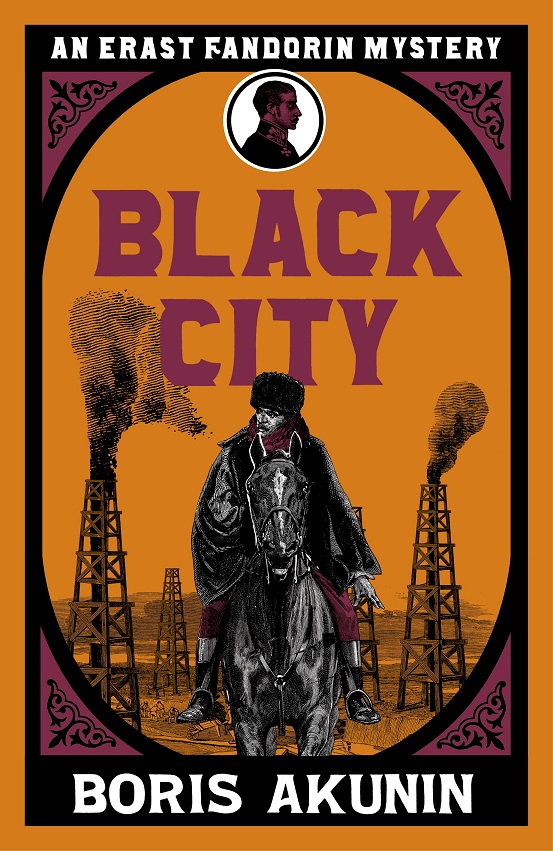

Boris Akunin: Black City review - a novel to sharpen the wits | reviews, news & interviews

Boris Akunin: Black City review - a novel to sharpen the wits

Boris Akunin: Black City review - a novel to sharpen the wits

Tsarist agent extraordinaire Fandorin confronts revolutionary upheaval on the Caspian

It is 1914 – a fateful year for assassinations, war and revolution.

This well-travelled Muscovite is visiting Yalta to pay homage to the memory of his hero, Chekhov, thus already utilising the mix of real history and fiction that is characteristic of Akunin’s novels, which play with several genres simultaneously. This means, of course, that the reader cannot necessarily untangle fact and imagination, as the multilingual Fandorin and his Japanese manservant Masa, once a gangster, weave their way through what confronts them. Fandorin keeps a daily aphoristic diary, while Masa trains his master in useful physical skills, including the ability to move silently.

The stage is set. In Yalta, Fandorin is unexpectedly set up to unknowingly facilitate the assassination of the Tsar’s security chief, Spiridonov. In one of those masculine issues around honour, Fandorin is in his own eyes almost mortally insulted by the plot’s instigator, a mysterious terrorist whose pseudonym is Odysseus. An ultimate confrontation looms...

The stage is set. In Yalta, Fandorin is unexpectedly set up to unknowingly facilitate the assassination of the Tsar’s security chief, Spiridonov. In one of those masculine issues around honour, Fandorin is in his own eyes almost mortally insulted by the plot’s instigator, a mysterious terrorist whose pseudonym is Odysseus. An ultimate confrontation looms...

On the flimsiest of clues, our irritated super-sleuth sets off on the trail of his mischievous rival. Fandorin ploughs on, trainwards, to Baku, on the Caspian Sea; the newly rich and vastly corrupt Russian oil city is responsible for a huge proportion of the world’s output of the indispensable fossil fuel. There he is saved only by some nifty feinting from being casually murdered on the arrival platform.

There are continual flashes of the unexpected: Masa has never seen observant Muslim women before, and takes their yashmaks to indicate that they are deliberately covering up their ugliness. It transpires that Fandorin’s common-law wife, Clara Moonlight, whom he amusingly despises, is also in Baku, starring in a movie, The Love of the Caliph; descriptions of early filmmaking are as much a part of this overwhelming patchwork of a novel as are early cars – Daimlers figure especially – as well as the horrors of the early oil industry, including seas on fire. Meanwhile Sarajevo impinges, and Fandorin, ignorant of that conflagration to come, assumes that the Europeans will smooth everything over.

In a brilliant, terrifying interplay of capitalist greed and competition in overt and covert warfare between those who own the means of production and those who can organise politically orchestrated strikes, the real spectre of political revolution is obscured by distractions. As bullets fly from Mausers and other well described weaponry, the faithful Masa is badly wounded. Armenians are the villains to the unlikely allies and conspirators who are in a loose network infiltrated by Fandorin. He is the target of at least three assassination attempts and an early horrible incident has him, bound hand and foot, thrown into an oil well to drown in the stuff. A very clever thug, Hasim, becomes, inexplicably, a major ally, a comrade in arms – and there are plenty of arms. As in a Jacobean tragedy, the reader might be helped by a cast listing as the narrative reels between Eastern and Western cultures that mix and match in the oil-fuelled conspiracies and rivalries of Baku.

Nothing is as it seems, and the dynamics of the novel involve Fandorin figuring out the pattern in a shifting kaleidoscope. Names change for the same person, in keeping with patronymics, nicknames, disguises. Interleaved are detailed and evocative descriptions of desolate landscapes and an extraordinary and fantastically rich city, with ugliness and grandeur intermingled. There is a very grand winter casino, an equally grand summer casino, grand hotels, palaces, and horrific neighbourhoods and hideous industry, all meticulously and atmospherically described. A Persian eunuch, Zafar, and a German tutor are involved in the household of a female Muslim oil entrepreneur, Madam Saadat Validbekova, the widow of an ancient oil millionaire, whose emotional life is allied to her young son Tural who – natch – is kidnapped. Not by the Bolsheviks but as part of a commercial war, her enemy a plutocrat called, perhaps, Artashshov.

The seemingly politically motivated strike will cripple oil production; he who controls the strike, will control oil, and whoever that is will be the most powerful person in the Russian Empire. You may have trouble keeping track… In the midst of all the complex mayhem, occasional brutality and an increasing body count, realpolitik flickers in and out; this is a novel to sharpen the wits. Fandorin is 58, and has spent, he tells us, 40 years killing: now the leaders from St Petersburg come to Baku to ask him to go to Vienna and stop the coming war; the revolutionaries are more prescient about the coming carnage and what it means for their cause. Happy endings – what those might constitute is not at all certain – are not in the least assured, but the journey is amazing.

- Black City by Boris Akunin, translated by Andrew Bromfield (Weidenfeld & Nicolson £20, Kindle edition £9.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Add comment