There's surprising and then there's The Lehman Trilogy, the National Theatre premiere in which a long-established director surprises his audience and, in the process, surpasses himself. The talent in question is Sam Mendes, who a quarter-century or more into his career has never delivered up the kind of sustained, smart, ceaselessly inventive minimalism on view here. Add to that a powerhouse cast who demonstrate their own shape-shifting finesse across 3-1/2 giddy and sometimes very moving hours and you have an adrenaline rush of a production that looks unlikely to be limited to the Lyttelton auditorium.

Relating the fortunes of the mighty German-Jewish banking family who came to America in the 19th century only to watch the firm bearing their name crash and burn in the 21st, The Lehman Trilogy superficially evokes such plays as Enron and The Power of Yes only to possess an excitement value all its own. Indeed, high finance turns out to be only one of multiple topics on prismatic view throughout a show that is notably sketchy about what exactly went awry a decade ago (there's no mention of subprime mortgages) but remains fascinating throughout on such subjects as blood ties, assimilation, and the dwindling role of religion in the life of a notable dynasty here seen to go down for the count.

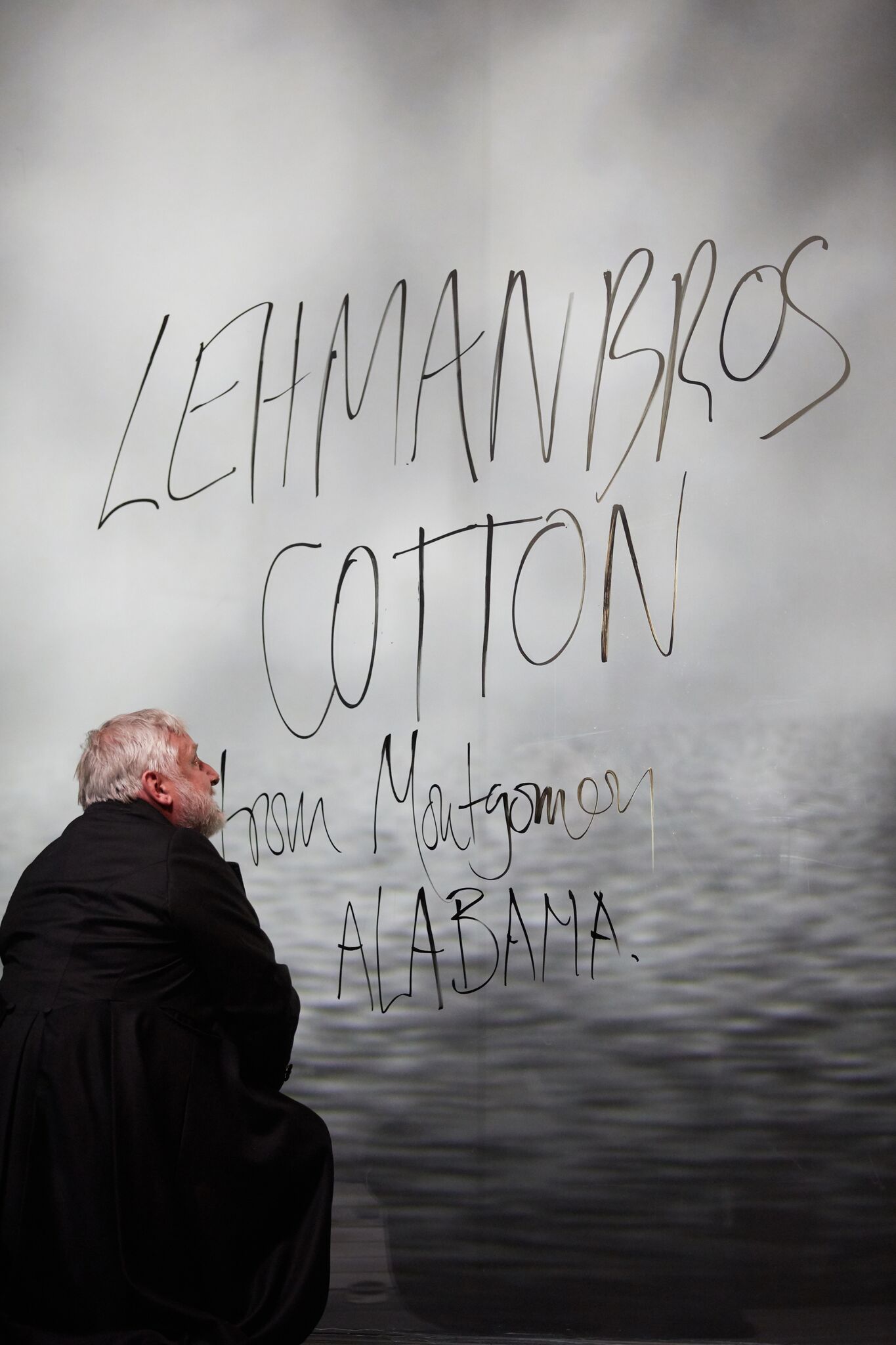

And while one might argue that Ben Power's skilful filleting of Stefano Massini's much-lauded Continental original amounts essentially to an attenuated history lesson delivered by three of the most protean lecturers imaginable, there's nothing remotely dry or academic about the result. Indeed, I can't remember when I last saw a play so indebted to the very notion of the playful. You possibly haven't lived – in theatrical terms, that is – until you've seen Simon Russell Beale (a mainstay of Mendes's career) playing a wizened rabbi, or Adam Godley as one of a sequence of brides marrying into a family that puts its men first, or Ben Miles (pictured above) starting out as the de facto hard man, Emanuel, of the three Lehman brothers only to morph in time into that character's three-year-old nephew, Herbert. (All three actors pivot between ages, and generations, with consummate ease.)

And while one might argue that Ben Power's skilful filleting of Stefano Massini's much-lauded Continental original amounts essentially to an attenuated history lesson delivered by three of the most protean lecturers imaginable, there's nothing remotely dry or academic about the result. Indeed, I can't remember when I last saw a play so indebted to the very notion of the playful. You possibly haven't lived – in theatrical terms, that is – until you've seen Simon Russell Beale (a mainstay of Mendes's career) playing a wizened rabbi, or Adam Godley as one of a sequence of brides marrying into a family that puts its men first, or Ben Miles (pictured above) starting out as the de facto hard man, Emanuel, of the three Lehman brothers only to morph in time into that character's three-year-old nephew, Herbert. (All three actors pivot between ages, and generations, with consummate ease.)

The performers' lightning-flash dexterity must have been painstakingly arrived at in the rehearsal room in a production that couldn't be more different from the capaciously-cast, hyper-realist The Ferryman, with which Mendes recently scooped several Best Director awards.

And while the totality of this play tells a sobering story of the self-devouring impulses of capitalism, the production forsakes hectoring to arrive at something more mournful on the one hand – not for nothing does the programme evoke yet another meditation on, yes, the American dream – and flintier, as well. One clocks the fall-off between Russell Beale's Bavarian-born Henry Lehman at the start speaking in awestruck tones of an "idea of America" made flesh ("a magical music box" is how he perceives this brave new world before him) and the blood, literal and figurative, that has been spilled by play's end, thereby triggering a financial meltdown whose repercussions linger on to this day.

The production evokes comparisons aplenty, starting with a historical phantasmagoria like EL Doctorow's freewheeling Ragtime, even if race – a crucial component to that earlier American chronicle – doesn't get much of a look-in here. And it's no surprise that Nick Powell's original music (played live to the side of the stage) at times evokes the plaintive lushness of Nino Rota, The Lehman Trilogy approximating in synoptic form something of the thematic breadth of The Godfather, which Rota scored. Nor is sobriety allowed to prevail for long: the production contains in passing a potted history of classical music for the ages and finds an apt descriptor near the start for the three brothers, who represent an equivalent head (Henry), arm (Emanuel), and, um, potato (Mayer), even if the final image over time is somewhat overworked.

The production evokes comparisons aplenty, starting with a historical phantasmagoria like EL Doctorow's freewheeling Ragtime, even if race – a crucial component to that earlier American chronicle – doesn't get much of a look-in here. And it's no surprise that Nick Powell's original music (played live to the side of the stage) at times evokes the plaintive lushness of Nino Rota, The Lehman Trilogy approximating in synoptic form something of the thematic breadth of The Godfather, which Rota scored. Nor is sobriety allowed to prevail for long: the production contains in passing a potted history of classical music for the ages and finds an apt descriptor near the start for the three brothers, who represent an equivalent head (Henry), arm (Emanuel), and, um, potato (Mayer), even if the final image over time is somewhat overworked.

One wonders, too, how this iteration of Massini's play could possibly be published, given its dependence on a level of invention that extends beyond its cast to include Es Devlin's translucent whirligig of a set, which gets written on (see above) as the Lehman fortune evolves from cotton through to coffee and builds from there, all the while moving north from Alabama to the fabled New York which Emanuel, in particular, holds dear. Luke Halls's video design encompasses the literal and the figurative and numerous stops in-between, not least a sequence of visually kaleidoscopic nightmares that cracks open these paragons of success to reveal the more panicky inner lives contained within.

And even as the narrative loops back on itself, ending where it began with the firm's calamitous collapse, the self-evident thrill circles back to a cast who seem genuinely to exult in the opportunities provided them. I won't soon forget Godley as the 77-year-old Bobbie Lehman doing "the twist" as the others join in, nor Miles revelling earlier on in a world in which buying and expenditure are as instinctual as breath. The peerless Russell Beale is a flirty divorcée (!) one minute, the governor of Alabama the next. And when he stands all but motionless centre-stage to look with wonder into a future that will come to grief, the actor in an instant contains multitudes, as does a stripped-back production amid which he and his colleagues stand very tall.

Add comment