Jeremy Irons: 'I was never very beautiful' - interview | reviews, news & interviews

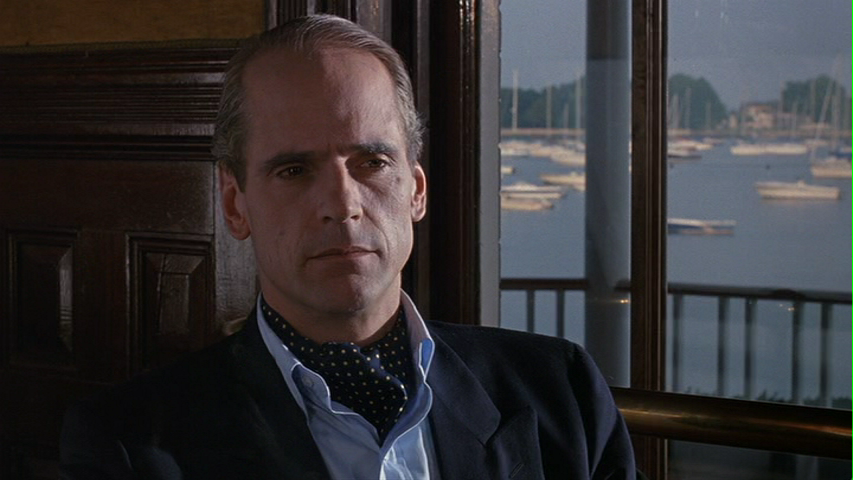

Jeremy Irons: 'I was never very beautiful' - interview

Jeremy Irons: 'I was never very beautiful' - interview

In his 70th year the actor looks back on Olivier and Gielgud, on the Oscars and his start at Bristol Old Vic

In 2016 the Bristol Old Vic turned 250. To blow out the candles, England’s oldest continually running theatre summoned home one of its most splendid alumni.

Eugene O’Neill’s monster play tells of a titanic family implosion in which an actor-manager who has saddled himself with the same part for years cracks up as his wife (played by Bristol by Lesley Manville) succumbs to alcohol addiction. Two years on, Richard Eyre’s production resurfaces at Wyndham’s Theatre in the West End.

This year Irons, who once had a long-lost stint as a children’s TV presenter, turns 70. Does he still feel gratitude for that big break in Brideshead? How was it to act opposite Olivier and Gielgud? Does he mind that a generation of children know him as the voice of an evil Disney lion? Could he have been Bond? Read on for the answers to these and many other questions.

JASPER REES: You returned for the 250th anniversary of the theatre to be in Long Day’s Journey into Night. It’s a mammoth role. What was the draw?

JEREMY IRONS: It’s great to celebrate this iconic play which I saw Olivier do. When I was asked to do it I thought if I do it’ll be a real workout but I need a workout. Richard Eyre asked. I’d quite recently done The Hollow Crown on television. I did Henry IV with Tom Hiddleston playing Hal, Richard was the director, it had been a very happy shoot and I liked him and admired him. And I’d seen his production of Ghosts at Trafalgar with Lesley which I thought was tremendous. (Pictured below: Jeremy Irons as Henry IV)

This is a Bristol Old Vic production. What are your memories of training there in 1969?

‘69, was it? Phwoof. Well, very fond. I was a student at the school and there for two years and we watched every production and on first nights a group of us would dress up in our black tie and go down and host the audience in, and for that we were able to watch for free the production. And then after the two years at the school I was one of the five offered a job there and although I can’t remember the first show I did, I spent three years. I started off as an acting ASM which is where you muck about backstage, moving the scenery and making the props. It was really good because what it taught you was the way a theatre works and who’s important. And if you missed that bit of the process you can have the mistaken illusion that it’s the actors who are important. Of course it’s not. The actors are part of a team. And if it isn’t lit right and the stage isn’t designed well, then your work suffers. And I’ve always got great joy now on a film set or in the theatre of that sort of teamwork where we’re all trying to do our best around a particular story, and I learnt that at Bristol. (Pictured below: Jeremy Irons and Lesley Manville in Long Day's Journey into Night at Bristol Old Vic, by Hugo Glendinning) I began to learn a bit about acting, not a lot. I loved my time there. Of course when I was there the backstage, everything behind the proscenium arch, was the same age as the auditorium. And it had been built by shipbuilders in 1766, and you could tell. It felt like a ship. All the ropes were like ropes for the sails. And of course immensely dusty. I remember changing one of the sets which we had to do through the night – I was a bit asthmatic at that age and I would get into bed at five in the morning wheezing away. But it taught the respect and the love of the old theatre. Then I remember Harold Wilson coming down on the last night and talked to all the cast as we retired from Bristol and went to Bath for three years or something while they knocked down that backstage. I remember we started a campaign to try to stop it happening and we couldn’t. It was the days when city planners – great theatre designers they thought they were – wanted to create a big backstage area so that shows from the Old Vic could be transferred to London. And they built what is quite honestly a sort of monstrosity. Such a shame because here was an integral period theatre. I remember seeing the wrecking ball going through the wall of my dressing room. I was standing behind the theatre as it swung in and the bricks cascaded down.

