The Rise and Fall of The Clash, Now TV review - London falling | reviews, news & interviews

The Rise and Fall of The Clash, Now TV review - London falling

The Rise and Fall of The Clash, Now TV review - London falling

Absorbing blow-by-blow account of the great British punk band’s destruction

Open-mouthed incredulity is a reasonable reaction to this 2012 documentary on one of the UK’s prime punk-spawned bands, available on catch-up via streaming service Now TV’s tie-in with Sky Arts. There’s not much “rise” but there’s an awful lot of “fall” in The Rise and Fall of The Clash.

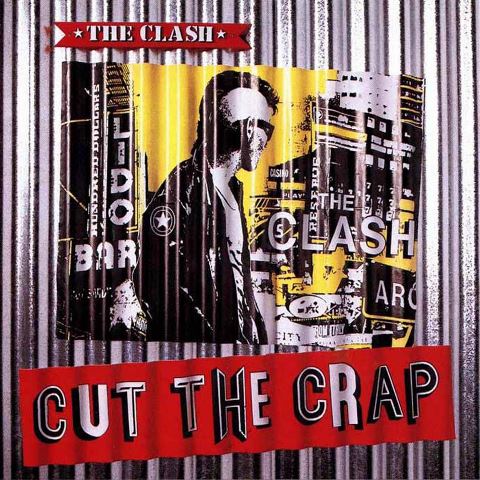

After coalescing between April and June 1976 in the slipstream of the Sex Pistols, The Clash fell apart in November 1985. The end came at the same time as the release of what became their final album, Cut The Crap. Reviewing it for the music weekly Melody Maker, Adam Sweeting said “Guess what? It’s CRAP! And it doesn’t cut it. Football chants, noises of heavy meals being regurgitated over pavements and carpets and a mix Moulinex would be ashamed of. Ugly? It’s painful.”

Cut The Crap was indeed awful. It was not by Mick Jones, Topper Headon, Paul Simonon and Joe Strummer – the band which had become well known. It was not even made by the unlauded final version of The Clash: Simonon and Strummer plus Pete Howard, Nick Sheppard and Vince White. It was created by the band’s manager Bernard Rhodes in Germany from unfinished demo tapes. Howard, the terminal-drive drummer, was replaced by clunky programmed rhythms. Bassist Simonon was supplanted by former Blockhead Norman Watt-Roy. Rhodes, a non-musician who had never produced a record before, happily added his own synth parts.

Cut The Crap was indeed awful. It was not by Mick Jones, Topper Headon, Paul Simonon and Joe Strummer – the band which had become well known. It was not even made by the unlauded final version of The Clash: Simonon and Strummer plus Pete Howard, Nick Sheppard and Vince White. It was created by the band’s manager Bernard Rhodes in Germany from unfinished demo tapes. Howard, the terminal-drive drummer, was replaced by clunky programmed rhythms. Bassist Simonon was supplanted by former Blockhead Norman Watt-Roy. Rhodes, a non-musician who had never produced a record before, happily added his own synth parts.

With Cut The Crap as its full stop, The Rise and Fall of The Clash begins with a brief summary of how they reached their peak and speedily becomes a blow-by-blow account of the band limping to its sorry end over the final four years. Jones features, as do Howard, Sheppard and White. Howard’s predecessor and returning early Clash drummer Terry Chimes is also interviewed. Many other talking heads distractingly crop up: some central to the story, most less so. Simonon and Headon crop up in archive clips. So does Strummer, who died in 2002. Amazingly, this a Clash documentary which lacks perennial Clash pundit Don Letts.

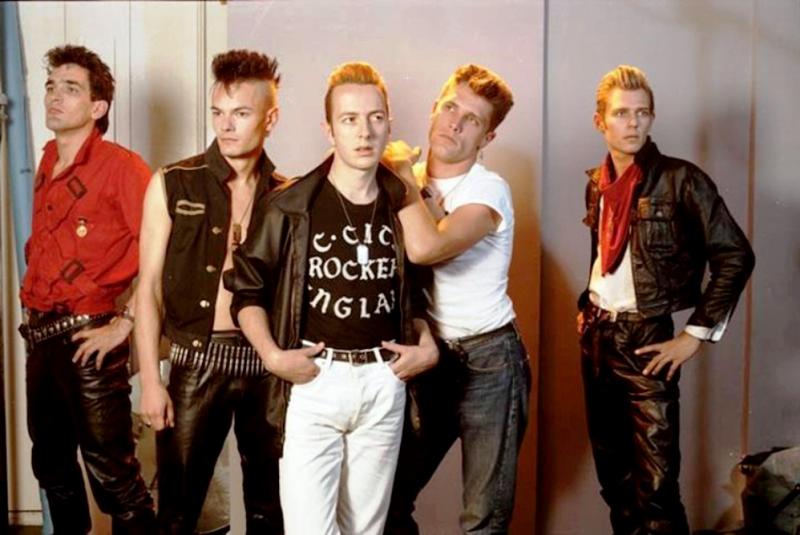

The pitiful details of the demise of The Clash were first laid out in Marcus Gray’s 1995 book Last Gang in Town: The Story and Myth of The Clash. The Rise and Fall of The Clash doesn’t have the context, exposition and nuance of the printed page but cherry picks from what Gray uncovered to present the narrative as a series of bullet points. The milestones begin clocking up from early 1981, when the band’s original manager Bernard Rhodes – who had been sacked in October 1978 – is re-employed. En route to the journey's end, Strummer goes AWOL after which drummer Topper Headon leaves in April 1982. Level-headed early Clash drummer Terry Chimes returns to replace Headon and, in turn, is replaced by Howard. With Strummer’s agreement, Rhodes ejects Mick Jones in September 1983 (Rhodes had form there as he tried in 1978 to replace Jones with former Sex Pistol Steve Jones. The film doesn’t mention this). Two guitarists would fill Jones’ shoes: Vince White and Nick Sheppard. The final five-piece Clash, it’s pointed out, wore naff high-street punk garb and despite putting on a good show was, in essence, a Clash revival band.

The pitiful details of the demise of The Clash were first laid out in Marcus Gray’s 1995 book Last Gang in Town: The Story and Myth of The Clash. The Rise and Fall of The Clash doesn’t have the context, exposition and nuance of the printed page but cherry picks from what Gray uncovered to present the narrative as a series of bullet points. The milestones begin clocking up from early 1981, when the band’s original manager Bernard Rhodes – who had been sacked in October 1978 – is re-employed. En route to the journey's end, Strummer goes AWOL after which drummer Topper Headon leaves in April 1982. Level-headed early Clash drummer Terry Chimes returns to replace Headon and, in turn, is replaced by Howard. With Strummer’s agreement, Rhodes ejects Mick Jones in September 1983 (Rhodes had form there as he tried in 1978 to replace Jones with former Sex Pistol Steve Jones. The film doesn’t mention this). Two guitarists would fill Jones’ shoes: Vince White and Nick Sheppard. The final five-piece Clash, it’s pointed out, wore naff high-street punk garb and despite putting on a good show was, in essence, a Clash revival band.

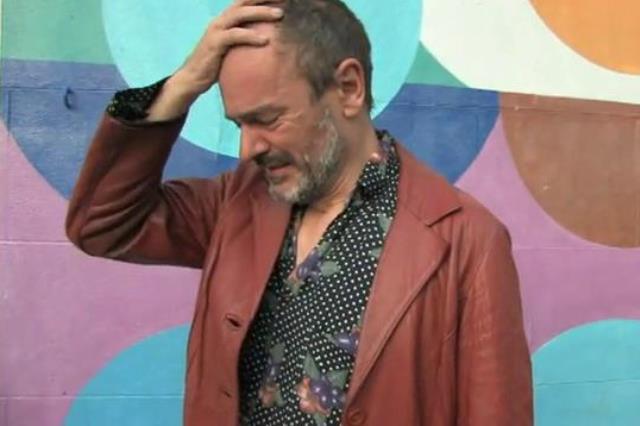

On screen, the gnomic Jones (pictured above left) comes across as frank but slippery. He did nothing about Headon’s departure. Jones, it seems, was a straw blowing in the wind. Strummer is seen in late-period archive clips unconvincingly waxing about punk. He looks like a lost man and was. The period saw the death of both of his parents. He was malleable. Vince White is an extraordinary presence (pictured below right). Gripping a can of beer in his interview segments and very self-aware, he swings between agitation and breaking down. Chimes, Howard and Sheppard are more measured. The latter-day Clash members concur that Rhodes was a nightmare and that Strummer was unmoored. Howard confesses to being baffled by the band's continued existence.

All this happened in the wake of recording Combat Rock (issued in May 1982), The Clash album which established them as a commercial force in America. They had ascended to being a stadium band. Instead of capitalising on the success, as is made all-too clear, Rhodes thrived on disruption so created and presided over a slow-motion car crash which, ultimately, resulted him making his very own Clash album.

All this happened in the wake of recording Combat Rock (issued in May 1982), The Clash album which established them as a commercial force in America. They had ascended to being a stadium band. Instead of capitalising on the success, as is made all-too clear, Rhodes thrived on disruption so created and presided over a slow-motion car crash which, ultimately, resulted him making his very own Clash album.

This is as fascinating to watch as the Metallica: Some Kind of Monster film. That, though, was made in real time, was a form of therapy and captured a healing process. For the downslide-times Clash, there was no mediation, no attempts to work out what was going wrong. All the while, Rhodes merrily kept hammering in the nails.

As a film, The Rise and Fall of The Clash suffers from the common rock-doc shortcomings: too many contributors to keep track of, a choppy structure, lack of flow, surface understanding and little appreciation of the outside world or context. Even so it is to be lauded as, by focussing on the bad times, it is a mould breaker. Watch and be mesmerised as this miserable tale unfolds.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment