Classical Music/Opera direct to home 7 - Jeremy Denk's well-tempered Bach revelations | reviews, news & interviews

Classical Music/Opera direct to home 7 - Jeremy Denk's well-tempered Bach revelations

Classical Music/Opera direct to home 7 - Jeremy Denk's well-tempered Bach revelations

The pianist shares his spoken observations and insights with natural charm and humility

One person playing one instrument from home to the edification and delight of thousands: it's been a constant in these confining days, and well meant even if the sound isn't always up to it, a necessary substitute for live communication on both sides. But this is something else: an education, a detailed sharing of love and consolation which makes me wonder why other musicians haven't taken up the challenge (maybe some have, but I haven't heard about it).

Bach has to have been central to all musicians in this time; if you have a blind spot, then that's a shame for you. In limbo here between a friend selling the Steinway Boudoir Grand that had been housed in too small a room for many years and taking delivery of another friend's upright which needs recondition, I've been frustrated by not doing what I long said I would – sit down and really work at Bach and Schubert. The next best thing has been to get to know the entire Well Tempered Clavier, all 48 Preludes and Fugues, on the five CDs from George Lepauw on the Orchid label (and much admired by Graham Rickson in his weekly classical CDs roundup). But that has been eclipsed both by the interpretation and the sheer range of human emotions discovered by Denk in master-lectures on five masterpieces in the series.

The 90 minute mix of talk and performance was originally scheduled this month for The Greene Space in New York, its aim "to change the world one person at a time...to share the mission of New York Public Radio to make the mind more curious, the heart more open and the spirit more joyful". This Bach adventure does all those things, though as Denk points out from his early 19th century Dutch barn in the Catskills, owls in a picture above and a piano which needs work but on which he nevertheless creates miracles, "happiness feels different, the things we feel grateful for are different" right now. For him, working on Bach without constraint has given him "a contentment I'm not used to having...an at-oneness with time" akin to yoga or meditation. His aim is to show us how Bach sustains the happiness "through light and dark", and his necessarily limited selection takes us into a central heart of darkness that still nourishes the soul before coming out into a playful, witty light.

The 90 minute mix of talk and performance was originally scheduled this month for The Greene Space in New York, its aim "to change the world one person at a time...to share the mission of New York Public Radio to make the mind more curious, the heart more open and the spirit more joyful". This Bach adventure does all those things, though as Denk points out from his early 19th century Dutch barn in the Catskills, owls in a picture above and a piano which needs work but on which he nevertheless creates miracles, "happiness feels different, the things we feel grateful for are different" right now. For him, working on Bach without constraint has given him "a contentment I'm not used to having...an at-oneness with time" akin to yoga or meditation. His aim is to show us how Bach sustains the happiness "through light and dark", and his necessarily limited selection takes us into a central heart of darkness that still nourishes the soul before coming out into a playful, witty light.

Starting with the C sharp major Prelude and Fugue, BWV 848 - we need the numbers because, of course, Bach takes us through the cycle of 24 keys twice, in two sets - he shows us what the left hand is doing as well as the right, how the energy hidden within the form is slowly unleashed in the form. He dislikes the word "subject" for the main fugue idea in each piece, especially when the C sharp major one is "balletic, kinetic", with a "gestural energy", a kind of a dance about a scale (the dancing is so evident in Denk's playing, and we return to it in his last two delectable choices). The first of the C minor Preludes and Fugues (BWV 847) he describes as "mad scientist" territory, taking dark matter and going off the rails, only to steer back to them: "we wouldn't love Bach so much if he didn't have his darker energy underneath". He refers to that animated cinematic masterpiece The Triplets of Bellegarde and how it uses the monomaniacal, almost machine-like Prelude for a bicycle race, because he thinks it's apt; he shows us how this Fugue, though in the minor, is playful in its energy and the chromatics accumulated. And he makes us realise throughout the genius of Bach's harmonic tricks, his deceptive cadences, before resolving each piece.

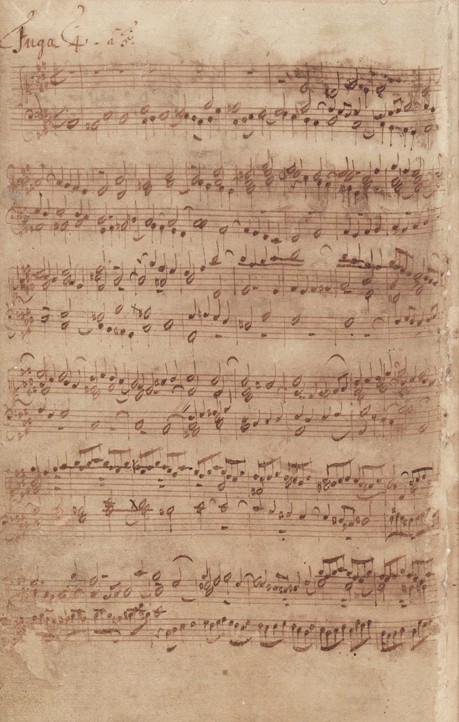

The BWV 849 C sharp minor Prelude and Fugue has, Denk says in especially thoughtful mode, a "tragic intensity" which he finds "a bit difficult to talk about right now", and he wants avoid being either glib or (over)-analytical; if ever a perfomer escaped those pitfalls, he's the one. It's almost as if he needs to clasp a coffee cup at times for comfort, putting it on the piano "which you should never do" before taking it up to keep the left hand from joining in with the right. We glide through the "endless melody" of the Prelude, its winding through "islands of major"; but it's the journey through the greatest of fugues which should be the immediate destination of anyone who doesn't have the patience to watch the whole.The "subject" is more an "idea to mull over" - just five notes, supposdly for the five wounds of Christ, in which if you remove any one note, all the mystery is gone in this "irreducible enigma" (opening page pictured above in Bach's manuscript). The countersubject, always necessary otherwise "you don't have a proper fugue", is soon shorn of all but its last few notes, and then there are scalic ideas which reach the most magical of cadences on E major, a much-needed "sense of solace". The miracle, a new idea of repeated notes, occurs one and a half pages in. It's almost trumpet-like, heralding something new, and the counterpoint becomes even richer in this "slow, circling, mythical" ritual: "three elements locked in a battle, trying to reinterpret each other, trying to find a mutual understanding".

The BWV 849 C sharp minor Prelude and Fugue has, Denk says in especially thoughtful mode, a "tragic intensity" which he finds "a bit difficult to talk about right now", and he wants avoid being either glib or (over)-analytical; if ever a perfomer escaped those pitfalls, he's the one. It's almost as if he needs to clasp a coffee cup at times for comfort, putting it on the piano "which you should never do" before taking it up to keep the left hand from joining in with the right. We glide through the "endless melody" of the Prelude, its winding through "islands of major"; but it's the journey through the greatest of fugues which should be the immediate destination of anyone who doesn't have the patience to watch the whole.The "subject" is more an "idea to mull over" - just five notes, supposdly for the five wounds of Christ, in which if you remove any one note, all the mystery is gone in this "irreducible enigma" (opening page pictured above in Bach's manuscript). The countersubject, always necessary otherwise "you don't have a proper fugue", is soon shorn of all but its last few notes, and then there are scalic ideas which reach the most magical of cadences on E major, a much-needed "sense of solace". The miracle, a new idea of repeated notes, occurs one and a half pages in. It's almost trumpet-like, heralding something new, and the counterpoint becomes even richer in this "slow, circling, mythical" ritual: "three elements locked in a battle, trying to reinterpret each other, trying to find a mutual understanding".

I see I've become like the student trying to regurgitate the master – but watch, and you'll see how it comes to life in tandem with the constant playing (Denk rarely needs to look at his hands as he talks). With the BWV 850 D major and BWV 858 F sharp major Preludes and Fugues, introduced together and then played, so vivaciously, together as a finale, we come out into light and play, finding how diminished-seventh delays can be part of the humour, how a different kind of energy comes from a different kind of fugue subject. Denk calls the F sharp major his "sentimental favourite" and lives the fun in the hockets or out-of-step mirrorings of left and right hands in the Prelude, the seasoning added to the dish of the Fugue. If anyone ever doubted that Bach could be witty, here are your answers.

Of course it leaves you wanting even more: I was hoping Denk would take us through the A minor Prelude, BWV 889 with its amazing way-before-Schoenberg rows of all twelve notes of the chromatic scale, but it seems his scope is limited to Book One (update: I understand a second instalment is due on 28 April - more details anon). We'll just have to plead for 20 minute films on each of the Preludes and Fugues, however long it takes the pianist to get round to them (and as he says, even a short and seemingly simple pair can give each day a "refreshing sort of recreation" – there's plenty of time to change and develop one's thoughts about these supreme masterpieces). Meanwhile, if you loved that, you'll enjoy the below, too – firt in a series of thoughts on some of the Goldberg Variations, which he's also recorded (the film below is on the Aria). I have a feeling that if Denk also brings out four of five discs devoted to The Well Tempered Clavier, they might displace the ones I already listen to the most.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Add comment