I began to learn a bit about acting, not a lot. I loved my time there. Of course when I was there the backstage, everything behind the proscenium arch, was the same age as the auditorium. And it had been built by shipbuilders in 1766, and you could tell. It felt like a ship. All the ropes were like ropes for the sails. And of course immensely dusty. I remember changing one of the sets which we had to do through the night – I was a bit asthmatic at that age and I would get into bed at five in the morning wheezing away. But it taught the respect and the love of the old theatre. Then I remember Harold Wilson coming down on the last night and talked to all the cast as we retired from Bristol and went to Bath for three years or something while they knocked down that backstage. I remember we started a campaign to try to stop it happening and we couldn’t. It was the days when city planners – great theatre designers they thought they were – wanted to create a big backstage area so that shows from the Old Vic could be transferred to London. And they built what is quite honestly a sort of monstrosity. Such a shame because here was an integral period theatre. I remember seeing the wrecking ball going through the wall of my dressing room. I was standing behind the theatre as it swung in and the bricks cascaded down.

Back to Olivier, you have talked about the sense of rivalry that he brought to your scenes when doing Brideshead Revisited. “He never felt that he’d got there and neither will I." Does that still obtain?

Oh absolutely. In fact I think it was in his first biography that he said you get to the top of a mountain and you think you’re there and you look and there’s another valley and higher mountain. Long Day's Journey is the high mountain.

How high is it?

It has an immense amount of verbiage. It’s very emotional and yet the character has long scenes where his wife is just going on and on and on in her hallucinatory state and you’re given no clue by the playwright about what you’re doing, what you’re feeling. So you have to design all of that. I find it fascinating because they all talk about each other in the play, they describe each other, and he has quite different colours from how he is perceived by the others. That’s true to form. O’Neill doesn’t judge any of the characters. And I know how people are truly different from how they are perceived. We perceive our father in a particular way but actually his lover would perceive him quite differently and he would be even different from those two perceptions. Also one of the problems with the play is that O’Neill was never produced in his lifetime and he actually never wanted it to be produced because it was so close to him. But anyway his second wife decided to produce it and because he was dead and because he was O’Neill you’re loath to play with it, whereas had it been produced in his life the director would have said, “Shall we cut that bit?” or “What do you mean by that?” We’re giving it a good zip but it’s hard for an old man. And the older you get the harder it is to retain lines. You say you need a workout. Why?

You say you need a workout. Why?

You can get a bit lazy, film acting. You don’t have to play a long phrase of three hours, you don’t have to communicate to an audience, you’re just communicating with a camera. Yes you have to think but you’re thinking in much shorter spans. You’re able to knit little bits together. That’s done, that colour, I can do that colour tomorrow, or whatever. It’s not easy work but I think it’s less of a … I would compare film acting almost to – it’s not a very good analogy – to playing chess. You’re trying to get the game right.

The analogy suggests you’re trying to beat someone.

No. That’s why it’s not a good analogy. Maybe making a patchwork quilt. You’re sewing really nicely round that bit of fabric. Whereas doing something like Long Day’s Journey is like doing a long-distance run without falling over and making it interesting for people to watch.

Do you get nervous?

I hope not. Not if I’m prepared. If I feel unprepared then I do. And what my task is during the rehearsal period is to be so prepared that I sling it and bring with me to the performance what’s happened to me that day, so it has a freshness. But you have to be really on top of it to do that. You can’t be thinking, what’s my next cue?

There must some parts of the profession that get easier.

