Salome, English National Opera review - a not so terrible stillness | reviews, news & interviews

Salome, English National Opera review - a not so terrible stillness

Salome, English National Opera review - a not so terrible stillness

Inertia kills strong stage pictures, decent singing and a bejewelled orchestra

Sibling incest among the symbolic clutter of the Royal Opera Ring on Wednesday, last night necrophilia and a bit more incest – mother and daughter this time, courtesy of the director's imagination – in a stone-cold ENO Salome.

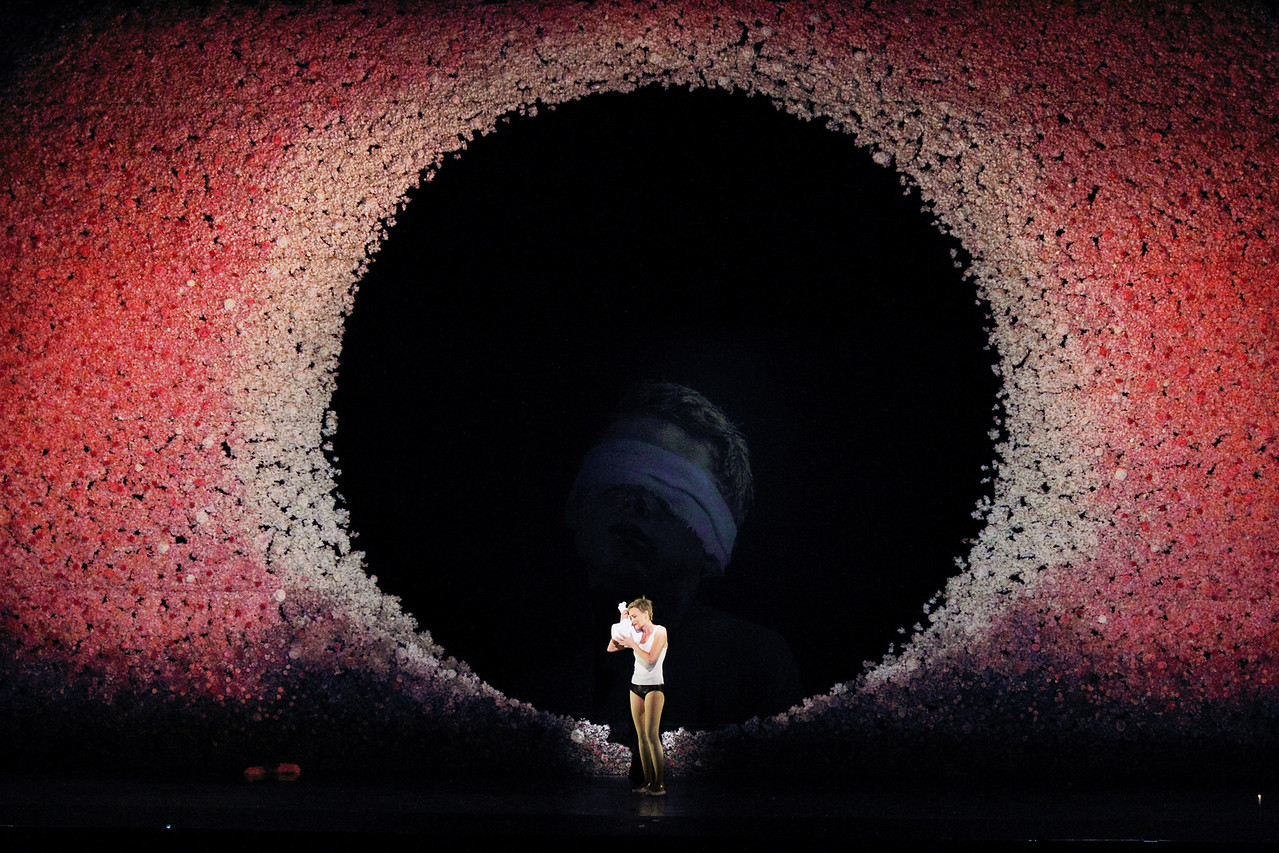

It seemed as if we might get that at first. Princess-smitten Narraboth (the clarion-toned Stuart Jackson) is in a cordon at a celebrity showing, the moon perhaps the writhing figure in the tank above, the object of his desire (the visually mesmerising Salome of Allison Cook) sidling in unnoticed at first, near-motionless, slyly implying terrible things - not least a phial for Narraboth which turns out to contain poison; this girl is death-fixated from the start. The stage opens up for the man she really wants to see, imprisoned John the Baptist (David Soar, a fine bass, but the role calls for security in the baritonal heights), under a glaring grid of lights and a sheet from which at first only two feet in pink shoes are poking out (for what? Blood? Androgyny? A set-up for the My Little Pony colours to come?). It's one of many strong stage pictures. But as Strauss begins to turn the screw with Salome's fascination for the forbidden, neither Jacobs nor conductor Martyn Brabbins meet him even half way.

