How well do you know your bad Victorian poetry? “When through the purple corridors the screaming scarlet Ibis flew/In terror, and a horrid dew dripped from the moaning Mandragores.” Go on, guess the author. Or how about this? “What time the poet hath hymned/The writhing maid, lithe-limbed,/Quivering on amaranthine asphodel". Got it yet? The first is Oscar Wilde’s The Sphinx, from 1881. The second, WS Gilbert’s libretto for Patience – written in the same year, and skewering Wilde with gleeful relish and lethal precision.

If Liam Steel’s new production of Patience for English Touring Opera proves anything, it’s that the sheer accuracy of Gilbert’s satire is both a strength and a potential liability. Sullivan’s music makes Colonel Calverley’s Act One patter song bustle along so entertainingly (and in Andrew Slater’s performance it’s accompanied by vigorous physical activity) that that there isn’t much time to wonder about the exact cultural references behind Gilbert’s “Smack of Lord Waterford”, “Coolness of Paget” or “Swagger of Roderick”, to say nothing of the “keen penetration of Paddington Pollaky”. ETO provides a glossary in the programme, bringing to mind David Mitchell’s line as Shakespeare in Upstart Crow: ”It just requires lengthy explanations and copious footnotes. If you do your research, my stuff is actually really funny.”

But ETO’s Patience really is funny, and never more so than when Bradley Travis’s Reginald Bunthorne (pictured above) holds the stage. He languishes. He droops. He carries a huge peacock-feather quill and wears a floppy velvet cap. He strikes stained-glass attitudes on pedestals, he brandishes lilies and gazes soulfully from beneath his lank Early English haircut. Travis is the Bunthorne of your dreams; infinitely more than just an Oscar Wilde tribute act, he’s so far inside Gilbert’s ludicrous but basically loveable creation that you can imagine him going home and contemplating his blue china. His light, agreeable baritone is perfect for the job too, making him an ideal centre for the rest of this excellent ensemble cast. It’s a nice piece of vocal casting that Ross Ramgobin (pictured below, with Lauren Zolezzi as Patience) – dapper and droll as the more grounded, if equally vain Archibald Grosvenor – has a slightly richer, more sensuous voice; just as the slight signs of wear and tear on Andrew Slater’s baritone as Colonel Calverley befit an old soldier.

In fact, this whole production is proof of the old truth that the more seriously you take Gilbert and Sullivan, the richer the comic rewards: you could feel the audience’s sympathy swinging behind Valerie Reed’s Lady Jane (that’ll happen when the director sends you on to sing your big Act Two aria carrying a double bass). Lauren Zolezzi plays Patience wide-eyed and utterly deadpan: all the funnier when Travis and Ramgobin swoon and fawn over her, or when in her dainty milkmaid’s frock she effortlessly lifts a massive milkchurn. And all the more affecting – and delicious – when her clear, firm soprano peals over Sullivan’s high notes and curls elegantly round the end of a phrase. Steel keeps the action smartly choreographed, with cast and chorus (lovesick maidens in pastel gowns like something out of Lord Leighton, Heavy Dragoons, pictured below, belting out their choruses with brilliant clarity) forming suitably picturesque tableaux on Florence de Maré’s William Morris-patterned arbour of a set, though there were moments when transitions between scenes might have been tighter. The maidens, too, could perhaps have used a slightly larger repertoire of languid gestures.

In fact, this whole production is proof of the old truth that the more seriously you take Gilbert and Sullivan, the richer the comic rewards: you could feel the audience’s sympathy swinging behind Valerie Reed’s Lady Jane (that’ll happen when the director sends you on to sing your big Act Two aria carrying a double bass). Lauren Zolezzi plays Patience wide-eyed and utterly deadpan: all the funnier when Travis and Ramgobin swoon and fawn over her, or when in her dainty milkmaid’s frock she effortlessly lifts a massive milkchurn. And all the more affecting – and delicious – when her clear, firm soprano peals over Sullivan’s high notes and curls elegantly round the end of a phrase. Steel keeps the action smartly choreographed, with cast and chorus (lovesick maidens in pastel gowns like something out of Lord Leighton, Heavy Dragoons, pictured below, belting out their choruses with brilliant clarity) forming suitably picturesque tableaux on Florence de Maré’s William Morris-patterned arbour of a set, though there were moments when transitions between scenes might have been tighter. The maidens, too, could perhaps have used a slightly larger repertoire of languid gestures.

But Sullivan has a way of disarming all reservations – and I’m not sure that even Iolanthe has more enchanting music. “The most beautiful score written for the English stage since Handel,” declares conductor Timothy Burke, and he conducts like he means it, too: bringing up the blackness of the basses in Bunthorne’s mock-tragic Act One confession, letting oboe counter-melodies soar weightlessly over vocal ensembles and making Sullivan’s exquisitely detailed accompaniments dance like gavottes. The orchestra responded with brightness and grace, reinforcing the sense that ETO has rediscovered a real treasure and presented it with affection and a winningly light touch. If Patience had a French name on the title page (and musically, it’s easily in the Chabrier class), it would be staged with huge fanfare (and budget to match) at Covent Garden. Let’s just be grateful that it doesn't.

