theartsdesk at the Lucerne Easter Festival: Haitink, Schiff and an alternative Passion | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk at the Lucerne Easter Festival: Haitink, Schiff and an alternative Passion

theartsdesk at the Lucerne Easter Festival: Haitink, Schiff and an alternative Passion

Greatest living conductor lights the way as mentor in three days of musical excellence

Anyone passionate about great conducting would jump at the chance to hear 89-year-old Bernard Haitink giving three days of masterclasses with eight young practitioners of the art, his eighth and possibly last series in Lucerne (though he's not ruling anything out). That was the hook to visit this year's Easter Festival.

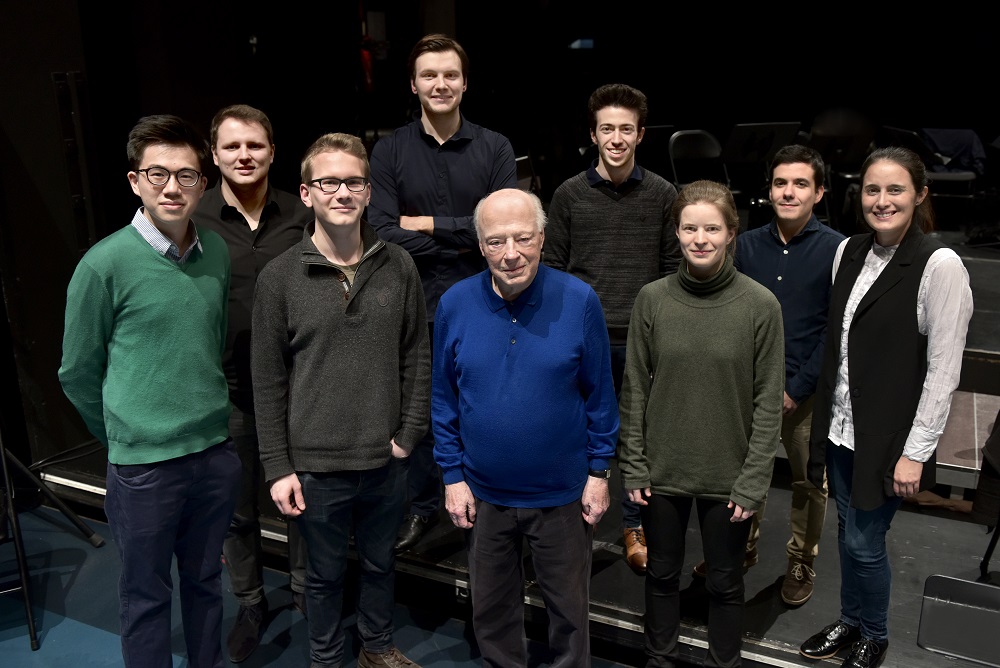

The jewel in a very classy crown, though, had to be a lifetime of conducting experience distilled in Haitink's sparing but pointed words and actions. He's there with his score alongside each conductor, hyper-alert and expressing the nodal points of the work in question, like a sensitive driving instructor with the dual controls. And when he takes over to demonstrate, the sound of the fabulous Lucerne Festival Strings, the effect of instant pianissimos and atmosphere is felt immediately (familiar names among what is in fact a full orchestra include former Scottish Chamber Orchestra leader Alexander Janiczek and Italian first horn Ettore Bongiovanni).  The lucky chosen ones were lovingly enabled and supported (pictured above with Haitink, from left to right: Alvin Ho, Johannes Zahn, Paul Marsovzsky, Vitali Alekseenok, Oren Gross-Tahler, Tabita Berglund, Nuno Coelho and Lina González-Granados). A musician once told me how Haitink likes to let the orchestra play straight through at a first rehearsal so he can adapt to the sounds he hears. So there wasn’t much interrupting going on throughout the six hours of the last day I attended. One of the two German conductors, Paul Marsovzsky, was told to “ignore the mistakes and just let the players have an impression of the piece. You'll be surprised how much falls into place. Then comes the work.” The gentle reprimand, "Paul, be careful! Don't talk too much!", was followed by a succinct enactment of a conductor beginning Beethoven's "Eroica" Symphony and stopping after the first two chords: "Bam. Bam. 'You know Napoleon was...'" (the rest lost in laughter).

