Album: Steve Earle & The Dukes - Ghosts of West Virginia | reviews, news & interviews

Album: Steve Earle & The Dukes - Ghosts of West Virginia

Album: Steve Earle & The Dukes - Ghosts of West Virginia

Steve Earle digs deep for an album of pitch-perfect Americana

Guy Clark, Steve Earle’s mentor and champion and the singer-songwriter to whom he paid homage on his 2019 album, once said that “songs aren’t finished until you play them for people”. By which he surely meant live, creating that vibe for which the best system, or headphones, is no substitute.

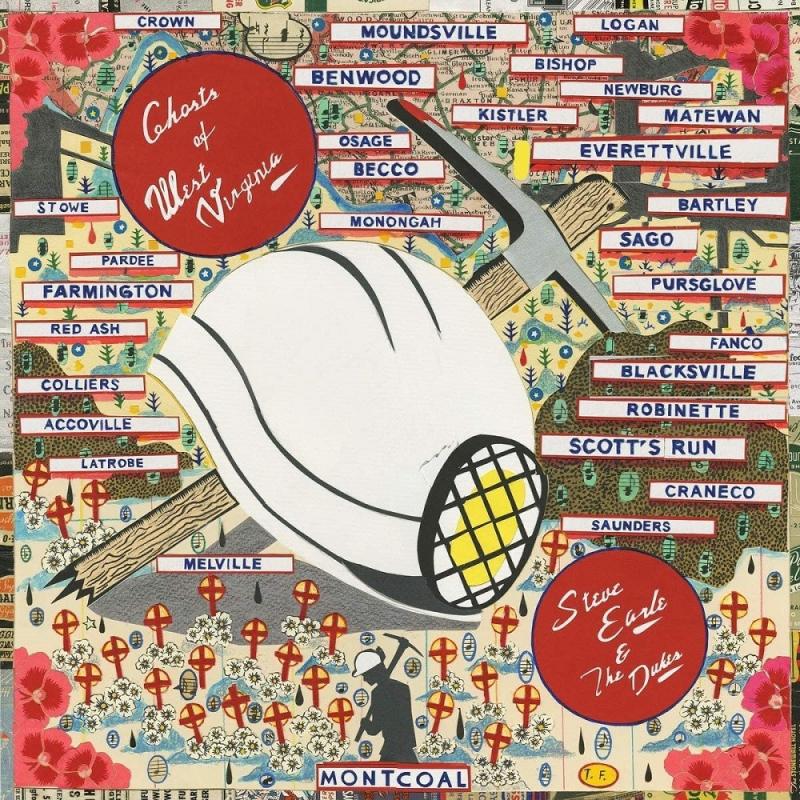

Ghosts of West Virginia is Earle’s 17th studio album and it was recorded with The Dukes in the fabled Electric Lady Studios in Greenwich Village, a stroll across Washington Square from where he’s lived these past 15 years and which he celebrated with Washington Square Serenade (2007), an album destined eventually for the stage. And Earle was on stage when life was so rudely and catastrophically interrupted, playing at New York’s Public Theatre in Coal Country by Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen, a docudrama which had only just opened.

Earle’s songs, which he performed from a chair, playing guitar and banjo, are a commentary on the story and the community among which it is set, a real-life West Virginia community ripped apart a decade ago by the Upper Big Branch mine disaster which took 29 good men – each is named in the chilling “It’s About Blood”. It was the third Appalachian mining disaster in four years. Neither the play nor Earle’s songs pass judgment on the rights and wrongs of mining. Rather they bring together the testimonies, the memories, and the grief of those left behind (pictured below by Jacob Blickenstaff, Steve Earle and The Dukes at Electric Lady Studios).

Ghosts of West Virginia is a powerful suite of songs at once both new and familiar-seeming, for they draw on folk music tropes (the call and response of the opening track, “Heaven Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere”, for example, a song with echoes of Earle’s “Jericho Road”) and feature a West Virginia folk hero, pile-driving man John Henry, after whom Earle’s youngest son is named. Seven of the songs are from the play, the additional three “are not directly related to the events” of that fateful day but they are all “dedicated to the people of West Virginia who occupy a unique position in the history of the United States of America.” It’s one of the country’s poorest, dependent on coal and lumber, where folks “take whatever fate provides”, as he sings on the tender and reflective “Time Is Never On our Side”.

Ghosts of West Virginia is a powerful suite of songs at once both new and familiar-seeming, for they draw on folk music tropes (the call and response of the opening track, “Heaven Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere”, for example, a song with echoes of Earle’s “Jericho Road”) and feature a West Virginia folk hero, pile-driving man John Henry, after whom Earle’s youngest son is named. Seven of the songs are from the play, the additional three “are not directly related to the events” of that fateful day but they are all “dedicated to the people of West Virginia who occupy a unique position in the history of the United States of America.” It’s one of the country’s poorest, dependent on coal and lumber, where folks “take whatever fate provides”, as he sings on the tender and reflective “Time Is Never On our Side”.

The songs reflect the lived reality of those in its mining towns and Earle, whose distinctive voice roils up from the depths, tells their stories well. The a cappella of “Heaven Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere”, its lyrics mixing bar and Bible in that way that southerners always do, gives way to a rolling country song, “Union, God and Country”, which sums up the poor workers’ lot. “Devil Put the Coal in the Ground”, Earle’s banjo to the fore, Eleanor Whitmore’s fiddle gracefully intertwining, is a powerful two-step, driven by Brad Pemberton’s percussion and Jeff Hill’s bass. Ricky Jay Jackson’s dobro adds that distinctive “dirty” sound.

The album’s pacing is perfect: “If I Could See Your Face Again”, sung by Whitmore in a heartrending performance of which Emmylou Harris would be proud, is sequenced between “It’s About Blood” and the visceral “Black Lung”, which in turn gives way to a rockabilly celebration of flying ace Charles Elwood Yeager, which takes us into “The Mine”, a country ballad. “It’s gonna get better when my brother gets me on at the mine,” Earle sings in the gravelly voice of weary resignation that’s so expressive of the miner’s lot.

Ghosts of West Virginia is Americana at its finest, and the Dukes – husband-and-wife team Chris Masterson and Whitmore, Jackson, Hill, and Pemberton – are tight and cohesive. Earle himself produced and the album is recorded in mono, a response to Earle’s hearing loss which means he can no longer discern stereo separation, but which feels entirely appropriate to the subject matter.

The album is dedicated Charles Kelley Looney, Dukes’ bassist, who died suddenly last year. And let’s hope the play gets its moment in the post-Covid sunlight.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Add comment