Death of a Salesman, Piccadilly Theatre review - galvanising reinvention of Arthur Miller's classic | reviews, news & interviews

Death of a Salesman, Piccadilly Theatre review - galvanising reinvention of Arthur Miller's classic

Death of a Salesman, Piccadilly Theatre review - galvanising reinvention of Arthur Miller's classic

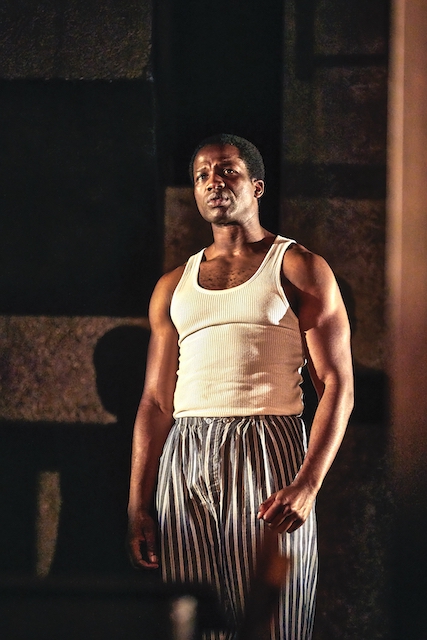

Wendell Pierce confirms a performance as exciting as any this theatrical year

It is 70 years since Willy Loman first paced a Broadway stage; 70 years since audiences were sucked into the vortex of a man trying to live America’s capitalist dream only to see his life crash and burn around him.

Director Marianne Elliott – who so brilliantly re-energised Sondheim’s Company last year by making the male protagonist a woman – collaborates with Miranda Cromwell to create a production that dynamically interweaves expressionism and naturalism. One of the reasons, of course, that it works so well to make Miller’s narrative racially charged is that his original inspiration for the white Willy Loman came from Brooklyn. Here the dynamic is subtly shifted from the start as members of the neighbourhood come together to sing the melancholic gospel hymn "When the Trumpet Sounds".

It's a letter from Truman’s America to Trump’s America

Characteristically for an Elliott production, every aspect of the design – both visual and aural – amplifies the emotional pull of the central performances. On Ann Fleischle’s clever minimalist set nothing entirely obeys gravity. Window and door frames are suspended on strings that enable them to be raised or lowered, similarly the Lomans’ kitchen table and chairs can sit comfortably on the ground one moment and ascend to the rafters the next. It’s an all too appropriate way of summing up the perspective of a man for whom the entire world seems to be flying out of control.

Wendell Pierce proves once more why his performance has been seen as one of the most exciting of the theatrical year. His Loman is a man trapped – by the lies society has told him about what he can achieve, and by the lies he has told himself. Pierce heartbreakingly embodies a man who is tortured by his contradictions. He is simultaneously filled with optimism and despair, pride and loathing, rumbles of macho strength and child-like weakness.

A particularly strong aspect of this endlessly galvanising production is Carolyn Downing’s sound design, which combines with Aidleen Malone’s lighting to add impact to Loman’s increasing inability to distinguish between past and present. The bubble of his delusions is enshrined most strongly in the expectations he imposes on his eldest son Biff. Here, when he remembers his sons’ childhood the scenes are replayed as if through a freeze-frame of snapshots. As the click and fizz of an old-fashioned camera resonates through the theatre, Pierce recoils, as if in pain: in this way, brilliantly, the distillation of memory through technology adds to the sense of how an idealised past is corrupting the wretched present.

The racial tension becomes most manifest in the upsetting scene where the exhausted Loman goes to beg his employer, Howard, to give him a desk job. In the best theatrical productions, there are moments where one tiny gesture can provoke an emotional earthquake. That comes when Matthew Seadon-Young’s Howard drops a cigarette lighter and Pierce is forced to stoop to pick it up. It would be a humiliation on any level: here a history in which such casual humiliations have all too easily escalated into violence makes it resonate still further. In that moment we see the beginning of the end.

Yet this is a production that also shows the play’s enduring power through its themes of over-charged parental expectations, the myths that families create for themselves, and the tragedy of watching anyone you care for slowly destroying themselves. It’s a brilliant reinvention, but it remains a story for anyone struggling to better themselves: it's a letter from Truman’s America to Trump’s America, one that shows how while everything changes at the same time nothing changes.

- Death of a Salesman at the Piccadilly Theatre to January 4, 2020

- More theatre reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

Add comment