With teasing timing, the latest revival of a Tom Stoppard play at the Hampstead Theatre arrived just hours after his funeral, a weird echo of his maxim, “Every exit is an entry somewhere else.” As at its debut in 1995, Indian Ink features a luminous Felicity Kendal, but this time not as perky young poet Flora but in the role of her older sister Eleanor, 65 years on,

The plot follows a favourite Stoppard trajectory, of seeing the past as a puzzle demanding investigation. It’s a strategy he used to best effect in the earlier Arcadia (1993); the resolution of the puzzle here is less enigmatic, less poignant and less satisfying. There is no significant mystery to be “solved”, though there is a twist that sends a minor American academic, Eldon Pike (Donald Sage Mackay), home happy from a visit to Eleanor’s house.

Pike is pursuing biographical nuggets from the life of Flora Crewe, a budding poet in an age that saw women poets as “versifying flappers”. Flora, who had raised the much younger Eleanor, had led a rackety life involving leading bohemians and a scandal that had obliged her to make an appearance in court. Names are dropped at every turn: Flora and Shaw, who got her a walk-on part in Pygmalion; Flora taking tea with Alice B Toklas and Gertrude Stein; Flora and the Sitwells, Charlie Chaplin and Beerbohm Tree. Most important of all, Flora and Modigliani, who painted a portrait of her in the days before his death. Stoppard has great fun cheerily putting his fictitious younger lead in scenarios as if she were an English-rose Zelig.

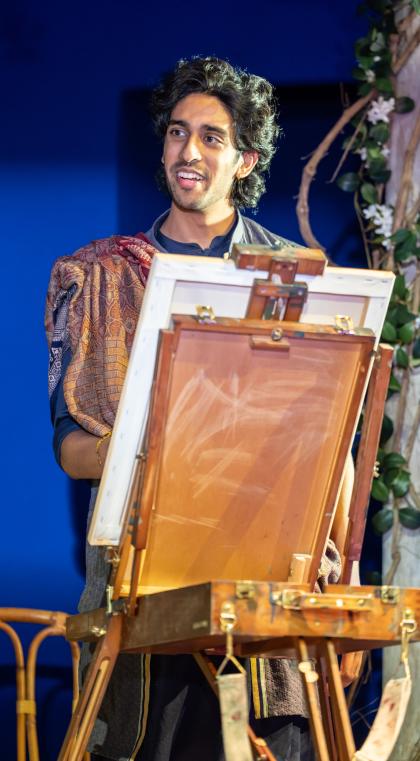

Pike is riveted by all this, naturally. He and Eleanor occupy one half of the stage, in the present day, drinking tea and eating cake in her permanently sunny English garden (inventive set design by Leslie Travers). The other half is set in 1930, in one of the princely states (a Stoppard invention, Jummapur) not governed by the British Empire though slavishly adopting its codes of behaviour. Here Flora (Ruby Ashbourne Serkis) has come for a visit, using her sister’s lover (married, Marxist) as her conduit to the locals. To her little rented cottage comes a local painter, Mr Das (Gavi Singh Chera), as well as a pukka young Brit from the Residency, Captain Durance (Tom Durant Pritchard).

The Indian half of the stage is there to thrash out what, if any, influence the Empire has had on local artists – one particularly tortuous exchange between Flora and Mr Das, the only time the term “Indian ink” crops up, tries to define what an “Indian painter” actually is, given how much in thrall to things European the subcontinent has become. Flora is cross that Mr Das doesn’t paint her as an “Indian” subject. He is besotted with the pre-Raphaelites, whom he sees as fellow storytellers in paint. And besides, he grumbles, the Empire killed Indian painting.

The action then crosscuts between the two zones, the modern-day half catching up with developments in the older one, before the focus swings back to Flora again. Reinforcing the connection between the two zones is Mr Das’s artist son, Anish (Aaron Gill), who also visits Eleanor in England, where he has moved with his English life-model wife. Artefacts from the Indian zone pop up again in the English one, tangible reminders of the ties that bind across the decades, though keeping track of which secretly owned painting is which (one of Flora’s admirers, the local Rajah, also gives her one, a naughty little number from his erotic collection) can get taxing.

Along the way to a kind of denouement there are the usual Stoppardian lay-bys to relax in: the airing of knowledge, the witticisms, the epigrammatic dialogue in which every line is a zinger. This aspect of his writing is delightfully informative and yet anti-dramatic. He can be a dramatist who doesn’t do drama. It also makes you wonder just how much he really disliked academia, whose obsession with footnotes he has Eleanor amusingly disparage. Surely Sir Tom, as intellectually gifted as any prof, was a footnote man too?

Much of the acting here is a trifle broad and shouty, with the exception of Mark Carlisle’s Resident, a punchy Virgil-spouting man of hidden power.

Ashbourne-Serkis is a lively presence though not wholly convincing as a top-flight poet. The poem Stoppard gives her to read out is effective, but her manner is often giddy and glib – you can see why her Flora wasn’t taken entirely seriously by the older men she encountered. And Chera's Mr Das is also too much like the childish locals he complains to Flora about, prone to petulance.

Where Jonathan Kent's production excels, though, is in casting Kendal in a central role. Her beautifully honed ability to land a comic line is key here, where even chatting over tea and cakes can become a weaponised activity deployed against the naive visitor. As in her simple question to Pike, after a robust discussion of the value of Empire, “Victoria sponge or Battenburg?”, which comes layered with a knowing irony. Eleanor is not sentimental about India, and dares to suggest to Pike that the English made it a “proper country”. But her love for the place is also genuine and moving. Stoppard wrote the radio play that gave birth to Indian Ink specifically for Kendal, presumably in recognition of her upbringing there. She has now given him the gift of shining a light on this tricky work.

It’s still a radio play to me, like much of Stoppard’s work, sui generis creations that reward listening and are bursting to share the knowledge he has dug up. In Kendal’s hands, though, this one also registers as wise, and suffused in that generosity of spirit he made his own.

Add comment