It’s strange. I always feel like a plumber when I’m approaching a part. I never have a feeling of knowing how to do it. When you are in the process you are “Oh yes I found that easy” so there are things there. But I always feel like a beginner with a new character.

Are you getting better?

I couldn’t say. I don’t know. I really don’t know. I couldn’t judge. I think probably not. I know more, I’ve lived longer, so I have a little bit more to draw on. But my process is the same. A muddled process.

A plumber fixes stuff, often a blockage.

Blockages I know all about. I choose plumber because it’s just completely separate from acting.

A competent technician.

You’re reading too much into my plumber analogy. What I mean is someone who is a layman, a butcher or a newsagent.

This is one of the great plays about an actor. Does something chime with you?

Of course it does. I look to somebody like Kenneth Branagh who I admire enormously or Simon Russell Beale who I admire greatly too. I remember in my 40s talking about wanting to start my own company and I never have. Simon’s played quite a lot of stuff. And he was the young shepherd when I did Leontes in The Winter’s Tale. I’d just done The Mission. I look at those careers and I think, should I have spent more time in the classics? Should I have put back more into English theatre than I have? I could have possibly been an interesting Shakespearean actor and I haven’t done him for a long time and yet in truth I never really had the desire to. I always used to feel, so and so can play that part so much better than me. (Pictured: Jeremy Irons and Robert de Niro in The Mission) Who would that be?

Who would that be?

Depends on the part.

You must have been offered Lear.

I have been and quite honestly at the moment I don’t have the energy. I mean Lear is massive.

If you can do this you can do that.

We’ll see. I always wanted to do a Hamlet that was directed by Harold Pinter because I thought we’d find something quite interesting.

What did he say?

I don’t think I ever asked him. I might have mentioned it and he didn’t bite. I don’t know. I have been asked by a director who shall be nameless if I can be her Lear and I just said, “We’ll see. Not today anyway.” And I don’t actually know the play very well. I saw the most wonderful production at the National with Ian Holm which I thought was almost definitive.

Directed by Richard Eyre.

Was it? Oh, I haven’t talked to him about that. I’m not a person who lives with regrets. I’ve made my bed and I’m very happy and I sleep well in it at night. Things could have gone a different way. Would I have been happier or not? I don’t know. I look back at my life not with satisfaction because I’m never satisfied with what I do, but I’ve been very lucky. I’ve done a lot of disparate things, some of which have given me great joy at the time. And of course I don’t know what I’ll do. My appetite is not to work as hard as I wanted to when I was in my 30s and 40s.

How long can you not work for?

If I knew for instance that I had a job that I really wanted to do in a year’s time, very happy not working for a year. I think the thing that disturbs me a little bit is – not that it often happens, fortunately – having nothing coming up. I like to know my time is limited and then I’ll plan well within that time.

Earlier you said that others see us differently from the way we see ourselves. How do you think my profession has seen you? Have you recognised yourself in interviews? Sometimes. I’m very wary of your profession because they sometimes hang me out to dry. I’ve become fairly hard-skinned about that. I think sometimes journalists come with an agenda. They come with their story and hope that what you say will fit into that story and if it doesn’t quite… we know what writing can do. So I would say I am wary. I’m often my own worst enemy because I love flying kites and I’ve realised now you can’t do that. Wrong place.

Sometimes. I’m very wary of your profession because they sometimes hang me out to dry. I’ve become fairly hard-skinned about that. I think sometimes journalists come with an agenda. They come with their story and hope that what you say will fit into that story and if it doesn’t quite… we know what writing can do. So I would say I am wary. I’m often my own worst enemy because I love flying kites and I’ve realised now you can’t do that. Wrong place.

Does High-Rise (pictured above) feel it’s saying something about the state we’re in now?

You’ll get a better feeling of that seeing it fresh than I will. He makes it very Thatcherite and 1980s. I think he could have made it present-day. Does it have reverberations for today? I suppose. I think the film is better than the book but I didn’t much like the book, although I’m a great admirer of Ballard and turned down the opportunity to play in Crash, which I’ve always rather regretted. Not seriously because I don’t regret anything seriously. So I can’t really answer that question.

Would Tom Hiddleston make a good Bond?

I think he’d be a wonderful James Bond. He’s a fairly conventional James Bond but he has the style, the wit, the looks and the physique.

Would you have fancied it, once upon a time?

I once had a meeting about it. Who rejected whom?

Who rejected whom?

Neither of us rejected either really. It was a time when Roger Moore was saying he wasn’t going to do any more and I think he was probably doing it to up his fee. I was making The French Lieutenant’s Woman. Cubby Broccoli came down. We had a meeting in Lyme Regis and I wasn’t actually very interested because perhaps wrongly I thought it’s such an iconic role I would find it hard to get away from it. Doesn’t seem to have affected Sean [Connery] at all. I think it maybe has affected Pierce [Brosnan] a little. Don’t think it’ll affect Daniel [Craig]. I don’t know. I think it hangs round your neck a bit. (Pictured: Jeremy Irons and Meryl Streep in The French Lieutenant’s Woman)

Have there been roles that have hung round your neck?

Not uncomfortably so. I mean Brideshead has hung round my neck like a necklace. I’ve always loved it. I’m very proud that it has legs, that it’s still played on various channels and doesn’t seem to have aged. I think it’s good work on everybody’s part and it was certainly a wonderful experience doing it.

Is it true you get pissed off when they mention your contribution to The Lion King?

[Laughs] It’s not been a millstone round my neck at all. That’s the thing. Things you’re successful in, they’re there, they’re colour. If you’re hugely successful in them that’s a big colour.

What’s it like watching yourself getting older?

I was never very beautiful. I always had a bit of an odd face and I still have an odd face. It’s just different. I don’t really mind how I look. The only thing I mind about is how much the character is communicating to me through that body, through that face. It’s faintly curious to see me young. Have you ever seen Brideshead?

Have you ever seen Brideshead?

Since it went out? No.

You’ve tended to play quite well-to-do characters. The poshest person in Batman vs Superman, for example.

I know why. I sound like I sound. I’m tall and slim. A huge part of what we present is our physique and the way we sound and if somebody wanted me to play a five foot two Geordie who was 34 they wouldn’t come to me. That’s the nature of the business.

Do you regret you haven’t been cast as the odd oik and spiv?

I’d love to do that. Diversity is what I’ve always tried to get. But I’ve had what I’ve had. I try and muscle sideways from people’s perceptions but it’s not easy.

Olivier was rivalrous in his 70s. How do you feel you measure against him now you’re doing this role?

Oh, way down. Way down. I remember reading his biography and there’s a list at the end of chapter two or four of all the roles he plays and it takes up about a page and at the bottom it said he did this work by the time he was 27. It was six times the amount of work I’ve ever done.

But that was then.

I know but of course that develops a more rounded, a more talented actor than I could ever become. He was a different sort of actor than me. He was more of a showman I think than me. But he was for me iconic, as Gielgud and Ralph Richardson and Scofield were.

You had scenes with both of them in Brideshead. They weren’t close with each other.

No.

Could I ask you to compare acting with them?

I spent more time with John because he was around for longer. I remember going to dinners with him and I’d just read his autobiography and he would tell these wickedly funny stories at dinner and I would say, “Why isn’t that in your autobiography?” And he would say, “I couldn’t write that, dear. I couldn’t possibly. Upset too many people.” A shame of course because that’s what an autobiography should be full of. But Larry I remember was not well. We had this big death scene and he was sleeping in the next room in Castle Howard to the room we were filming in. I just had to kneel at the end of the bed and watch him make the sign of the cross before his death and knew that he’d come back to the Catholic church and this was an important part of the story. And Charles [Sturridge, the director] came to me and said, “‘Listen, I don’t want to get Larry up too early. Would you do your bit at the foot of the bed first?” And I said, “Charles, no. I have to react and feel to what he does. I can’t act and feel to something I imagine he’s going to do. You’ve got to get him.” So he did and Larry came in and got into bed and said, “Gather you can’t do it without me, dear boy.” I said, “You’re dead right, sir.” I just know that I feel like a child at the foot of a mountain compared with what I saw him do.

Was Gielgud more generous?