The lucky chosen ones were lovingly enabled and supported (pictured above with Haitink, from left to right: Alvin Ho, Johannes Zahn, Paul Marsovzsky, Vitali Alekseenok, Oren Gross-Tahler, Tabita Berglund, Nuno Coelho and Lina González-Granados). A musician once told me how Haitink likes to let the orchestra play straight through at a first rehearsal so he can adapt to the sounds he hears. So there wasn’t much interrupting going on throughout the six hours of the last day I attended. One of the two German conductors, Paul Marsovzsky, was told to “ignore the mistakes and just let the players have an impression of the piece. You'll be surprised how much falls into place. Then comes the work.” The gentle reprimand, "Paul, be careful! Don't talk too much!", was followed by a succinct enactment of a conductor beginning Beethoven's "Eroica" Symphony and stopping after the first two chords: "Bam. Bam. 'You know Napoleon was...'" (the rest lost in laughter).

Other constant advice? On not needing to beat time, starting with Colombian Lina González-Granados: "What you need is to transfer your sound imagination to the orchestra. I watched Carlos Kleiber at the Royal Opera. He didn't beat at all, but the music came through his arms and he communicated. Learn how to motivate what you feel." On trying to get the wiry, energetic Israeli Oren Gross-Tahler to curb his enthusiasm in the finale of Brahms's Second Symphony: "Don't forget this is joyous, not heroic. Don't move around too much. Be cheerful, then you can do this piece with this wonderful orchestra, but don't kill the messenger." And, perhaps the quintessence of the Haitink style, on trusting the players: "It's a beautiful oboe solo [Adam Halicki in the night sounds and perfumes of Debussy's Ibéria]. If you are too slow he suffocates, he can't do what he would like. Trust the orchestra: it has so much experience."  All this might seem the same as interview reflections (I was privileged to have five minutes with the master as the orchestra warmed up for the last session), but there were results: the young conductors' interpretations palpably improved (pictured above: seven of the eight looking on). Not having attended all three days, I missed the long-term changes, but it was heartwarming when Haitink praised Norwegian Tabita Berglund's authoritative way with the Debussy: "that was very good, an enormous surprise to be honest, but this is difficult, totally different from the Brahms." And there could be no greater magic than to see and hear what happened when he took over the opening of Weber's Oberon Overture. That's great conducting, and you can't even tell how the enchantment is achieved.

All this might seem the same as interview reflections (I was privileged to have five minutes with the master as the orchestra warmed up for the last session), but there were results: the young conductors' interpretations palpably improved (pictured above: seven of the eight looking on). Not having attended all three days, I missed the long-term changes, but it was heartwarming when Haitink praised Norwegian Tabita Berglund's authoritative way with the Debussy: "that was very good, an enormous surprise to be honest, but this is difficult, totally different from the Brahms." And there could be no greater magic than to see and hear what happened when he took over the opening of Weber's Oberon Overture. That's great conducting, and you can't even tell how the enchantment is achieved.

It happened, too, throughout Schiff’s concert of C minor Bach and Mozart with the Cappella Andrea Barca, named after a mysterious and possibly immortal 18th century figure whose opera La ribollita bruciata (The Burnt-Bread Soup), Schiff’s programme note told us, “can be considered a pinnacle of Tuscan music history.” Consider "Andrea Barca" again if you’re baffled. This is a crack team of mostly veteran, but still live-wire, players whose responsiveness, as with all top musicians, was a joy to watch.  Both halves of the programme were rich and balanced. In the first, Schiff teamed up with Iranian-German pianist Schaghajeh Nosrati, Bösendorfers head to head, in two major Bach C minor Double Concertos (pictured above) – the second sounding surprisingly muscular as transcribed and transposed from its more familiar D minor version for two violins – framing Mozart’s C minor Serenade for two each of oboes, clarinets, bassoons and horns. Again, the material is better known in its reincarnation, the K406 String Quintet, but it sounded irresistible here, the darker colours so rich and with air around the first-class delivery in the superb acoustics of Lucerne’s KKL Concert Hall.

Both halves of the programme were rich and balanced. In the first, Schiff teamed up with Iranian-German pianist Schaghajeh Nosrati, Bösendorfers head to head, in two major Bach C minor Double Concertos (pictured above) – the second sounding surprisingly muscular as transcribed and transposed from its more familiar D minor version for two violins – framing Mozart’s C minor Serenade for two each of oboes, clarinets, bassoons and horns. Again, the material is better known in its reincarnation, the K406 String Quintet, but it sounded irresistible here, the darker colours so rich and with air around the first-class delivery in the superb acoustics of Lucerne’s KKL Concert Hall.

Even more profound rewards were to be found after the interval. Schiff proved ineffable in the Ricercar a 3 from Bach’s Musical Offering, followed by strings in the Ricercar a 6, and there was a perfect segue into more C minor for the crowning glory, Mozart’s K491 Piano Concerto. Not only was it revelatory to hear the first flute at last – Wolfgang Breimscheid, projecting every one of Mozart’’s miraculous phrases for him – but the sudden excursions into the major brought such balm: perfection indeed from the wind in the second episode of the slow movement and the two major-key finale variations (such wit in the first, such sublimity in the second). As if that weren’t enough, Schiff’s encore solo led us on to the next greatest exponent of smiling through tears, Schubert – the C minor Allegretto of 1827. Again, perfection.  Whether that would be the case the next day seemed doubtful: with very little time to spare between the end of Haitink’s inspirational day and the start of 100 uninterrupted minutes of Messiaen’s Des canyons aux étoiles, I felt like taking the evening off. But it wasn’t just the stiff double espresso that perked me up; the performance of electrifying pianist Hidéko Nagano, consummate horn-player Jean-Christophe Vervoitte, two beguiling percussionists and the combined forces of the Ensemble intercontemporain and Ensemble der LUCERNE FESTIVAL ALUMNI under composer-conductor Matthias Pintscher compelled from first note to last.

Whether that would be the case the next day seemed doubtful: with very little time to spare between the end of Haitink’s inspirational day and the start of 100 uninterrupted minutes of Messiaen’s Des canyons aux étoiles, I felt like taking the evening off. But it wasn’t just the stiff double espresso that perked me up; the performance of electrifying pianist Hidéko Nagano, consummate horn-player Jean-Christophe Vervoitte, two beguiling percussionists and the combined forces of the Ensemble intercontemporain and Ensemble der LUCERNE FESTIVAL ALUMNI under composer-conductor Matthias Pintscher compelled from first note to last.

In this ultimate homage to rocks and skyscapes Messiaen, as usual, seems to go on for two movements too many, and the most compelling dramas are certainly in the middle. For once, though, the musicianship, almost as good to watch as to hear, held the spell. Ann Veronica Janssens’ variously coloured ovals splodged around the hall for three movements added little but did at least lead eyes upwards to the extraordinary KKL ceiling high above us (one of the illuminated movements pictured above by Priska Ketterer).

Saturday was mostly free to explore real nature – the Alps around the lake rival the American canyons – and enjoy the spectacle of Lucerners and fellow visitors sitting out in the warm afternoon sun on the first spring day (the KKL pictured below).

The Festival’s main religious work was Beethoven’s Mass in C, usually overshadowed by the mightier Missa Solemnis, but pleasingly compact and flowingly guided by Jansons, with excellent work from a unified solo quartet – Julia Kleiter, the compellingly involved Gerhild Romberger, Christian Elsner and Florian Boesch – and the superb Bavarian Radio Choir, vivid indeed where the composer is at his most, well, Beethovenian, towards the end.  Then there was a mere 20 minutes to get from the KKL to the city’s intimate theatre, home to both a drama and an opera company – or, more correctly, to the front of the Jesuitenkirche next door, where an extraordinary site-specific staging by Benedikt von Peter of Schumann’s Faust-Szenen began. A chorus in chalky make-up accompanied by blood-smeared children with religious banners began a Lutheran chorale; the doors of the church were flung open and the orchestra under young conductor Clemens Heil struck up the Overture.

Then there was a mere 20 minutes to get from the KKL to the city’s intimate theatre, home to both a drama and an opera company – or, more correctly, to the front of the Jesuitenkirche next door, where an extraordinary site-specific staging by Benedikt von Peter of Schumann’s Faust-Szenen began. A chorus in chalky make-up accompanied by blood-smeared children with religious banners began a Lutheran chorale; the doors of the church were flung open and the orchestra under young conductor Clemens Heil struck up the Overture.

The first half of Schumann’s Goethe selection took place inside the theatre, in near-darkness with the orchestra fed through speakers from the church, as a hallucination of a presumably hospitalised Faust – the parallel with Schumann’s mental illness seemed organic, not contrived – before we moved out into Theaterplatz for the endgame spat between Mephisto (Vuyani Mlinde) and his prey (Sebastian Geyer, coping heroically with the many demands, pictured below centre by Ingo Hoehn in Schumann's final sequence) ricocheting above our heads. The saving of Faust’s soul back inside the church was no simple matter – I wonder if the Jesuitenkirche administration were happy with it – but the ending, with a now-quiescent Faust led out by a carer, proved deeply moving all the same. There’s way more to tell, as I’ve done on my blog; what remains to say is that Faust-Szenen certainly held its head alongside the mainstream Easter Festival happenings as an unforgettable experience.

The saving of Faust’s soul back inside the church was no simple matter – I wonder if the Jesuitenkirche administration were happy with it – but the ending, with a now-quiescent Faust led out by a carer, proved deeply moving all the same. There’s way more to tell, as I’ve done on my blog; what remains to say is that Faust-Szenen certainly held its head alongside the mainstream Easter Festival happenings as an unforgettable experience.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment