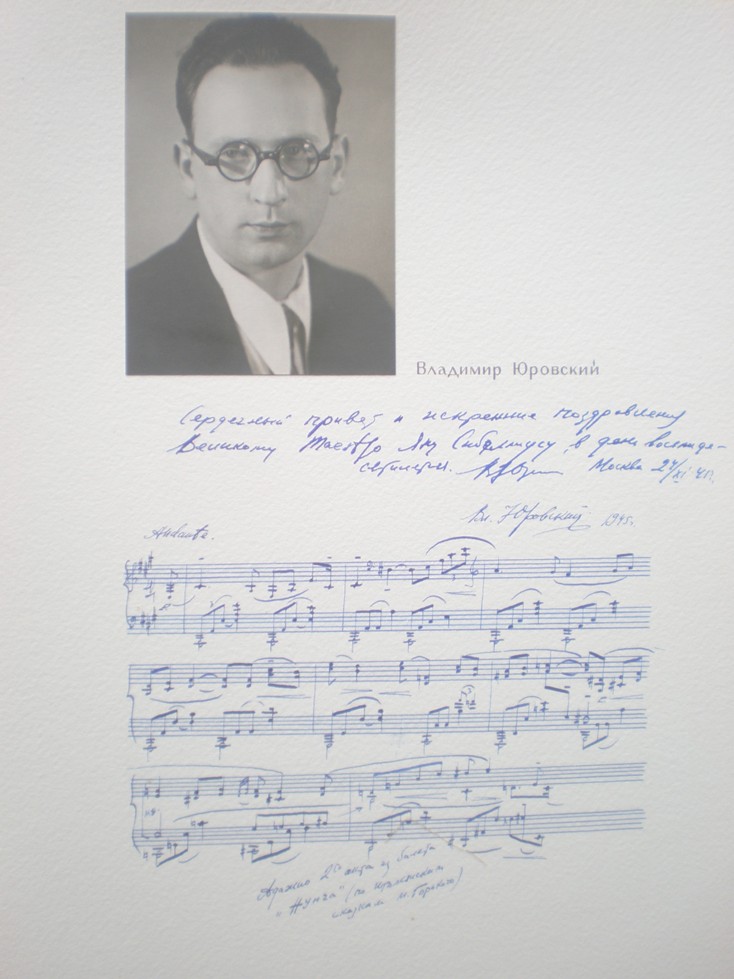

The other homage was to Jurowski’s grandfather, also Vladimir, a well-respected Soviet-era composer whose 100th anniversary we were marking; strange to think he was born in the year Scriabin died (pictured above: a homage from Jurowski the composer to Sibelius on his 80th birthday, unearthed during the author's research at Sibelius's house-museum, Ainola). His arrangements of 10 Rachmaninov songs – a sphere in which it becomes ever more obvious the composer excelled as much as in any other – were made for one of the two great Russian tenors of the mid-20th century, Ivan Kozlovsky, a less sweet voice than his rival Sergey Lemeshev but a perfect inflector of his native language.

This made Vsevolod Grivnov (pictured below by Kirsten Loken Anstey) the ideal choice for the sequence. Standing without a score, conducting himself with his right hand, Grivnov was perfectly able to scale down his heroic tenor to poetic slivers of sound in fugitive visions like “The little island” and “Sleep” – for me one of the greatest songs of all time, up there with Schubert and Mahler in the amazing harmonies and hypnotic effect Rachmaninov uses to conjure Sologub’s transcendent verses.

The elder Jurowski's orchestrations are mostly subtle, paying Rachmaninov clear homage in the disconsolate violas which sympathise with the outsider at the Russian Orthodox service in “Christ is risen!” and reduced to chamber proportions, with the grandson further cutting back the number of strings, in the pessimistic musical realization of Sonya’s “We shall rest!” speech at the end of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya (wouldn’t it be good to get a number of contemporary Russian composers to give their responses to this ambiguous curtain?). Ten songs might seem rather a lot, but many finish before you want them to, and despite persistent applause between numbers, Grivnov and Jurowski held the tearful alternation of bitter and sweet to absolute perfection, a real marriage of voice and instruments.

The elder Jurowski's orchestrations are mostly subtle, paying Rachmaninov clear homage in the disconsolate violas which sympathise with the outsider at the Russian Orthodox service in “Christ is risen!” and reduced to chamber proportions, with the grandson further cutting back the number of strings, in the pessimistic musical realization of Sonya’s “We shall rest!” speech at the end of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya (wouldn’t it be good to get a number of contemporary Russian composers to give their responses to this ambiguous curtain?). Ten songs might seem rather a lot, but many finish before you want them to, and despite persistent applause between numbers, Grivnov and Jurowski held the tearful alternation of bitter and sweet to absolute perfection, a real marriage of voice and instruments.

Jurowski had told us that he didn’t begin to understand the Third Symphony until he heard the composer’s own interpretation – one of only three recordings of Rachmaninov as conductor – and then only by listening again and again. His own reading had equal flexibility, but a very different approach in emphasising the depths and making time stand still. Easier to do by ignoring, like the composer-conductor, the first movement’s exposition repeat; the drama surged achingly forward, the big melodies unfolded mesmerically with necessary portamenti, the slides between notes, but no hint of Hollywood splurge. Rachmaninov was writing for the famous Philadelphia strings of the 1930s, but he exposes violins rather than indulges them in a surprisingly lean work where no player can get away with a lazy phrase.

The LPO sound was as magnificent in fullness as it was haunting in the twilight zones, with excellent work from principal horn John Ryan, oboist Ian Hardwick and cor anglais player Sue Böhling. Jurowski even made a virtue out of a certain irresolute quality in the structure of Rachmaninov’s finale, alternately ferocious and lost, with a hair-raising coda based on the composer’s obsession with the Dies Irae or Latin “day of wrath” chant full of demonic associations. Usually the symphony ends in a glittering cannonade; this was a dance of death until the end, razor-sharp in precision but still overwhelmingly exciting in its impact. Rachmaninov as one of the 20th century's truly great and serious composers? Unquestionably.

Add comment