No, I have to say they were both very kind and considerate and well mannered and well behaved. Gielgud was struggling with continuity – he was eating fish, I remember – and the way they were shooting it he had to match from various angles and when you’re eating fish and you’ve got bones and all that, it was really hard, and speak. And I saw him struggling and I thought, God I’d be struggling too. I asked him about one line. I said, “Sir John, how would you say this?" Because I felt I wasn’t getting it right. And he [makes a noise of saying a line]. So I went outside while they were re-lighting and sat in the corridor going, doesn’t sound right at all to me. And of course you realise that what works for one actor doesn’t work for another. But he was lovely. You really have to do a theatre run with an actor to really get to know them. And then at that point they’d both had their fingers slightly burned by the Joe Orton generation when everything was new and acting was kitchen sink now. I think they felt perhaps their advice was not welcome, which I really regret, because I think acting should be passed on.

Do you make an effort to do it yourself?

When asked, but you’re not often asked. And you have to be very careful because people are very protective of their own work and what they’re doing and I’m not very politic. I normally go through the director and do it that way if there’s something I feel very strongly about. But when it’s somebody my age talking to somebody younger, they feel they’re being told. Their perception of that actor is he knows how to do it. Now, you don’t feel that way as an actor. You’re just exploring in the same way that a young person is exploring. You suggest. You say, “You could try that but you don’t have to, it might not work.” You have to really be careful, because they think you’re wise and you know how to do it, and course you’re not and you don’t. So it’s very difficult. Even as a director. I watch Richard Eyre and he’s wonderful the way he doesn’t impose. He’ll give a bit of a nudge in a certain direction but very very carefully. Howard Davies used to say about me that I’m a fundamentalist. He said, “You want it changed now, you want it different now. You’ve got to wait. Performances, plays – they ferment. Some people ferment quicker than others and you’ve got to let it happen and not get impatient.” Great lesson for me. Is there ever a sense of self-loathing at being someone who pretends to be other people for a living?

Is there ever a sense of self-loathing at being someone who pretends to be other people for a living?

No because I do believe… I don’t think actors, entertainers, deserve the amount of attention they get. It’s the way of the world. But people love to know about them. Less so now but nevertheless. But I think storytelling, which at base is what we do, is an important component of society. So that we can live our fears, live our fantasies through story, whether it be novels or film. And I’m a bit of that process. but I’ve always been aware that I don’t warrant the coverage that I get.

And if there were none, if the tap were turned off and the world stopped noticing, would you accept that happily?

I would. I’d probably not get employed. That’s the trouble. You know what they’re doing now? If there are two young men who are up for a role – two young women, whatever – and one has 1,000 Twitter followers and one has 100,000, the one with 100,000 will get the role. Nothing to do with…

And how does that make you feel?

I just think it’s madness. Absolute madness. But it’s life. And just as when I started out you didn’t have to sell a show, they didn’t have publicity, billboards, whatever. But even when we went up for Oscars for Reversal of Fortune the Oscars were on the Monday, I flew into New York from London, did Saturday Night Live, flew on to Los Angeles on the Sunday, did one party, and the following day were the Oscars. That was the only campaign. Now they campaign for months! I didn’t do a campaign. (Pictured above: Jeremy Irons as Claus von Bülow in Reversal of Fortune)

Did it change your life, winning that Oscar?

No. I mean it’s lovely. It didn’t harm it. It didn’t change my life as much as being the lead in a film that had huge box office would have changed my life.

And yet you didn’t pursue them when you could.

I was never really offered a great movie. We were going to do Remains of the Day but I don’t think that ever made a lot of money. I was going to play the Tony Hopkins part. Meryl was going to play the part Emma Thompson played and Harold was going to write it. And it all just fell apart.  It is sometimes said in some places that the Reversal of Fortune Oscar was an apology for not having won the Oscar before in Dead Ringers? (Pictured above: Irons in Dead Ringers)

It is sometimes said in some places that the Reversal of Fortune Oscar was an apology for not having won the Oscar before in Dead Ringers? (Pictured above: Irons in Dead Ringers)

I think that came about because I thanked David Cronenberg in my speech.

Do you think it’s an empty story?

No, I don’t because there was a – it even got to me so it must have been quite big because I was over here – a feeling in Los Angeles that it was very wrong that Dead Ringers was not nominated, and it got a lot of attention among the aficionados of the business. And so when Reversal came along the next year I think that groundswell encouraged my producers to say, “We’re going to do an Oscar campaign for you.” Which is a decision they make. You don’t just get nominated for Oscar. There is a campaign to get it. And had Dead Ringers not happened, I wonder whether they would have had that confidence.

- Long Day's Journey into Night at Wyndham's Theatre from 27 January to 7 April

- Read more interviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment