Cate Haste: Passionate Spirit - The Life of Alma Mahler review - a racy life pacily narrated | reviews, news & interviews

Cate Haste: Passionate Spirit - The Life of Alma Mahler review - a racy life pacily narrated

Cate Haste: Passionate Spirit - The Life of Alma Mahler review - a racy life pacily narrated

The creative Viennese soclalite who obsessively nurtured masterpieces by others

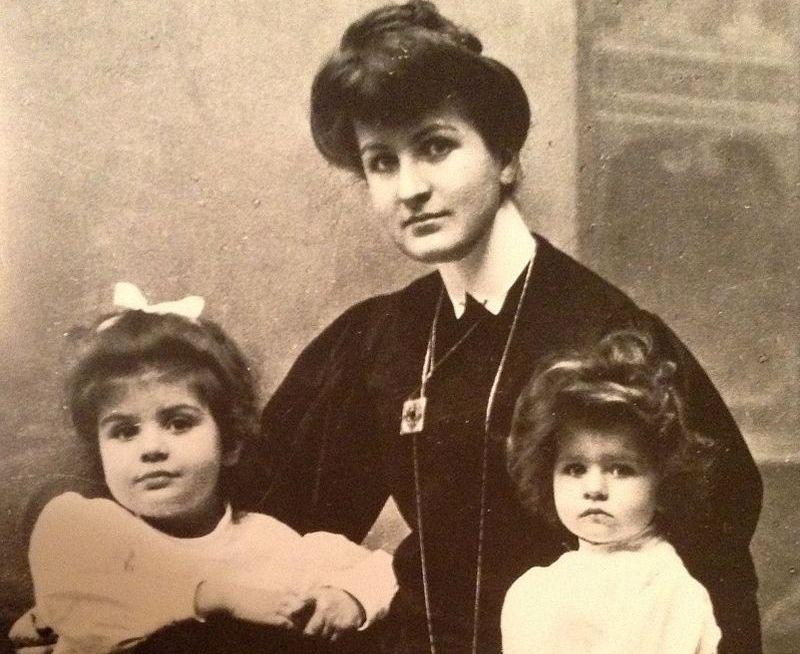

Charismatic, full of vital elan to the end, inconsistent, fitfully creative, a casually anti-semitic Conservative Catholic married to two of the greatest Jewish artists, Alma Mahler/Gropius/Werfel née Schindler can never be subject to a boring biography.

There's little new here, despite Haste's claims of "deep delving" (somewhat undermined by immediate acknowledgment of help from researchers and translators - inevitably disdained by those of us compelled to be lone-wolf biographers). It's good to read around the years with Gustav Mahler, who all too typically told his new wife that there wasn't room for two composers in the marriage but in his desperation to keep Alma from her new love Walter Gropius finally gave encouragement to her song-writing just before he died.

Gustav Klimt, her first great love, told her she was "spoilt by too much attention, conceited and superficial". In him, Zemlinsky and Mahler she obviously sought a replacement for the artist father she revered, who died when she was 13 years old (one revelation here, drawn from Marie Bonaparte's unpublished diary manuscript as reproduced in Stuart Feder's Gustav Mahler: A Year in Crisis, tells us more about Mahler's meeting with Freud and the great psychonalyst - rather than "psychotherapist," as Haste puts it - enlightening him about his mother-fixation).

After Mahler's death, Alma went for younger men: the terrifying and sado-masochistic Oscar Kokoschka, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and the most popular Austrian-based author of his time, Franz Werfel, with whom she stayed as her charms faded and for whom she made practical moves of self-sacrifice, showing remarkable fortitude in their escape from the Nazis through France - including some time in Lourdes, which gave Werfel inspiration for The Song of Bernadette - to Spain, Portugal and on to America.

After Mahler's death, Alma went for younger men: the terrifying and sado-masochistic Oscar Kokoschka, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and the most popular Austrian-based author of his time, Franz Werfel, with whom she stayed as her charms faded and for whom she made practical moves of self-sacrifice, showing remarkable fortitude in their escape from the Nazis through France - including some time in Lourdes, which gave Werfel inspiration for The Song of Bernadette - to Spain, Portugal and on to America.

The language of Alma's diaries and her exchanges with many of her lovers show a gushing romantic delusion that never gave way to real self-knowledge. She is refreshingly, occasionally embarrassingly, frank about her sexual experiences, dangerously ignorant of the political sphere - which led to huge clashes with the politically engaged left-winger Werfel - and sometimes risibly egotistical about it (of the First World War: "I sometimes imagine that I was the one who ignited this whole world conflagration in order to experience some kind of development or enrichment - even if it be only death"). She later repented her admiration of "genius" Hitler and tried to airbrush it out of her reminiscences and collection of letters, but for all that she never estranged most of the members of the Jewish circle in which she mixed, both in Vienna and Los Angeles.

Something of her flightiness is captured in Tom Lehrer's masterful song "Alma":

Perhaps the most devastating verdict on Alma's ability to move on came from her daughter by Gropius, Manon - the same "angel" to whom Berg dedicated his Violin Concerto - as unflinchingly recorded by the mother in her diary: " 'Let me die in peace...You'll get over it, the way you get over everything', and as if to correct herself, 'like everyone gets over everything' ". It can't have been easy: Manon was the third child she lost. And who are we to judge?

As for Alma's work as a composer, Haste offers no guidance on the surviving songs - much was destroyed in the Second World War - until the end, where she concludes rather weakly with "her own music is her lasting, and living, legacy". In fact the songs are good, but inevitably not on the level of her first husband's work (what is?) They have found their place in performance, and their level: worth hearing, but hardly genius. Had Alma been a born creator, she would have persisted with her work. Clearly she was an excellent pianist, even if it's unlikely that, as Haste claims, she played entire Wagner operas from memory - only of the composer Enescu, a phenomenal intelligence, can that be true. In all else she was, as one observer commented, a generalist with a vague grasp of facts.

The narrative is racy, with clear fill-ins on the historical background, but a few German names are misspelt (about a dozen), suggesting a lack of engagement with the language (and Haste uses mostly secondary sources). A good popular biography, though, and beautifully presented, as usual, by Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Passionate Spirit - The Life of Alma Mahler by Kate Haste (Bloomsbury Publishing, £26)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Add comment