Patience is touring with Blanche McIntyre’s new production of Puccini's Tosca (Act One pictured above), and some early reviews were unkind, with Florence de Maré’s semi-abstract set coming in for particular flak. You can see why: the backdrop is midnight black throughout and the same obstacle course of grey latticed walkways and steps serves for all three acts, helped and occasionally hindered by Mark Howland’s lighting (a spotlight on Tosca for Vissi d’arte – come on now, seriously?). Actually, there’s far worse out there. De Maré’s set is at least as effective as Frank Philipp Schlössman’s designs for ENO’s lacklustre recent Tosca, and rather more consistent as a concept. It’s just that – however nimbly the cast negotiate it, and however effective it proves for staging big moments such as the Te Deum at the end of Act One, or Tosca’s final (and in this production, genuinely hair-raising) death leap – the presence of a massive trip hazard centre stage prompts thoughts of risk assessments rather than love and art.

But with that proviso, what we saw at Wolverhampton Grand Theatre was a red-blooded Tosca with all the essentials very much in the right place, and in Paula Sides’s Floria Tosca (pictured above with Samuel Sakker) a performance of really compelling intensity. This is a woman who’s been wound up to breaking-point: Sides transforms in the flash of an eye from jealous spitfire to clingy young sweetheart, and her voice has a fierce, focused intensity that can snap, whip-like, from tremulous fragility to searchlight brilliance. She colours each word. Simultaneously girlishly impulsive and effortlessly sensuous, in her final scenes with Cavaradossi she was wide-eyed with euphoria: a woman who might perfectly credibly jump off a battlement. You wondered if Samuel Sakker's Cavaradossi knew exactly what he was dealing with – his wide-grained, dark-hued tenor wasn’t always matched by smooth phrasing, but his transition from the sunny young artist of Act One to brutalised, unbelieving victim in the final scenes was persuasive. ETO has double-cast the three principal roles, but Craig Smith (pictured above) appears as Scarpia in all but six performances. Tall, pale and harsh-featured (and really inhabiting de Maré’s greatcoated and jackbooted Napoleonic-era costume) he cuts a predatory figure: cruelty radiating from gimlet eyes. His vocal performance matches his appearance. Breathy, and occasionally breaking into a bark, it’s not the sonorous pitch-black singing we’ve come to expect from a Scarpia, but it never felt less than appropriate to this distinctly reptilian reading of the character. As is often the case with ETO, minor roles are cast from strength: Matthew Stiff’s bumbling, complacent Sacristan and Aled Hall’s uniformed pit-bull of a Spoletta were as characterfully acted as they were sung. Michael Rosewell conducted with headlong energy, finding colours – splashes of harp, snaking bassoon counterpoints – in the slightly reduced orchestration that can go unnoticed with plusher outfits (I don’t think I’ve ever heard the different bells of the Roman dawn sound quite so distinctive).

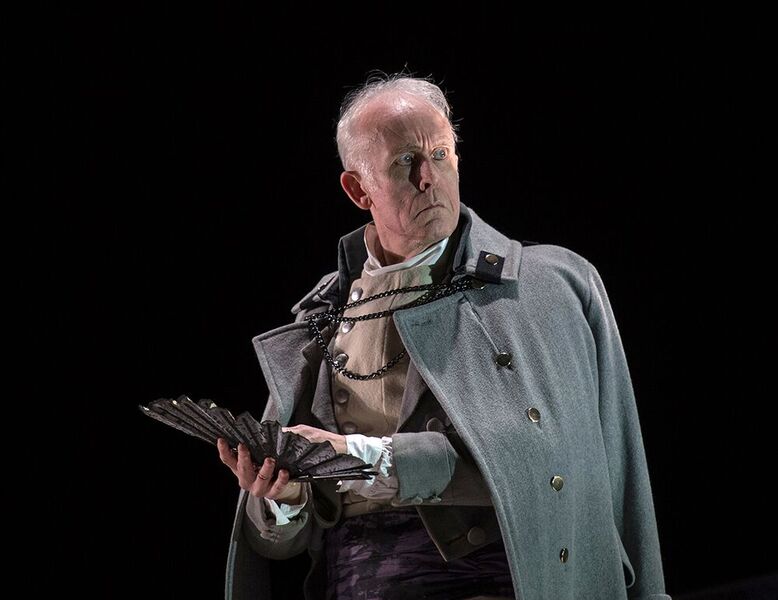

ETO has double-cast the three principal roles, but Craig Smith (pictured above) appears as Scarpia in all but six performances. Tall, pale and harsh-featured (and really inhabiting de Maré’s greatcoated and jackbooted Napoleonic-era costume) he cuts a predatory figure: cruelty radiating from gimlet eyes. His vocal performance matches his appearance. Breathy, and occasionally breaking into a bark, it’s not the sonorous pitch-black singing we’ve come to expect from a Scarpia, but it never felt less than appropriate to this distinctly reptilian reading of the character. As is often the case with ETO, minor roles are cast from strength: Matthew Stiff’s bumbling, complacent Sacristan and Aled Hall’s uniformed pit-bull of a Spoletta were as characterfully acted as they were sung. Michael Rosewell conducted with headlong energy, finding colours – splashes of harp, snaking bassoon counterpoints – in the slightly reduced orchestration that can go unnoticed with plusher outfits (I don’t think I’ve ever heard the different bells of the Roman dawn sound quite so distinctive).

Of course, with casts varying over ETO’s long tour, your experience may differ. And this isn’t a Tosca for WC2 canary fanciers. It’s Puccini in his natural element: built for big audiences and theatres of all sizes; fast, punchy, passionate and raw, and designed to grip a crowd like the incomparable thriller it is. It’s a tribute to McIntyre, Rosewell and their compulsively watchable cast that on this night, at least, it ended up doing quite a lot more than that.

Add comment