The orchestra glitters, woodwind solos helpfully clear down to the heckelphone or bass oboe; but the serpentine mass never uncoils or strikes. Brabbins, no man of the theatre on this evidence in his opening gambit as ENO's Music Director, ensures perfect balances within the orchestra, if not between players and singers, while there's good co-ordination with a note-perfect cast. That isn't enough. There was a thousand times more electricity in the Prom collaboration between Donald Runnicles and Nina Stemme. Which is not to say that Salome can't triumph in its ideal form, the fusion of music and stage drama. Any of the previous London productions, above all David McVicar's at Covent Garden, has found the essential sparks at some point in the evening.  Jacobs isn't the first to suggest that Salome and Jokanaan never come close to contact or really seeing each other; Luc Bondy did that so much more theatrically in the Royal Opera production before McVicar's. It's a strong touch to have Jokanaan's mouth projected onto the wall via a kind of video muzzle attached to the prisoner, though we need to see the eyes, too, the hair, the flesh. This Salome's auto-eroticism as she apparently apostrophises her own body isn't so much compelling as chilly, and while mezzo Cook gets all the notes, there's little colour, and certainly not enough power to ride an increasingly fleshy orchestra. If her Barbie blonde ponytail suggests female objectification at Herod's court, the arrival of the dysfunctional family offers no further clues to her dysfunction. There's no progression from princess pettishness to a thwarted lust that turns deadly-obsessive. It's all concept, well enough realised through Marg Horwell's designs and Lucy Carter's lighting, but without enough physicality demanded from the singers.

Jacobs isn't the first to suggest that Salome and Jokanaan never come close to contact or really seeing each other; Luc Bondy did that so much more theatrically in the Royal Opera production before McVicar's. It's a strong touch to have Jokanaan's mouth projected onto the wall via a kind of video muzzle attached to the prisoner, though we need to see the eyes, too, the hair, the flesh. This Salome's auto-eroticism as she apparently apostrophises her own body isn't so much compelling as chilly, and while mezzo Cook gets all the notes, there's little colour, and certainly not enough power to ride an increasingly fleshy orchestra. If her Barbie blonde ponytail suggests female objectification at Herod's court, the arrival of the dysfunctional family offers no further clues to her dysfunction. There's no progression from princess pettishness to a thwarted lust that turns deadly-obsessive. It's all concept, well enough realised through Marg Horwell's designs and Lucy Carter's lighting, but without enough physicality demanded from the singers.

Michael Colvin's Herod and Susan Bickley's Herodias, well cast, would make more impact in a more interactive production. I see the beginnings of good ideas that could work with a bit of theatrical alchemy, not least the multiple Salome-Barbies in the dance, Cook's protagonist mostly deadly still and revealing a more powerful short haircut beneath the wig at the climax. And there's clearly intent in Jacobs' pre-empting of what should in fact happen later: the necrophilia applied early on to Narraboth's corpse (pictured above: Soar, Cook and Jackson), an unbinding of breasts in the supposed confrontation with Jokanaan and a giant headless not-so-little pony with floral entrails.  The necessary catharsis, though, the unique mixture of horror and nostalgia which is, God knows, powerful enough with Salome's kissing of a severed head dripping blood so long as it looks real enough, never happens. Richard Jones has understood how to make a head in a cardboard box or a plastic bag uniquely creepy; this is not (pictured above). And the kiss – well, I've implied it already but if you really intend to go and don't want a spoiler, I'll stop there. Cook is a compelling actor, but vocally several sizes too small for Strauss's all-important Liebestod. One hears and sees unmoved. And in a masterpiece as visceral as Salome, that's not good enough.

The necessary catharsis, though, the unique mixture of horror and nostalgia which is, God knows, powerful enough with Salome's kissing of a severed head dripping blood so long as it looks real enough, never happens. Richard Jones has understood how to make a head in a cardboard box or a plastic bag uniquely creepy; this is not (pictured above). And the kiss – well, I've implied it already but if you really intend to go and don't want a spoiler, I'll stop there. Cook is a compelling actor, but vocally several sizes too small for Strauss's all-important Liebestod. One hears and sees unmoved. And in a masterpiece as visceral as Salome, that's not good enough.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

The Makropulos Case, Royal Opera - pointless feminist complications

Katie Mitchell sucks the strangeness from Janáček’s clash of legalese and eternal life

The Makropulos Case, Royal Opera - pointless feminist complications

Katie Mitchell sucks the strangeness from Janáček’s clash of legalese and eternal life

First Person: Kerem Hasan on the transformative experience of conducting Jake Heggie's 'Dead Man Walking'

English National Opera's production of a 21st century milestone has been a tough journey

First Person: Kerem Hasan on the transformative experience of conducting Jake Heggie's 'Dead Man Walking'

English National Opera's production of a 21st century milestone has been a tough journey

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft