10 Questions for Composer Ludovico Einaudi | reviews, news & interviews

10 Questions for Composer Ludovico Einaudi

10 Questions for Composer Ludovico Einaudi

What are the elements that make up Einaudi's music?

Last month, Ludovico Einaudi's album Elements debuted at No 12 on the UK album charts, which made it the highest-charting modern classical album since Henryk Górecki's Symphony of Sorrowful Songs reached No 6 in 1992. It was proof of the quietly burgeoning allure of Einaudi, which has been stealthily expanding around the world since his first solo release, 1988's Time Out.

Subsequent albums such as Le Onde, Eden Roc and I Giorni have lodged several of his limpid and haunting compositions in the ether, whence they might descend to be played on radio, or heard in commercials or on movie soundtracks. His music has been a constant thread in Shane Meadows's This Is England, in both its movie and TV incarnations, has been heard in numerous Italian films, and was used in Casey Affleck's I'm Still Here and in the French box office hit Intouchables. His album In a Time Lapse (2013) added layers of electronica to Einaudi's habitual piano-based compositions, lending the album a tincture of modernity which prompted a splurge of download sales.

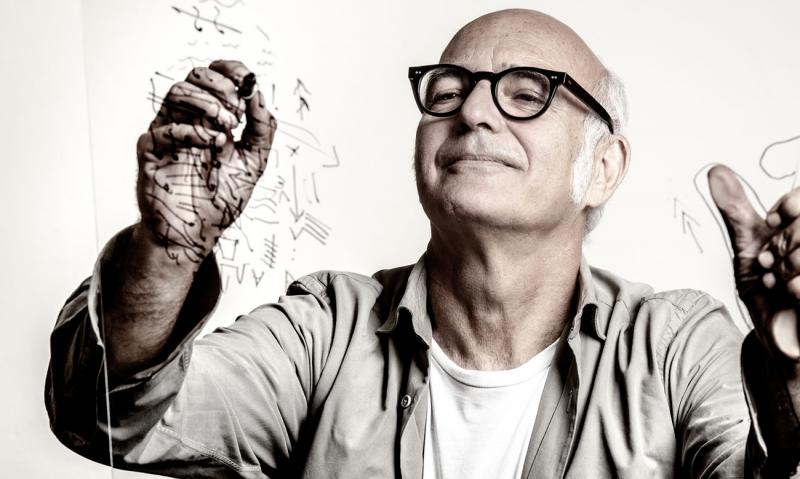

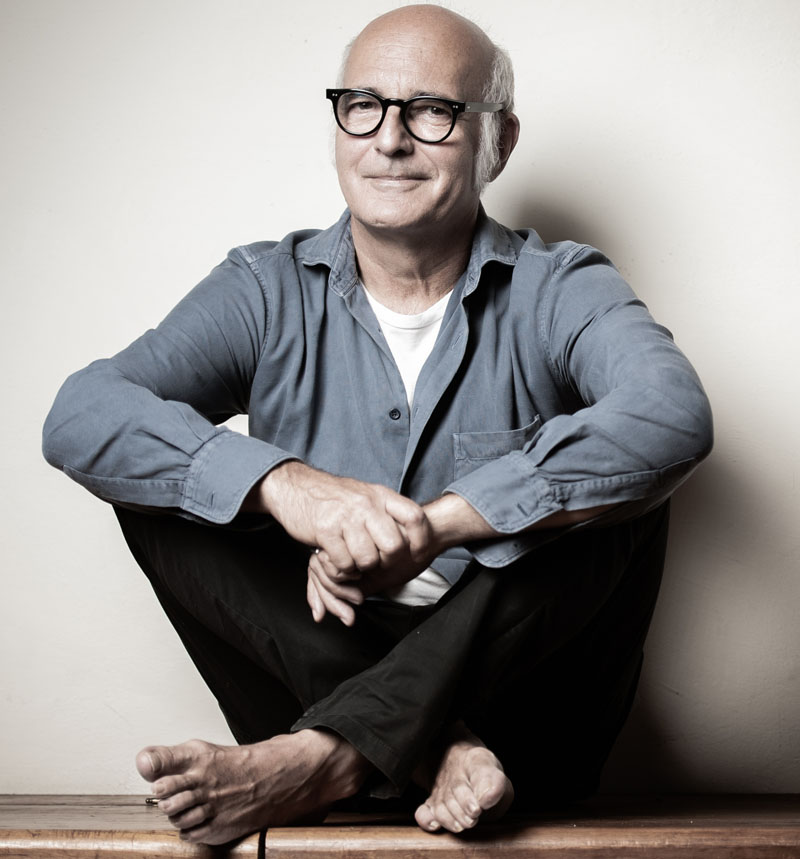

With his domed head and "intellectual" spectacles, Einaudi radiates a scholarly air, appropriate for a man who studied with the revered avant-gardist Luciano Berio and spent the early part of his career grappling with the arcane demands of serialism. He has a fascinating background. He's the grandson of Luigi Einaudi, the first post-World War Two president of Italy, whose speeches provided the raw material with which Ludovico's father, Giulio, launched his own publishing company, Giulio Einaudi Editore (which also published Primo Levi and Italo Calvino). Meanwhile Ludovico will often retreat to the family vineyard in Piedmont, Poderi Luigi Einaudi, when he needs a bit of chill-out time. His mother was a talented amateur pianist and the daughter of a composer and conductor, and he credits her with instilling in him a love of the piano.

With his domed head and "intellectual" spectacles, Einaudi radiates a scholarly air, appropriate for a man who studied with the revered avant-gardist Luciano Berio and spent the early part of his career grappling with the arcane demands of serialism. He has a fascinating background. He's the grandson of Luigi Einaudi, the first post-World War Two president of Italy, whose speeches provided the raw material with which Ludovico's father, Giulio, launched his own publishing company, Giulio Einaudi Editore (which also published Primo Levi and Italo Calvino). Meanwhile Ludovico will often retreat to the family vineyard in Piedmont, Poderi Luigi Einaudi, when he needs a bit of chill-out time. His mother was a talented amateur pianist and the daughter of a composer and conductor, and he credits her with instilling in him a love of the piano.

He began his musical studies in Turin, where he was born in 1955, before moving on to the Conservatorio di Musica G. Verdi in Milan, where he earned a diploma in composition. A subsequent spell at Pierre Boulez's wacky IRCAM sound laboratory in Paris brought him into Berio's orbit. Though he coached Einaudi in 12-tone composition, Berio (who liked to amuse himself by arranging Beatles songs) also urged him to take a broader view of music. Einaudi had been introduced to Bob Dylan, The Beatles and the Stones by his two elder sisters, and has recalled how "when I was a teenager I travelled in Italy and England, and I had a chance to listen to bands like The Who, The Yardbirds and Pink Floyd. I've always continued to listen to new developments in rock music, because I think it's a very creative world." His ability to pluck ideas from pop, classical, minimalist and African music has rendered his work distinctive yet indefinable – just call it "Einaudi music".

ADAM SWEETING: How does music come to you? Do you hear a musical theme in your mind, or is it more about creating a feeling?

LUDOVICO EINAUDI: Melody, and harmony, is a mystery, and in a way it is about memory, and a capturing and channelling of time, and what has gone before. It definitely grabs your attention by instantly taking you somewhere else, to another place, another time, one you may never have actually experienced, or one that is unique to you. I love to explore melody. A great melodic line is like a person’s soul, and coming up with an original melody, it can be like you are illustrating the soul. People look at you like you are a magician. You have conjured up something out of nowhere that no one has before. You are creating a route to the soul. I think it is because the world is so fast and disposable, and more and more people are looking for an extension of lost privacy, something which can help create a personal space. It can become important in their lives, because they sense it is made with a certain level of integrity. The music is itself a metaphor for the idea of reflection, patience, privacy, prayer, of the internal. The internal that can become the eternal. It is saying it and being it.

Do all your compositions begin at the piano?

Do all your compositions begin at the piano?

I have different approaches when I compose. Sometimes it is sitting at the piano, other times I work with my computer with sounds and samples.

Were there particular events or ideas that inspired the new pieces on Elements? For instance "Song for Gavin"?

The more I go on, the more I demand of myself. My next project must always compel me to do more, to climb a new mountain, arrive somewhere I have not been before. It, the view if you like, must seem new, at least to me. On my new album I researched centuries of ideas about the elements as the constituents of all matter with the aim of challenging my brain and then channelling all this knowledge into the music. Transferring scientific and philosophical thoughts into sound, finding music in hidden, noiseless places. I also wanted to challenge those who might think they know my work and think that this would be again, for better or worse, more of the same.

I wanted this record to be both more intriguing to me, and to those that like listening to me. Obviously by me but with added... elements. Sometimes the titles come first, sometimes second; a title can grow from the music, or the music from a title. They contain information and clues about the music, but I don’t want to give anything away. The title means you listen to it differently than you would if they were just dry numbers and the key. They’re invitations, I think it was something else I learned from Berio. He liked titles, rather than merely saying "sonata" or "prelude", and he was very precise about them, so that they were themselves musical, a little poetic, or in their own way the beginning of the piece. To set you in motion. The first note or the first chord. It pushes you in one direction or another. "Song for Gavin" itself is a piece I wrote in memory of the wonderful songwriter and friend Gavin Clark [of Sunhouse, Clayhill and Unkle], who I met whilst working with Shane Meadows on "This Is England".

Your music has been used throughout the history of "This Is England", and recently appeared in "This Is England '90" on Channel 4. Do you think this has had a big effect in bringing your music to a wider audience in Britain?

Your music has been used throughout the history of "This Is England", and recently appeared in "This Is England '90" on Channel 4. Do you think this has had a big effect in bringing your music to a wider audience in Britain?

Shane Meadows is a genius of filmmaking, for me in a similar category to Martin Scorsese, and it has been a real pleasure and privilege to work with him on "This Is England". I hope that it has given people a route into my music. It is fantastic when you write a piece of music that touches so many people. It is very satisfying because you have collected a group of emotions into one place and then see it travel so far. You cannot really answer any questions about the music, because it has become something else, in the ears and mind of the listener. It is gratifying that people identify with the music, but it has gone beyond my understanding. The combination of the music and the listeners’ feelings about the music are not something you can really talk about. It’s more than a mystery. It is a mystery that is always changing shape.

In your work, you seem to have found a way to blend acoustic and electronic instruments so that it's often difficult to tell which is which. Have you been inspired by a composer such as Penderecki, who is able to find new sounds from conventional instruments?

For me it's about how you imagine the combination of colours in a composition. I like to establish relations between sounds to create more complex sound textures and depth. For example you can add to a low pizzicato note of a cello, another sound made with a low drum or with an electronic instrument. And so on, you can apply this to any layer of the music. This is a basic rule for orchestration anyway, and I like to involve electronic sounds in it.

How did you achieve the ticking-clock effect in your piece "Twice"?

That sound is made with a marimba played with brushes.

When you play a solo recital at the piano, how do you compensate for the other instruments from the recording not being there?

Well, of course, you have to play very differently, but I enjoy the nakedness of the solo piano and the idea that you have to search for the fundamentals of the compositions.

Are you involved with more soundtrack work? Is this an area that is important to you?

Are you involved with more soundtrack work? Is this an area that is important to you?

I am about to go on tour with Elements so I am busy in rehearsals, but, yes, I will be working on more film soundtracks. I find the artforms of film and music to be complementary. A well-made soundtrack can multiply the emotion of a film scene and I get great pleasure from working with some wonderful filmmakers.

You have a strong interest in World and folk music, and you are now director of the La Notte della Taranto festival in southern Italy. How did your Taranta Project album come about? It mixes Turkish, African and Italian music and electronics very successfully.

I was invited to be director of the Notte della Taranta festival in 2010 and 2011. I love this passionate rhythmical folk music of the Salento region so I invited various of my friends (Ballake Sissoko, Justin Adams, Juldeh Camara, Mercan Dede) to come along and contribute alongside local musicians from the South of Italy (Mauro Durante, Antonio Castrignano, Enza Pagliara, Alessia Tondo). I took the basic rhythmical nature of the Taranta and some beautiful ancient melodies and I started to arrange and compose, adding influences from other musical cultures to create something new and hopefully exciting. We took the sound of the festival on tour in 2012 and I released the album Taranta Project earlier this year, which captures the essence of the sound we achieved. It sounds like a studio album but with the energy of a live performance. My idea was to bring this music to a more universal level connected to other traditions.

I know you're a fan of rock music, and sometimes I think I hear echoes of U2's guitarist The Edge in some of your pieces, for instance "Eden Roc" and "I Giorni". Would I be right?

I don't know specifically about the piece "I Giorni", but I love The Edge's guitar style, it is unique. There is an ancient world resonating in his guitar sound.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment