Reissue CDs Weekly: Betty Davis, Jeanette Jones | reviews, news & interviews

Reissue CDs Weekly: Betty Davis, Jeanette Jones

Reissue CDs Weekly: Betty Davis, Jeanette Jones

Intriguing Sixties soul from the woman who married Miles Davis and a lost San Francisco belter

Despite their different paths in the Seventies, the final years of the Sixties saw parallels between Betty Davis and Jeanette Jones. Both soul singers had significant backing from music business insiders. Late in the decade, each had a discography limited to one unsuccessful single. They worked as models.

Davis is acclaimed for the trio of albums she released over 1973 to 1975 which captured a self-penned, sexually up-front feminist funk that was hard for a male-dominated industry to market. A fourth album was recorded in 1976 but shelved and first issued in 2009. The North Carolina-born Davis acquired her second name on marrying Miles Davis in 1968 – before then, she was Betty Mabry and had made a couple of small-label singles. In 1967, while living in New York, she wrote "Uptown (to Harlem)" which was recorded by The Chambers Brothers. Jimi Hendrix was amongst her friends. Major label interest came in 1968 and resulted in one single.

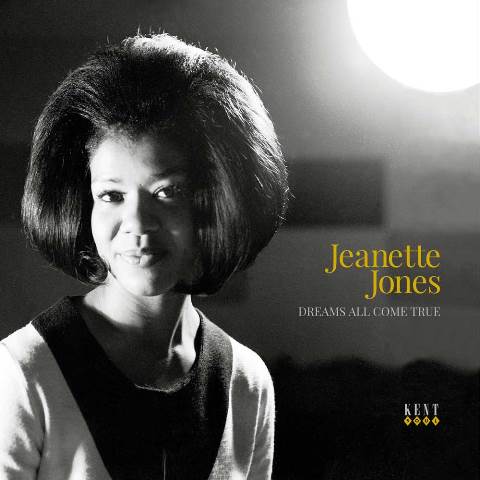

Jones (pictured right, courtesy Ace Records) wasn’t embedded in quite such a hip scene. A singer in San Francisco’s Voices of Victory choir, she didn’t embrace secular music until 1968. She had, though, already been spotted by Leo de Gar Kulka of the city’s Golden State Recorders studio and label. When she decided to try solo work, he leapt at the chance to record her and the result was the 1969 “Darling, I’m Standing by You”/ “The Thought of You” single on his own Golden Soul imprint. Despite regular recording sessions and hard work undertaken to get her onto a major label, she did not click and is last known to have recorded in 1974. Her current-day whereabouts are unknown.

Jones (pictured right, courtesy Ace Records) wasn’t embedded in quite such a hip scene. A singer in San Francisco’s Voices of Victory choir, she didn’t embrace secular music until 1968. She had, though, already been spotted by Leo de Gar Kulka of the city’s Golden State Recorders studio and label. When she decided to try solo work, he leapt at the chance to record her and the result was the 1969 “Darling, I’m Standing by You”/ “The Thought of You” single on his own Golden Soul imprint. Despite regular recording sessions and hard work undertaken to get her onto a major label, she did not click and is last known to have recorded in 1974. Her current-day whereabouts are unknown.

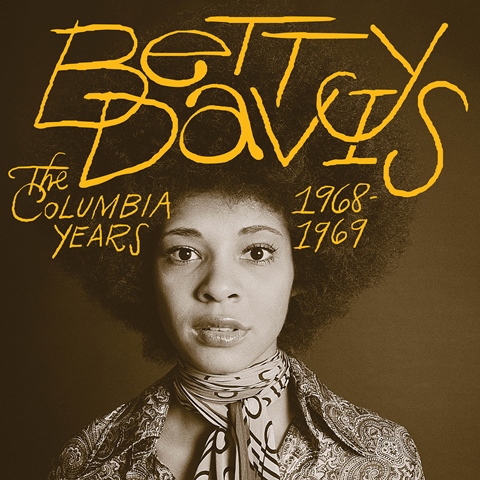

Two new releases raise the question of whether the recordings made by Davis and Jones in 1968 and 1969 could have brought them widespread recognition. The Columbia Years 1968-1969 collects nine tracks recorded by Davis from then: "Live, Love, Learn" was the B-side of her 1968 single, but the remainder are previously unissued (the version of "It's My Life" compiled is an alternate take of the single's A-side). The 12-track, white-vinyl album Dreams All Come True is the first-ever release collecting everything Jones recorded from the sole single to finished masters which weren’t issued.

