theartsdesk Q&A: Pianist Boris Giltburg | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Pianist Boris Giltburg

theartsdesk Q&A: Pianist Boris Giltburg

Russian-Israeli master on Prokofiev, Rachmaninov, competitions and pianos

London has been missing out on Boris Giltburg for too long. He's been playing Shostakovich concertos back to back with Petrenko in Liverpool, and the big Rachmaninov works up in Scotland (see theartsdesk's review today of the latest Royal Scottish National Orchestra programme).

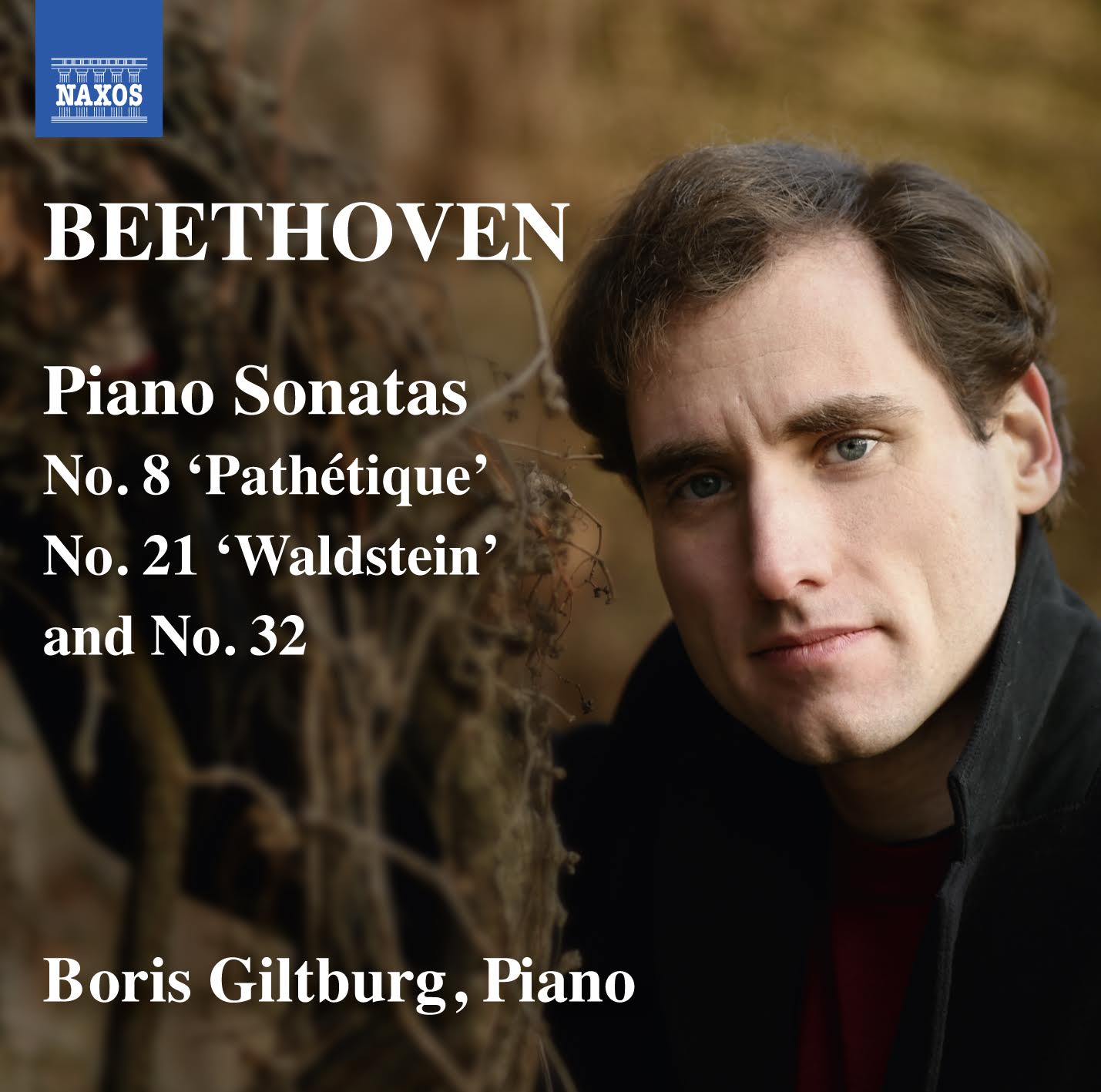

I spoke to Giltburg just after his Queen Elizabeth Hall recital of Rachmaninov's Op. 23 Preludes, Prokofiev's Eighth Piano Sonata, an elaborated version of Ravel's own transcription of La Valse and several breathtaking encores. Since then he's released two discs on Naxos, one of ineffable Schumann, the other of Beethoven sonatas much admired by Graham Rickson in his classical roundup.

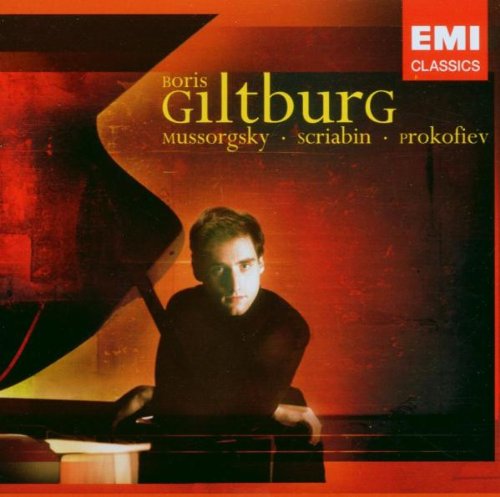

DAVID NICE: You included the Prokofiev Sonata back in 2005 on your EMI debut disc. How do you think your attitude has changed to it over the years?

DAVID NICE: You included the Prokofiev Sonata back in 2005 on your EMI debut disc. How do you think your attitude has changed to it over the years?

BORIS GILTBURG: My perspectives on music and performance generally changed quite a lot. I've probably changed more in the last two years than the previous 10.

Any reason for that?

The main reason was the Rubinstein Competition. I got second prize but I was criticised from all fronts for not having enough freedom of expression, trying too hard to be perfect, and in the last two years since then I've been trying really hard to move away from this kind of playing, and the Queen Elisabeth Competition was like a personal best for me. I think another thing with the Rubinstein is that I had to stop taking lessons from my teacher. He was on the jury and the rules said that one year before, so that's May 2010, we had to stop. At first it was hard and painful. But then, looking back now, I think that it was a good thing, that no-one else should tell you what's wrong and what's right, that you need to be responsible for every single interpretative decision that you take.

So you didn't seek out another teacher at that time.

No, and right now I'm on my own. It is hard, because you always think you make wrong decisions, and if you fall you get hammered, but I think that in the end it's very liberating. Because if I say not giving account to anybody it sounds haughty, but you become your own harshest critic. And then no matter what anyone said, if it was bad you know inside, and you know that you must work harder in order to get to where you know it would be good. Being on your own makes you listen more to yourself. So those things, plus the concerts I received from the Rubinstein and others, for me the concerts are the biggest driver forward. You practise and perform at home, but then you must go on stage and perform it for a real audience, and then everything comes sharply into focus, it's like a bright spotlight, and many things which were not clear become clear in the performance, and everything that is not good comes out. So in some ways concerts are the biggest lessons.

It's interesting you put yourselves through competitions when you were already quite well established – some pianists would argue that there's no need to do that. What were your reasons?

Several, for the Queen Elisabeth I have a soft spot because several of my biggest heroes have won it, for example Oistakh, Gilels, Ashkenazy, it has a special tradition going back to the 1930s. The image of it I had in my mind when I was there that it's a musical competiton, it's not about the usual things which some other competitions might or might not be about. The repertoire was very interesting, not standard repertoire, especially this imposed piece which you have in the finale.

You chose Prokofiev's Second as the concerto for the finale?

No, actually, that I played around the competion. The Prokofiev Second Piano Concerto we had a huge tour of afterwards. It was completely new to me – I played it for the first time in April, so just before the competition. I had the programme in January – then I hadn't played a single note of it, so I thought, this will be very, very challenging.

It's a piece that very few pianists used to be able to play, but now there are quite a few who do...

Oh, and this is for me an incredible work not in terms of virtuoso show but the colours, the way it goes like the Eighth Sonata, it connects directly with my visual imagination, there's such a very strong storytelling element.

He writes narrante, doesn't he, at the beginning and in the middle of the finale? And I wonder, what is it you're narrating, it's left to the pianist to decide.

Absolutely. And my personal belief is that sometimes it's better not to put it in words, because words have hard boundaries. There's this wonderful story by Ray Bradbury about a boy meeting an alien. And the alien doesn't want to be looked at, doesn't want to be named, because it's amorphous, the moment it is looked at or named it is forced into some kind of form. If you just have a vague idea in your subconscious or your guts, it works much better than if you try to go by the bar and give a definite story. Same with the Liszt sonata, almost everyone feels there is some story element...

A Faust drama...

But the moment you suggest Faust or whatever, I think it loses – OK, say Faust, but if you say this is Gretchen or this is Mephistopheles, it's less. The music is so direct, it bypasses some areas of the brain and goes to other places, and this power, we need to do everything we can to augment it and project it to the audience. The Prokofiev is like that. Well, Pictures at an Exhibition obviously...

...is tied by the descriptions of the pieces.

Yes, exactly – but even there, if you look at the original watercolours and drawings by Hartmann on which Musorgsky based his score they're nice, of course, but they're very different.

Looking back I say it was one of the most extraordinary times of my life, the intensity, being so focused, of wasting not a single moment

The Baba-Yaga original is just a clock, but he does the whole flight of the witch.

I mean, Musorgsky was one of those highly imaginative artists – if you listen to the Songs and Dances of Death, and if you see Vishnevskaya's performance, the way she acts, it's on YouTube with Rostropovich accompanying her, it's incredible, the way she looks at the camera, it's searing. And Rostropovich at the piano. It's amazing. So going back to the Queen Elisabeth Competition, I played Rachmaninov Third Concerto in the finals, but they also wanted a classical sonata of your choice, and that's the oldest tradition of the competition, a new concerto especially written for the occasion, which one learns in one week of seclusion, so we are driven away to a large house outside Brussels...

How many competitors?

Twelve in the finals, each one of us had a studio with his or her own piano, and we met for meals, and then the moment you arrive there you first of all are deposed of all your means of communications, no internet, no phones, and then you get the score. And we looked through it, it's 11 pages.

Who was it by?

A French composer of Armenian origin whose name is Michel Petrossian, the piece is called In the Wake of Ea, Ea is the ancient Babylonian god or goddess of subterranean waters and also the protector of music. If you're interested, it's also on YouTube. It's really difficult but a very interesting and rich work.

Because the danger is you're faced with something that you have no connection with at all.

Well, this was our first impression. It's tonal, it's not regular harmony, but it has a very well-defined harmonic vocabulary, and it's got plenty of explanations behind it, as often they have no connection with the music at all, but on day five or six I started feeling that the music wanted to go somewhere, like in real music, in Beethoven or Schumannn where the music leads you forward.

Did you have a second pianist playing the orchestral part in run-throughs?

We had a full score, a karaoke recording with orchestra, but we all worked in small groups, it would have been impossible otherwise, there was one night when we worked until four in the morning to learn the orchestral score. Everyone worked alone on their programme for 12 hours a day, but no-one would have made it through on their own, and we all got support from one another psychologically, because it was a very tough week. Looking back I say it was one of the most extraordinary times of my life, the intensity, being so focused, of wasting not a single moment, I never achieved this level of concentration outside...

And the isolation is very special.

There it was tough, because there was this total lack of security, of knowing what was going to happen. We were there seven whole days plus day of arrival and day of performance. The concerto was 16 minutes long, a proper piece and a very large piano part, and at the same time we had to prepare the main concerto and the sonata, rehearse with the orchestra.

