theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Mike Hodges | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Mike Hodges

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Mike Hodges

The British writer-director reflects on the making and meaning of his thriller 'Black Rainbow'

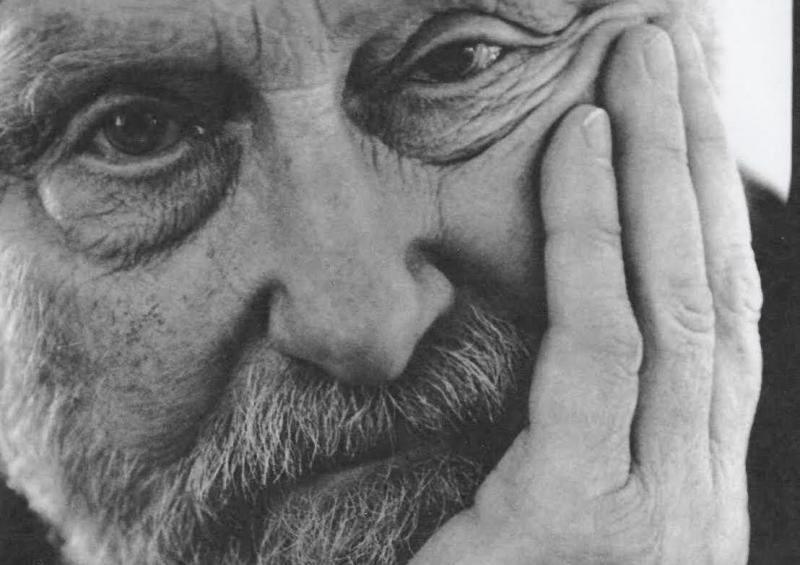

It can be reasonably argued that Mike Hodges, who died on 17 December, was the finest director of British crime films since Alfred Hitchcock.

Mike Hodges arrived in cinema through television, including a stint on the rightly revered Granada Television current affairs series World in Action. He burst on to the big screen in 1971 with the gritty and witty crime thriller Get Carter, which revealed both his brilliant eye and piercing lack of sentiment.

Since then, Hodges has had a career of highs and some lows, but he has always been a thorough professional, willing to tackle such extremes as the absurd fantasy of Flash Gordon (1980) or the intelligent introspection of Croupier (1989), which enjoyed great success in the USA.

Hodges's Black Rainbow (1989), which he directed from his original screenplay, was a victim of distribution failure and has been too little seen. It’s set in North Carolina, where a tortured medium, Martha Travis (Rosanna Arquette), and her alcoholic father Walter (Jason Robards Jr) are touring their act. When Martha’s questionable abilities to speak to the other side extend to predictions of violent deaths caused by slack industrial safety measures, she is pursued by both a journalist, Gary Wallace (Tom Hulce), and a slimy hitman.

A compelling melange of Southern Gothic, political thriller, and the supernatural, Black Rainbow has grown quietly in stature over the decades, and its release on Blu-ray next week should finally win it a wider audience. In 2020, Hodges was about to enjoy a full retrospective at BFI Southbank in London and the release of a biographical documentary, All At Sea, but then the pandemic struck. He spoke to me from deepest Dorset where he has resided for some years. On the eve of his 88th birthday, he remains as sharp as his movies.

DAVID THOMPSON: Black Rainbow was made at the end of the ‘80s – 30 years ago. How does it look to you now?

MIKE HODGES: “We don’t understand what we’re doing," says Martha when describing the horrors of our self-destructive behaviour. Her dubious talent as an itinerant medium for communicating with departed "loved ones" has mysteriously been replaced by witnessing deaths before they happen. Right now, you and I are talking in the middle of a lethal pandemic that’s ripped the lid off society, revealing much of what Martha’s predicting: a black hole of poverty, inequality, avarice and, worst of all, the callous exploitation of most of the planet’s population.

When the journalist Gary Wallace finally tracks her down after she disappeared a decade earlier, he’s shocked: “Your eyes, Martha. They look like they’ve seen too much". TS Eliot’s words seem appropriate here: “Humankind cannot bear very much reality". Ironic that it’s taken an invisible enemy, the virus, for us to finally see the always visible one. I wrote the script over 30 years ago, but even then it was pretty obvious the globalised edifice we were building would prove dangerously unstable.

How do you place the film in your career?

Difficult to say. Despite good reviews it was abandoned by its UK and US distributors. Unbeknown to Goldcrest, which was the production company, both Palace Pictures and Miramax were in financial difficulties at the time. One quickly dumped it into the VHS market, the other onto a cable channel. Even so, it did win Best Film and Best Actress awards at the Sitges and Porto film festivals. Many years ago, I remember meeting a director whose last film had tanked at the box office. He cheerfully told me it was big in Malta. Malta? Well, I can do slightly better than that. I was told by a Japanese musician who works with composer Simon Fisher Turner [who scored Hodges’s Croupier and the 2003 I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead] that Black Rainbow was big in Japan. He’d seen it six times – in a cinema! Hopefully, with it coming out on Blu-ray, it’ll finally have a full life. (Pictured below: Rosanna Arquette)

Much of Black Rainbow was clearly born out of your experience of North America. What were your first impressions of American life and culture, and what subjects did you cover in your TV years there?

Much of Black Rainbow was clearly born out of your experience of North America. What were your first impressions of American life and culture, and what subjects did you cover in your TV years there?

In 1964, I was sent by World in Action – Granada’s investigative programme – to Dallas to film a profile of right-wing Senator Barry Goldwater. He was the Republican Presidential Candidate who wanted to nuke North Vietnam. Also in Dallas, I caught up with the racist Governor George Wallace. Then I went on to Detroit to interview the left-wing Reuther brothers [Walter and Victor] of the United Automobile Workers – both shot and wounded in their own homes by G-men employed by the manufacturers. Then later that same year, I covered the war in Vietnam. That’s one hell of an introduction to America. I was to sample first hand its obsession with and genuine fear of communism. For many Americans, our National Health Service and the BBC were commie institutions.

Even before Reagan – and Thatcher in the UK – America’s extreme form of capitalism was ruthless, disturbingly so. And there was no escaping it. To my European eyes, every inch of the country seemed covered in advertising. Every radio and television station was endlessly streaming vacuous commercials. It seeped into every space – taxis, elevators, foyers, shops.

Later, when I was previewing Flash Gordon and location-hunting for Omen II [from which Hodges was unceremoniously fired], I became fascinated by the local newspapers with vivid names like Bugle, Bee, Sentinel, Patriot. They gave me an insight into the lives of ordinary citizens away from the big cities. One story that kept surfacing was the beating up or even murdering of factory workers, usually foremen or union officials. On investigation, it was almost always for whistleblowing on breaches of health and safety regulations. It wasn’t long after Black Rainbow was made that a fire broke out in a chicken processing factory [in Hamlet, North Carolina, on 3 September, 1991]. It was right next door to a location I’d used. Twenty-five people lost their lives. The doors were locked and they couldn’t escape. That shook me. A similar accident happens in the film. Reality was echoing fiction.

What had made you choose North Carolina, and particularly Charlotte, as the setting for the film?

Some years earlier, I’d made an HBO film called Florida Straits [1986], starring Raúl Juliá and Fred Ward. The script wasn’t great but it was going to be shot in Mexico, a country I love, so I signed up. Much of the film’s action took place in the Cuban jungle so the right location was imperative. For reasons too ludicrous to relate, the producers decided against Mexico and instead chose Shelby, North Carolina, a small town not unlike Peyton Place. You didn’t have to be Albert Einstein to realise this production was going to be a nightmare. And it was.

Indeed, the only good thing about it was my first sighting of Charlotte. It was a city on the cusp, much like Newcastle was when I filmed Get Carter. In the centre was a brand new citadel – I was told computers liked the climate there – which was encircled by decay and poverty. It reminded me of Edward Hopper’s paintings. Visually, I was immediately attracted to it, and I was also to the fact that it was set in the Bible Belt. (Pictured below: Hodges, behind the camera, directs Michael Caine and Ian Hendry in Get Carter)

I was brought up as a Roman Catholic and, despite abandoning it in my teens, I’ve always been curious about religious beliefs, particularly in America. Over many years, I’d been following the antics of evangelical preachers like Jimmy Swaggart and Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker. I was fascinated at the way these preachers extracted huge sums of money from the poor and displaced. Even when they were found wanting – Swaggart had a predilection for prostitutes! – their followers stuck with them. No scandal, however unseemly, could dent their reputation with their followers. As it is with Donald Trump.

Martha, the central character in Black Rainbow, is a medium, and you leave it open whether she is authentic or fraudulent. I watched on YouTube some footage of the famous British medium Doris Stokes in action, at the Barbican! Many details – such as a fan blowing and her banter with the audience – recur in Martha’s act. How much was Stokes an inspiration for Martha, and did you do further research?

Martha, the central character in Black Rainbow, is a medium, and you leave it open whether she is authentic or fraudulent. I watched on YouTube some footage of the famous British medium Doris Stokes in action, at the Barbican! Many details – such as a fan blowing and her banter with the audience – recur in Martha’s act. How much was Stokes an inspiration for Martha, and did you do further research?

Doris Stokes was the sole source for my characterisation of Martha and her act. She probed the audience for facts on which she would build her connection with the departed, or discard a lead [for being unfruitful] when necessary. Martha’s father Walter admonishes her the first time she slips into a time warp and predicts a death before it’s happened: “How many times have I told you? When you’re following a wrong one, let go.”

Whenever I feel the need for some back story, I try to knead it naturally into the film’s fabric. In this scene, via Walter, I had the opportunity to do just that. We learn that Martha’s been on the road since childhood, that she’s been trained by Walter and possibly her mother, and that there’s no way she can get off the treadmill. “Only a few more years," says Walter, “before we can retire to the land of milk and honey."

Walter reminds her that her mother insisted she, Martha, had appeared to her while they were hundreds of miles apart. Bi-location is the word used to describe this phenomenon. Padre Pio [the Italian stigmatist] is its best known example. This reference by Walter is a clue to what happens much later when Martha “appears” simultaneously to Walter and the assassin. Or is it that Martha’s image has already taken possession of their minds – Walter’s through guilt, the killer’s through revenge? The mind can play terrible tricks. Some devout Christians unwillingly replicate Christ’s wounds by simply contemplating his crucifixion. Stigmata is a religious trick. But if you want to explore something more scientific, try Quantum Theory. Particles in two places at the same time? The Uncertainty Principle? Entanglements?

You conceived, wrote, and directed Black Rainbow. How would you contrast this experience with making adaptations or taking on projects written by others?

Obviously, if it’s your original script the choice of subject will be one you’re passionate about. Then, as the story unfolds in the process of filming, you’re also free to change it at will. You don’t have to consult the screenwriter – you are the screenwriter. I found adapting novels tricky. With both Ted Lewis [author of Jack’s Return Home, the source of Get Carter] and Michael Crichton [author of The Terminal Man, which Hodges adapted for his 1974 film version], I initially felt obliged to respect the text. In the end, however, I found it necessary to change both stories in pretty radical ways. But it wasn’t something I found easy.

You’re a published novelist yourself, and I’m wondering what models you might have as a writer. Much of the dialogue in your films has the flavour of certain hard-boiled American fiction writers. Black Rainbow may be set in the 1970s, but it feels like it could be decades earlier.

I’ve always been a fan of hard-boiled American fiction writers – Nathanael West, Flannery O’Connor, Raymond Chandler. I’m not sure if you’re right about my dialogue in this script. That said, if you’re going to be influenced, make sure your sources are the very best. When it comes to original screenplays as opposed to novels, then Billy Wilder and his collaborators are at the top of my list. You’re right – the film feels like it’s taking place decades earlier.

It’s the same with Get Carter, which is set in the late ‘60s but could be taking place any time from the ‘40s onwards. I think it’s mainly because both Newcastle and Charlotte are cities in transition between a static and a dynamic world of the future. It’s this that appeals to me. When Walter in Black Rainbow notices the developers have finally hit town, Eunice [Mary Ratliff], the black lady driving him and Martha, retorts: “They’re tearing our hearts out". “Worse,” says Walter. ”They’re gobbling up your past like a plague of locusts. It’s a lobotomy. A national lobotomy." I confess to liking the timeless quality of both films. (Pictured below: Robards, Arquette, and Ratliff)

In the commentary you recorded for the Black Rainbow Blu-ray, you speak about the film as being the first in which you sought to simplify your style. Can you say why and how this has changed your way of making films?

In the commentary you recorded for the Black Rainbow Blu-ray, you speak about the film as being the first in which you sought to simplify your style. Can you say why and how this has changed your way of making films?

Don’t know why I said that. From the start of my career, I’ve tried to simplify my style. By that I mean compressing scenes into a single shot where possible. The tension of playing them in one continuous take is great for the actors. And great for editors. I have a loathing of films where scenes are cut together like a tennis match at Wimbledon: wide shot, close-up, close-up, close-up, wide shot, and so on.

This was the first film shot for you by Gerry Fisher. Why did you choose him as the cinematographer and how did you work together?

John Huston was a great, if erratic, director. I particularly admired the simplicity of his later low-budget films – Fat City and The Dead. But it was Wise Blood I always went back to. Set in the Bible Belt, it covers the same evangelistic territory as Black Rainbow. Gerry Fisher was Huston’s director of photography on Wise Blood and the obvious choice. Gerry had an intuitive talent for finding the simplest way to light a scene. And the result was almost magical. Fast and simple. What more can a director ask?

The palette of the film is predominantly brown with some green. Why did you choose those colours?

It certainly wasn’t an intentional decision. I don’t remember talking to Gerry or Voytek, my production designer, about any colour scheme. Maybe it’s the accidental influence of Edward Hopper?

You’ve said in interviews that you had trouble finding an actress to play Martha. Why was that – and what special qualities do you think Rosanna Arquette brought to the role?

I’ve had this problem before. Decades before, I wrote a screenplay called Say Goodnight Lillian – Goodnight. The protagonist is the wife of a commodity broker in Chicago. Their marriage has dried up and she’s bored. We find that she has a secret apartment where every evening she changes her sedate middle-class clothes for an overtly sexy outfit. You think she’s a hooker, as in [Luis Buñuel's] Belle de Jour. But you’re wrong. She’s a comedian working between the acts in a strip joint and her patter is about her husband. She’s like Joan Rivers. It’s a way of exorcising her frustration. All’s well until a local journalist finds out her real identity. When this hits the headlines, the husband becomes a laughing stock. The result? He becomes a recluse while she becomes a television star appearing on all the talk shows. It was a terrific role but no actress wanted to play it. As her fame grew so her comedy material changed from the marital to the political. I suspect it was this that put actresses off – she was questioning rampant materialism and the way we were destroying the environment.

Similarly with Black Rainbow. Again, I think it was Martha’s questioning of religious belief, life after death, even the existence of God that put them off. I’ll always be grateful to Rosanna for having the courage to take the role on. It was interesting to see the affect she had on the audiences. Many of them were emotionally affected by her act. Some were even crying. Her apparent sincerity and simplicity created the exact atmosphere I’d hoped for.

How far were Jason Robards Jr and Tom Hulce the kind of actors you were looking for in the other principal roles?

Burt Lancaster was very interested in playing Walter but eventually declined. I’m glad. There would have been the inevitable comparison with Elmer Gantry, but more importantly he would have been too strong for the role. Jason, with all those Eugene O’Neill Broadway productions behind him, was a perfect shoo-in. Hearing him deliver the lines I’d written was one of the greatest delights of my career. He made them zing. “You heard what the woman said – her husband's at home watching television. In some households that’s considered being alive." I was also lucky with Tom. The rest of the cast were all locals. The Jewish police chief was – believe it or not – a dentist. But I must mention the extras at Martha’s shows. They were extraordinary – attentive and totally believable. That was thanks to Rosanna. (Pictured below: Tom Hulce)

What kind of score did you ask John Scott to give you? I recall seeing an early cut of the film in which you had used Varèse’s “Amériques”, which John seems to have followed!

What kind of score did you ask John Scott to give you? I recall seeing an early cut of the film in which you had used Varèse’s “Amériques”, which John seems to have followed!

The danger of putting music into the rough cut is that the poor composer is almost compelled to copy it. The same thing happened on Squaring the Circle [1984], Tom Stoppard’s television film [directed by Hodges] about Solidarity and the Polish uprising. When the police violently break up Solidarity’s office, I put Varèse’s “Amériques” over it. The composer, Roy Budd on that occasion, did much the same as John. In fairness, it’s a very compelling composition, difficult to shake off it seems. John brought me a wonderful score. He also scored A Prayer for the Dying [1987] brilliantly for me. Sadly, in the dismal process of re-editing the film without my consent, the Goldwyn Corporation replaced it.

Black Rainbow is usually described as a “supernatural thriller”. I notice those who criticise the film tend to say it tries to be too many things and doesn’t stick to any particular genre. What are your thoughts on this?

The main criticism is the very last shot when Gary Wallace returns to the shack where he finally found Martha. In truth, I added this at the very last minute – and was tempted to have Gary’s voice-over repeating Martha’s line to Walter: “You stole my life.” And in a way she had. Gary had been obsessed with her for over a decade. The film played at the Santa Barbara Film Festival the year I made it. Afterwards two producers complained I hadn’t frightened the audience enough. I hadn’t had them biting their fingernails, sitting on the edge of their seats. In short, they had totally misread it. It wasn’t that kind of film and I’m not that kind of filmmaker. I’m more interested in atmosphere. I’m quite happy to let the story unfold at its own pace, allowing the audience time to absorb what they’re witnessing. Of course, if reports of the prevailing attention span deficit are true, this is a dangerous tack to be on. But then my career’s over, so it no longer matters.

Mike Hodges, 29 July 1932 – 17 December 2022

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Add comment