Mamzer Bastard, Royal Opera, Hackney Empire review - inert Hasidic music-drama | reviews, news & interviews

Mamzer Bastard, Royal Opera, Hackney Empire review - inert Hasidic music-drama

Mamzer Bastard, Royal Opera, Hackney Empire review - inert Hasidic music-drama

Sludgy orchestral lines and ungainly word-setting in Na'ama Zisser's new opera

Striking it lucky with a successful new opera is a rare occurrence, though every company has a duty to keep on trying.

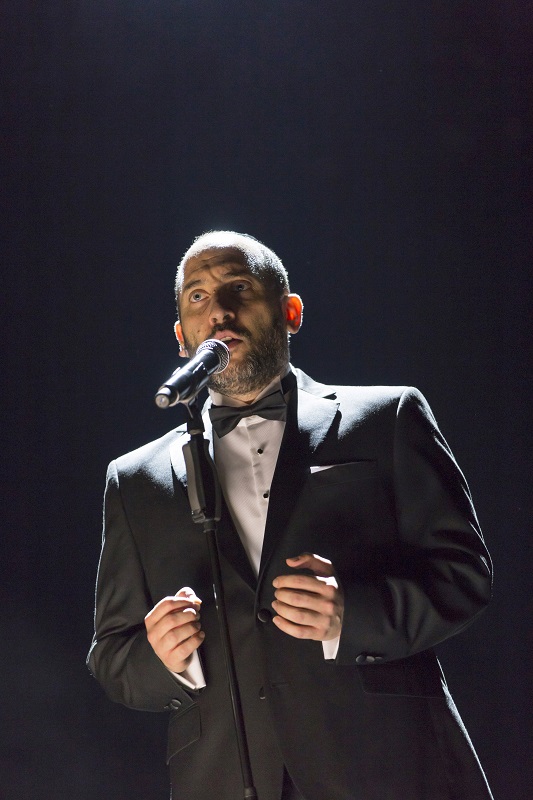

Relatively bearable is the cantorial music framing the action, mostly by other composers – only the last of the seven numbers is by Zisser, and you can guess without having read the programme beforehand since it's much more awkward for the excellent tenor Netanel Hershtik, cantor of The Hampton Synagogue, New York (pictured right), to negotiate. More surprising to read is that Zisser hoped for homogeneity between the religious numbers and her own music-theatre; the contrasts are extreme, and make what in the context of the synagogue might be fitting seem mostly banal.

Relatively bearable is the cantorial music framing the action, mostly by other composers – only the last of the seven numbers is by Zisser, and you can guess without having read the programme beforehand since it's much more awkward for the excellent tenor Netanel Hershtik, cantor of The Hampton Synagogue, New York (pictured right), to negotiate. More surprising to read is that Zisser hoped for homogeneity between the religious numbers and her own music-theatre; the contrasts are extreme, and make what in the context of the synagogue might be fitting seem mostly banal.

The plot, such as it is, underlines with very little tension the heavily signposted revelation. On the eve of his traditional Hasidic wedding, Joel finds that he is indeed his mother's son, but not by his presumed father; the “Stranger” who dogs him is her first husband, presumed dead in the camps (no spoiler there), after whom he's named. That makes Joel the younger not so much a bastard as a “mamzer,” illegitimate in the eyes of Jewish custom because the mother has been married to another man. The drama supposedly unfolds on the streets of New York during the blackout of 13 July 1977.

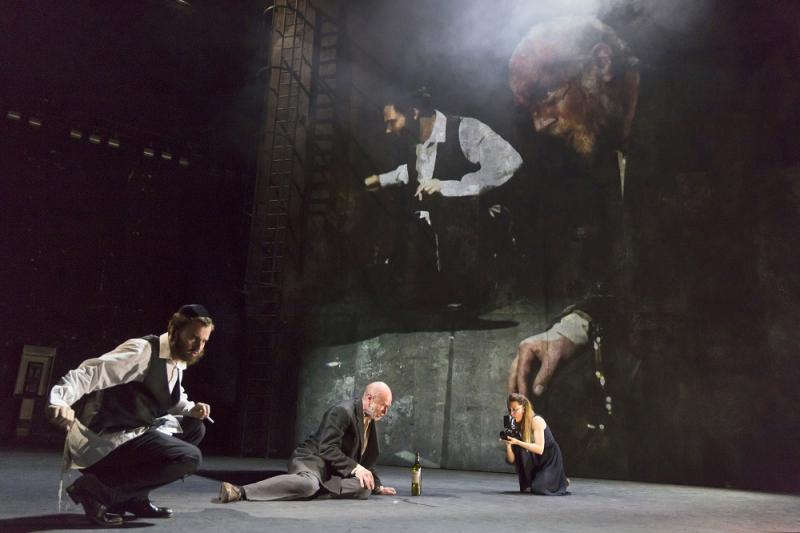

Though this is clearly Joel the younger’s crisis, you'd think it was Apocalypse Now on the streets of New York rather than a matter of personal revelation, the sort of doomy nightmare where you're wading through treacle. The mostly lower-register instruments sink ever downwards in a style which seems at loggerheads with the jerky setting of repetitious text (by Zisser's sister Rachel and Samantha Newton). Whether conductor Jessica Cottis is getting tight results from the Aurora Orchestra ensemble or not is impossible to judge – as is the vocal quality of the five singers actually participating in the drama.  Treble Edward Hyde as young Joel, countertenor Collin Shay as his older self, Gundula Hintz, Robert Burt and Steven Page can't be judged by the same standards that make Hershtik's part in the proceedings more accountable. The ungainly lines are further sabotaged by raspy-edged miking (really necessary against 10 instrumentalists?). The camera held by video designer Pauline Jurzec projecting enlarged images on to a screen – a cliché now in all but the best hands: director Ivo van Hove can still get away with it; Jay Scheib, in charge here, does not – has the further drawback of the lips moving out of synch with the delivery.

Treble Edward Hyde as young Joel, countertenor Collin Shay as his older self, Gundula Hintz, Robert Burt and Steven Page can't be judged by the same standards that make Hershtik's part in the proceedings more accountable. The ungainly lines are further sabotaged by raspy-edged miking (really necessary against 10 instrumentalists?). The camera held by video designer Pauline Jurzec projecting enlarged images on to a screen – a cliché now in all but the best hands: director Ivo van Hove can still get away with it; Jay Scheib, in charge here, does not – has the further drawback of the lips moving out of synch with the delivery.

The possibility of grace after all this torment (Hintz and Shay pictured above) could just about be considered moving in itself, but the real balm comes in a final release from the harsh lights and the monotonous sound pictures. A worthy subject, no doubt, but nothing in its handling inspires confidence in the possibility of future work from this team.

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Comments

Agreed in full. A turgid

I thoughr it was mesmorising

This production is pure

Whatever this critic opinion

Unless my unconscious knows

Unless my unconscious knows something I don't, I assure you you're wrong. I went with nothing but goodwill; it was indeed 'the actual work that did it'. In retrospect, though I wanted to be kind, it might have been better to take the view of Neil Fisher in The Times - that Zisser's supervisors should have stepped in to say that too much was wrong for this to go before the public. The real blame rests with them.

Appalling score and libretto,

What a nonsense write up. I

The way 'to democratise and

The way 'to democratise and refresh the genre' is to write vivid music-theatre that really connects with people and shakes them up. As opera has done, and still does, from Monteverdi through to John Adams. This had an alienating effect upon the young people I spoke to - it certainly isn't going to win any new fans to opera as a form. But you think differently, and that's your prerogative.

The way to refresh the genre

There is indeed no formula;

There is indeed no formula; 'opera', 'music theatre', call it what you will, is a very broad church - but there are criteria, which I tried my best to enlarge upon within the bounds of considering the work itself. No point in expanding on what the score didn't do, but the composer herself objectively failed in one of her objectives (to bring the cantor's music close to her own style). There are certain composers, too, who write deliberately and brilliantly against the grain of the words (Gerald Barry, for one), but that this was bad word-setting. The enervating orchestral textures, which had no correspondence at all with the text, could be justified by themselves, and if there is a future for Zisser, it may well be in instrumental music.