The Columbia Years 1968-1969 instantly attracts attention due to its credits. Three tracks are from the October 1968 session which resulted in the single. The producer is Mabry’s then partner Hugh Masekela and players include guitarist Roy Gaines (a session man and Ray Charles’ sideman), Masekela’s pianist Cecil Barnard, violinist Tibor Zelig (Frank Zappa) and pianist Joe Sample. The rest were recorded in New York in May 1969 and produced by Miles Davis. The extraordinary line-up features Harvey Brooks, Bill Cox, Herbie Hancock, John McLaughlin, Mitch Mitchell, Wayne Shorter and Larry Young (Miles Davis does not play, and neither does Hendrix: scotching stories he had recorded with Betty Davis)

The Columbia Years 1968-1969 instantly attracts attention due to its credits. Three tracks are from the October 1968 session which resulted in the single. The producer is Mabry’s then partner Hugh Masekela and players include guitarist Roy Gaines (a session man and Ray Charles’ sideman), Masekela’s pianist Cecil Barnard, violinist Tibor Zelig (Frank Zappa) and pianist Joe Sample. The rest were recorded in New York in May 1969 and produced by Miles Davis. The extraordinary line-up features Harvey Brooks, Bill Cox, Herbie Hancock, John McLaughlin, Mitch Mitchell, Wayne Shorter and Larry Young (Miles Davis does not play, and neither does Hendrix: scotching stories he had recorded with Betty Davis)

Obviously, its cast list ensures that The Columbia Years 1968-1969 is a significant release. But it is Betty Mabry/Davis whose name would have been in lights if "It's My Life" had been a hit, and if the Miles Davis-produced tracks had progressed beyond the demo stage. “It’s my Life” and “My Soul is Tired”, two of the Masekela-produced tracks, are busy, percussion driven and despite a lack of vocal power have a mainstream edge akin to Tina Turner’s upbeat material – it’s easy to imagine the then Betty Mabry performing them on the Ed Sullivan Show. The third track with Masekela is “Live, Love, Learn”, an unmemorable ballad ill-served by its glutinous arrangement. The shadow of Tina Turner crops up again on the Miles Davis session with a sharp-edged take of CCR’s “Born on the Bayou”. A swampy run-through of Cream’s “Politician” implies ears cocked towards Doctor John. Of her own compositions, “Down Home Girl” and the second of two versions of “I’m Ready, Willing & Able” share the same southern quality but with an added groove hinting at what was coming in the Seventies.

Jeanette Jones was more about her voice than the overall feel. She was a belter. This was as just well as some of the anachronistic songs composed for her by manager Jay Barrett suggest he liked “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” and “Swinging on a Star” a tad too much. However – and it’s a big however – de Gar Kulka framed her in a way which transcends the schlockiness of a few of Dreams All Come True’s songs. This reservation aside, liberated from being heard in passing on a compilation, Jones is revealed to be a singer of great character and abandon.

Jeanette Jones was more about her voice than the overall feel. She was a belter. This was as just well as some of the anachronistic songs composed for her by manager Jay Barrett suggest he liked “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” and “Swinging on a Star” a tad too much. However – and it’s a big however – de Gar Kulka framed her in a way which transcends the schlockiness of a few of Dreams All Come True’s songs. This reservation aside, liberated from being heard in passing on a compilation, Jones is revealed to be a singer of great character and abandon.

The case is made with “Darling, I’m Standing by You” and “Cut Loose”. The former, recorded in March 1969, is plaintive, southern-style gospel-soul which suggests Jones as an Aretha Franklin in the making. “Cut Loose”, tracked in October 1968 over a backing recorded in LA, is extraordinary. Jones swoops and whoops as if she’s decided to be Eddie Floyd. Her voice was big, expressive and instantly impactful.

But Jeanette Jones did not find quite the right setting for the voice she was gifted with. It would have taken a label like Atlantic, Stax or a southern independent to give her exactly what she needed. Dreams All Come True shows her as a diamond in the rough. Committed soul fans will need the album. With Davis’ The Columbia Years 1968-1969, most of what’s heard are not finished masters for shopping to prospective labels – at this stage, Betty Davis was still a musical work in progress. And like Jones, the arrangements were not quite right for her voice. She needed the less busy bedding she found in the Seventies. But again, anyone with a passing interest in her will need The Columbia Years 1968-1969, as will Miles Davis completists.

As to the question, neither release suggests that Betty Davis and Jeanette Jones could have achieved widespread recognition in the Sixties. With Davis, that’s not a problem as she went to make a string of albums in the Seventies. For Jones though, it’s sad she never achieved her potential.

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Pop Will Eat Itself, O2 Institute, Birmingham review - Poppies are back on patrol

PWEI hit home turf and blow the place up

Pop Will Eat Itself, O2 Institute, Birmingham review - Poppies are back on patrol

PWEI hit home turf and blow the place up

'Fevereaten' sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

'Fevereaten' sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Add comment