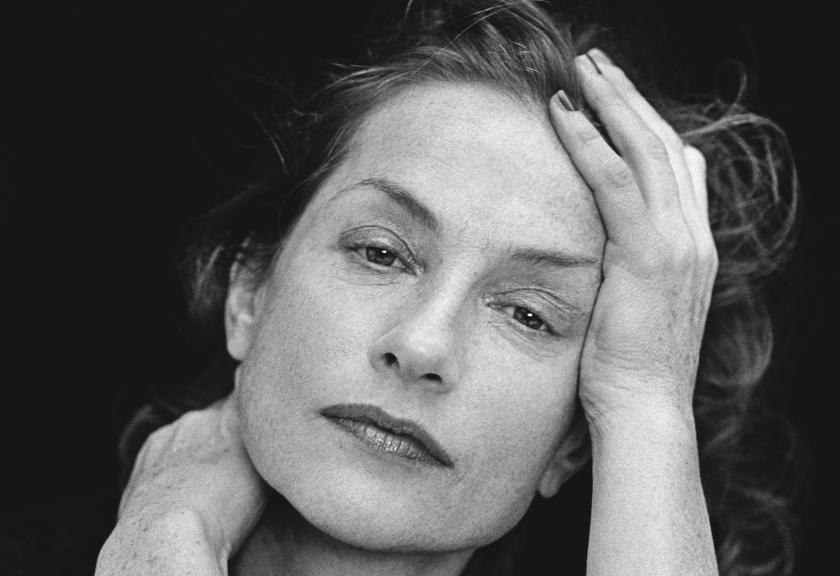

In an era marked by virtue-signalling, it's perhaps no surprise that Isabelle Huppert – a woman who has always gone against the grain – has opted for a little vice-signalling. Unlike other French screen icons, she is not part of the female cohort that railed against the #MeToo movement, yet she has defined herself through roles mired in moral ambiguity, not least as the video games executive who seeks revenge on her rapist in Elle (pictured below). To therefore pair Huppert with her infamously lubricious countryman, the Marquis de Sade, seems like a marriage happily forged in the second circle of Dante's Hell.

It nonetheless still feels like a risk to bring de Sade's visceral violations and contemptuous philosophies to life within the demure setting of the Queen Elizabeth Hall, where Huppert appeared Saturday for a one-off reading. Her chosen texts follow the fates of two very different sisters: the wretchedly virtuous Justine (written by de Sade in 1791) and her opposite of sorts, Juliette, the eponymous heroine of a doorstep tome dating to 1797. For Huppert and the evening's adaptor, Raphaël Enthoven, the question is how to bring to life two contrasting stories in a way that captures their picaresque obscenity and tortured morality without becoming either offensive or absurd.

It nonetheless still feels like a risk to bring de Sade's visceral violations and contemptuous philosophies to life within the demure setting of the Queen Elizabeth Hall, where Huppert appeared Saturday for a one-off reading. Her chosen texts follow the fates of two very different sisters: the wretchedly virtuous Justine (written by de Sade in 1791) and her opposite of sorts, Juliette, the eponymous heroine of a doorstep tome dating to 1797. For Huppert and the evening's adaptor, Raphaël Enthoven, the question is how to bring to life two contrasting stories in a way that captures their picaresque obscenity and tortured morality without becoming either offensive or absurd.

That they succeeded has far more to do with Huppert's performance than Enthoven's adaptation (delivered in French, with surtitles). We hear the actress's voice before she walks defiantly onto the stage, swathed elegantly in a siren red dress. What follows for the most part is an impressionistic swoop through the thieving rapists, licentious murderers, and blasphemous buggering monks encountered by Justine in her failed experiment to prove that virtue is its own reward.

Vice, preaches de Sade, is closer to the natural order: a rhetorical line that delivered iconoclastic oomph at a point when the corruption of the Catholic church was a major concern and in these post-Weinstein days feels inevitably even more contentious.

Huppert's rigorous intelligence teases out the mordant humour and ambiguity in the writing, even when its tone seems as crude as a monk wielding a dildo. (Film critic Pauline Kael once declared that "when [Huppert] has an orgasm, it barely ruffles her blank surface.") And yet, Huppert's steely intensity conveys more in a half-raised eyebrow than most actors can with their whole bodies. Through her delivery, it's possible to see how de Sade's work has been celebrated as well as derided by feminists; how it can be seen to rage against elitist hypocrisy and like a torrent of brutal obscenity itself.

Huppert's chameleonic quality allows her to shift seemingly effortlessly between ages and genders as she animates de Sade's callous cast of grotesques. But unlike her source author, the reading has the feel of operating within tight constraints. There are some strange decisions, too: getting Huppert to dance to Peggy Lee's "Fever" by way of a light interlude seems unnecessary and indulgent. Conversely, microphone glitches never once interrupt the professionalism and insouciance on view centre-stage.

Huppert's chameleonic quality allows her to shift seemingly effortlessly between ages and genders as she animates de Sade's callous cast of grotesques. But unlike her source author, the reading has the feel of operating within tight constraints. There are some strange decisions, too: getting Huppert to dance to Peggy Lee's "Fever" by way of a light interlude seems unnecessary and indulgent. Conversely, microphone glitches never once interrupt the professionalism and insouciance on view centre-stage.

Ultimately, a lack of coherence lets the evening down while nonetheless functioning as a calling-card for an actress whose affinities to the world of de Sade are there to behold. Huppert's Michèle in Elle owes much to his spirit, as does her sadomasochistic Erika Kohut in The Piano Teacher. At the same time, ever-alive to contradiction, Huppert most strongly creates the sense of a woman who refuses to be defined by anybody else, which may be the most important part of her secret after all.

Add comment