And what was your sonata? Beethoven Op. 90. Because the concert itself had to be within certain time limits – because Rachmaninov Third Concerto is very long I had to limit it. But I can't tell you how happy I am that I was able to end my competition career on this note with this competition and this prize.

Beethoven Op. 90. Because the concert itself had to be within certain time limits – because Rachmaninov Third Concerto is very long I had to limit it. But I can't tell you how happy I am that I was able to end my competition career on this note with this competition and this prize.

The perspective from my view was that you'd already arrived.

Well, it's definitely been hard work since then. This season is overflowing with more than 80 concerts, with engagements in areas of the world where I haven't played before...

This programme that you chose was very deep. I do remember Peter Donohoe trying to play the Rachmaninov Preludes in that same hall, also on a Fazioli piano, and fatally one of the pedals squeaked, it kept stopping and starting, so we didn't get the full sequence straight through and I don't think he connected them in the way that you did, but this wonderful sequence, everything complements everything else.

Exactly. It's amazing how every prelude works on its own, if you want to pluck it out of the cycle, but in context there are really well thought-out harmonic connections, and just playing, you have the absolutely certainty where to start the next one. It's not a conscious choice, you lift your hands and it's like taking a breath before saying the next sentence, and you're there. It's a big pleasure to play. I was looking in the last few weeks at Op. 32, and it's very different – much more muscular and I suppose you could say manly.

It's the 13th that is just so big and amazing, so simple but so strong.

I found up to now six of them that I really loved, out of the 13, a few that I didn't get from the first feeling, but in the first set there's a kind of exuberance, of sheer delight in the music.

And flight at the end of No. 8.

So special, yes, flight – I know you can approach it differently. I know for example that I play No. 9 significantly slower than Rachmaninov wrote – he says presto and the metronome is almost twice as fast, but it's such a beautiful melody and there are harmonic changes on every demi-semi-quaver, and if you just whizz through it that just disappears.

That was the other thing, the melodic line never got swamped by surrounding notes, and when the textures were rich they informed it. The melody is so important, so unusual...

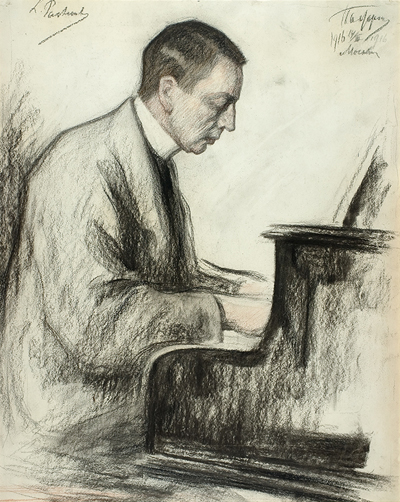

Well, that's Rachmaninov (pictured right by Leonid Pasternak in 1916), it's one of his best gifts. I'm in love with it.

Well, that's Rachmaninov (pictured right by Leonid Pasternak in 1916), it's one of his best gifts. I'm in love with it.

Would you do the Op. 39 Etudes-Tableaux as a set? I think they're his greatest solo-piano music played together.

Yes. I played seven of them already so I've missed two, and I will.

Again, there's no doubt where the centre of gravity is, in No. 7 with the funeral march and the bells.

I played it at a competition, and also the way you get those images when the climax starts building. I remember as a kid, I wanted to play this when I was 14, i was just hooked when I heard it.

Interesting, because it strikes me as quite a mature, philosophical piece.

Well, of course when you're that age you just get the coolness of this and the climaxes. But it's amazing how Rachmaninov goes right here into your heart, guts, belly, whatever.

The other thing I really loved last night, it's often said that the sign of a great interpreter is not so much how you begin but how you round off – and he, in every single ending of those Preludes is so unexpected – there's something thrown in just before the end. Also the trouble with the Wigmore Steinway is that players often mash that final chord, it's that twangy sound, and you never did that once.

The Fazioli yesterday, I was really happy with it – Yamaha is my home piano, the one I've practised on since '94, it's a baby grand and it works for me for 12 hours a day, no problem. And it has got a silent piano system so if I need to practise at night that's helpful. But I must admit as much as I could be I'm brand-agnostic. I played just two months ago on an extraordinary small Bösendorfer. Even though I'm not a Bösendorfer fan, this one was really superb. I've played some very good Yamahas, of course the Steinway is my home sound, my beloved sound, but the Steinway of 30 years old, that slightly old-fashioned, very rounded bell-like tone, this is something that I felt yesterday, on this particular Fazioli which I've played a few times before. The Fazioli has a fantastic action, but when it's coupled with a sound like that...

Did you find it was particularly useful for those distant, bell-like sounds, for example that passage in the first movement of the Prokofiev (pictured below: the composer as a young man) where time stops and there are just chimes in space... like music from another planet?

Oh yes, actually this was something I discovered during the concert. This was not planned, this is one of the joys of live performance. You know, we always have to adjust to each piano every single time. And some of it is a negative thing, because you never get to know one piano really well. Except for your home instrument you don't have this knowledge. And then if the piano is really good it can suggest things to you that you wouldn't have thought about, and there is this give-and-take which is one of the big joys of playing live. This really was one of those things, I played that phrase, I thought, Oh, this is a nice funeral thing, and then what came next was a direct reaction to the sound that I had from the bottom chord, so if the chord would have been different, the connection would have been different.

Oh yes, actually this was something I discovered during the concert. This was not planned, this is one of the joys of live performance. You know, we always have to adjust to each piano every single time. And some of it is a negative thing, because you never get to know one piano really well. Except for your home instrument you don't have this knowledge. And then if the piano is really good it can suggest things to you that you wouldn't have thought about, and there is this give-and-take which is one of the big joys of playing live. This really was one of those things, I played that phrase, I thought, Oh, this is a nice funeral thing, and then what came next was a direct reaction to the sound that I had from the bottom chord, so if the chord would have been different, the connection would have been different.

There were such moments of space.

This is something which I began to feel a year or so ago, this idea of a sound-space. There are several aspects: one aspect is that I would say the silence of an audience is very different from the silence of an empty hall, because it's alive. Then it's a little bit like if this silence were the sound-stage on to which we place the notes. It's like something which unites audience and performer. So much we're in our own world projecting it to the audience, but it's like the audience gave us the space onto which we place it. The other aspect is purely the piano. This is something which – less than a week ago I played at the [Leipzig] Gewandhaus. I basically had a choice of a new or old Steinway – the old one was one of these 30-year-olds I love, so no question. But one thing which really struck me was how different the sound-space each piano created on its own. I felt that older one was breathing, I felt like the bass was giving a space onto which I could immediately put the melody, whereas with the new Steinway, I felt it was so different – you felt every note by its own spot, but there was no unified space. So you could make a wonderful voice separation, the voices didn't mingle, so for polyphony it was extraordinary, much easier than the old Steinway. But starting this D major Prelude, on the old Steinway you had the sense of just a vast horizon opening. I think even Prokofiev in the Eighth Sonata explores this feeling of space consciously – he has constantly those three levels, the bass, the melody and a very active middle voice, and he especially separates them.

That struck me – the inner part writing is so chromatic. In the second movement he's taking quite a simple old idea, a minuet from his incidental music for Eugene Onegin, and what he fills it in with gives the poignancy – it's so desperately sad and nostalgic.

Yep. It's interesting how each one of us perceives the music differently. We as artists, it may sound funny, we have no influence on how the music is perceived by the audience. It's like a chain. The composer had a work in his or her head, that's already version a, then he or she put it to the best of his or her abilities, that's version b, it's like Wagner said when he heard Siegfried or was it Walküre, that it came short of what he'd imagined, which means there was another secret Walküre in his head which he did not achieve on paper. Then if he's not the performer, the performer gets the score, reads it, what's in their head is version c. Then they put it to the best of their abilities into music, that's version d. And what the audience hears is version e. Where is the work? I have no answer.

It's all of those, in a way.

Yes, it contains everything within itself.

And there are probably things in it that the composer might not have consciously thought of.

You know, some recordings by composers are extraordinary, think of Rachmaninov playing his work, but sometimes you get the feeling that he didn't quite understand what the composer meant...

Or they rush it. I think the frequent problem with composers is that they're almost afraid of what they've written.

Because of this in some ways the score is a bigger authority than a recording of the composer playing. Because I feel that everything is in the score.

And then you have to bring to it what you feel about it – that's why Shostakovich gave the interpreter total freedom, said don't bother about the metronome marking. So long as the attempt is sincerely made.

Some composers do have inbuilt larger freedom, like the margins are wider for what's acceptable, it still sounds right. In Mahler's Ninth Symphony, for example, you have recordings in which you feel that the darkness shines over the light, and others in which the light triumphs, and both feel valid in their own way. So this is like two opposites, both in the same work. And then you hear some Mozart performance, and right at the start you feel, it's not quite Mozart any more. I agree with you, anything that comes from a sincere place, from really trying to bring the score to life rather than force your own views on it brings interesting results, results which captivate the audience. I feel we're very lucky to be working with material of this calibre, we have this vast repertoire full of precious stones. (Image below by Sasha Gusov.)

So to go back to the original question, how has your attitude to that great Prokofiev sonata changed since you first recorded it back in 2005?

My feeling is that at that time I was not aware of my own playing. Things happened, if they would grow, I would not know how to do it again, if they went wrong, I did not really know how to correct – I wasn't always sure what was wrong, I could feel something was not good, but what? I don't think I'm quite there yet – some people have it, you go to a rehearsal with a conductor and there are some who know exactly what needs fixing. I imagine for a conductor it's different, because they must know. For us, we can allow some freedom of experimentation to find things out, because it's hands-on for us, while conductors must have such clear vision in order for other people to bring it to life. I did make some progress on that path of being self-aware, of being closer to express how I love the music. I haven't listened to the EMI recording for a very long time, I don't know how it was.

But already it seemed fully mature, it was the best interpretation I'd heard since Richter.

Richter, yes. It's a great piece. Sometimes you just wonder how someone sits with a blank piece of paper and writes this. How is it? I can understand how some of Bach's works were composed, I can see the inner workings. But the moment you get to the 19th century and then the 20th, it become a total mystery how people can get to this. Is it something they inherit in their minds and then just throw down? I don't know.

So a sense of the numinous – one got that particularly with the Rachmaninov, that it's half in this world but half somewhere else.

I'm so much in love with him, and you were asking about the Op. 39 Etudes-Tableaux, what a difference between the Op. 23 set and those. They're incredible. Also some of the lesser-known one, like No. 8 which follows after the C minor (sings it). You can play it as a self-contained piece, but it is a bridge between No. 7 and the last one. But there is something in the colour there that I haven't found anywhere else. What it makes me think of is one of those oriental, Chinese or Japanese scenes of autumn, a sense of deep melancholy. This is just my feeling.

Also the reward that you can bring out different voices, different colours simultaneously.

Especially in Rachmaninov, because his writing is so polyphonic, everywhere. Even if you just have the accompaniment and the melody, his left hands are incredible. They're like arabesques going alongside.

On which note, slightly changing the subject, I was astounded by the arabesques around the main lines in the Ravel (La Valse), and I couldn't believe that was his own version.

Well, some of the things are mine. The version itself is there.

There was a whole-tone passage there, was that you?

Yes, whole-tone then the second is octatone. There is a third line, and in the score preface it says the third line is there just to give context, because it's impossible or impractical to play, but everyone incorporates it somewhere. Some of those are chromatic lines which you just have to divide between hands, and some are glissandi, they just don't work with the harmony (sings a passage) – the glissando is on a seventh E flat major chord, if you play the glissandi on the black or white notes it doesn't sound right, so I just played a scale in that harmony. Then in the whole-tone passage, I just made it fit the harmony. The octatone scale I felt quite proud of...

Ravel loved his Rimsky-Korsakov, who invented it...

I don't think I ever in my life played an octatone scale anywhere else, because the fingering was so awkward to find for it. Then of course it comes back in the big climax. There I did it with two hands and lots of show.

The original, did Ravel write it before the orchestral version or after?

I think the order was two pianos, orchestral, one piano. But they all came around the same period. I love the one piano version more. You have the freedom. With two you're bound. It has to be more constant with the other player. Here there is some danger that if you play too freely then it loses the propulsion and becomes nothing. This is something I thought the Fazioli was incredible for, the colours in the Ravel.

If you look at the original songs, the accompaniment is sometimes very basic. Then you listen to Ella Fitzgerald with Nelson Riddle's orchestra and they become extraordinary

You were so relaxed in the Gershwin, it was as much of a pleasure as anything else, it wasn't just some funny little throwaway piece.

This is my arrangement. Here's the curious story. It's his song, he recorded a piano roll version, and on top of his own version he added two hands more, so it's for four hands. There's a transcription of that, and I did the arrangement for two hands. It's more difficult than some of the other stuff in the concert.

Would you do a Gershwin songbook?

Well, I've played the three preludes and the concerto, from the songbook I did "I Got Rhythm", but I don't know about the rest. If you look at the original songs, the accompaniment is sometimes very basic. Then you listen to Ella Fitzgerald with Nelson Riddle's orchestra, for instance, and they become extraordinary. So this is something I cannot do. Gershwin himself made arrangements of his own songs, but the only one which is elaborate is "I Got Rhythm". The others are just two pages, there's not enough there.

Just to wrap up on a broader note, I gather you've got a serious interest in photography and that you've also been doing some important translation work. What are you translating at the moment?

I've been working for almost two years now on a cycle by Rainer Maria Rilke, The Book of Hours, translating it into Hebrew, because English, Russian, everything else has been translated from already.

So you speak fluent German as well. How many languages altogether?

Six. French, German, Spanish, Russian, Hebrew and English. From English I've translated some of Shakespeare's sonnets. I did also some Robert Burns.

This is for your own pleasure, or were you commissioned by a publisher?

At the moment, it's just for myself. From Russian I also translated into Hebrew Pasternak, Akhmatova, a bit of Pushkin, Mandelstam.

So mostly poetry?

Only poetry. I started translating Winnie the Pooh when I was 17 because there was just an old and not very good translation, but when I was halfway through it, a new edition came out. Photography – it began two years and two months ago, when I lost my old camera and in looking for a new one it just took off. I'll give you a link to my blog. I've got one blog about my photography and one on classical music where I'm writing listening guides for non-musicians, so I take details and try not to water it down, but really show the essence.

Photography (one of Giltburg's copyright images pictured above) is a complete change of direction. It began as a hobby and now I'm getting really passionate about it. As for photography, I started reading, I've got a very good friend who is a serious photographer who's helping me, she's a good harsh critic and I benefit from it. The technical side I'm confident about now, what she helps me most with is quality control, what not to show, what not to put on the blog, which at the moment is something I still don't have.

You go to a lot of photographic exhibitions?

Yes, this year I've seen two great exhibitions, Ansel Adams in Greenwich and Sebastião Salgado at the Natural History Museum. I've got books of Adams, but seeing those prints is something else. The thing is, I go to the museum, I go to the photography room, I get more out of it, I don't know why, I connect ten times more than with paintings. Maybe because of the fact that I'm taking photos myself. It's also much more fascinating for me the way it's recreative, the way you take something that's already there, it's not from scratch. But then the way that your personal vision transforms it, there are endless varieties in the possibilty of the way you take one subject and show it in a million possible ways and giving a million different possibilities, I find it really fascinating.

- Follow Boris Giltburg's blogs: one of images, A Photo a Day, and the other including his listening guides, Classical music for all

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Add comment