Eavesdropping on Rattle, the LSO and Bartók’s Bluebeard | reviews, news & interviews

Eavesdropping on Rattle, the LSO and Bartók’s Bluebeard

Eavesdropping on Rattle, the LSO and Bartók’s Bluebeard

Ahead of the London Symphony Orchestra’s streaming next month, a privileged preview

One source of advance information told us to expect a reduced version of Bartók’s one-act Bluebeard’s Castle, among the 20th century’s most original and profound operatic masterpieces.

Coincidentally a famous Bluebeard, bass John Tomlinson, guested that same afternoon to talk about Wagner's Wotan/Wanderer on my Zoom Siegfried course, and when I mentioned that I was shortly heading up to Old Street, he sang a snatch of Bartok's Hungarian setting and commented "oh yes, that's one of Simon's favourite pieces". It's easy to understand why. Famously, the opening of the fifth castle door when new wife Judith turns the key reluctantly granted by her sombre spouse Bluebeard has often been cited as a “tingle quotient” moment: a blaze of C major for full orchestra and organ as the blinding splendour of Bluebeard’s kingdom reveals itself. It’s indebted to the sunrise opening of Richard Strauss’s Also sprach Zarathustra (think Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey), the work which made the young Bartok determined to pursue a career as a composer in 1902, nine years before he penned the opera.

The twist is that Judith, shrivelled by the glory though not incinerated like Semele in the presence of Zeus/Jupiter’s godhead, can only squeeze out a wan response, unaccompanied, in an alien key. It's the kind of thing that makes Bartók’s take utterly original, like so much else in the score. Of course there is no organ in the converted Hawksmoor church now - an electronic keyboard had to serve - but nor is there in the Barbican where the performance would have taken place had the pandemic crisis not happened. Imagine our amazement at the sound, six months on from anything like it.  St Luke’s acoustic can verge on the dry, but the LSO’s superlative warmth carried the evening: those silky, aching violins, the prominent Magyar twists of the many crucial clarinet solos, the luminous-eerie first horn. And though Cargill (pictured above) and Finley (pictured below) were at the furthest point in the venue from the centrally-seated spectators, and could be overpowered by the orchestra from that perspective in a way that they won’t be in the film, no-one unfamiliar with the work would have been in any doubt of the dramatic dynamic: troubled man so wanting to reach out but trapped in his own misery, curious woman pushing to know more about her husband, to the point of violence and hysteria before the last, devastating reveal of the seventh door.

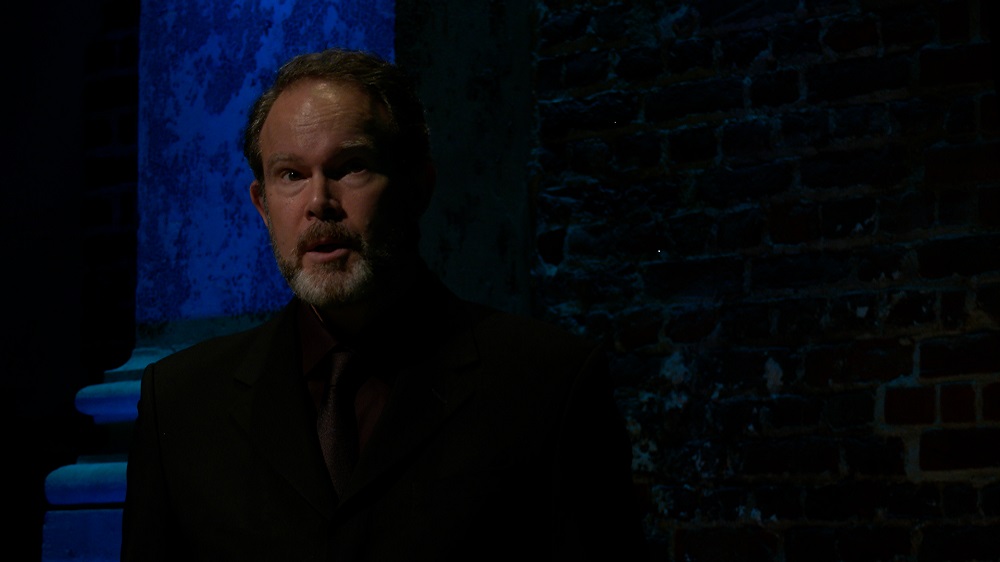

St Luke’s acoustic can verge on the dry, but the LSO’s superlative warmth carried the evening: those silky, aching violins, the prominent Magyar twists of the many crucial clarinet solos, the luminous-eerie first horn. And though Cargill (pictured above) and Finley (pictured below) were at the furthest point in the venue from the centrally-seated spectators, and could be overpowered by the orchestra from that perspective in a way that they won’t be in the film, no-one unfamiliar with the work would have been in any doubt of the dramatic dynamic: troubled man so wanting to reach out but trapped in his own misery, curious woman pushing to know more about her husband, to the point of violence and hysteria before the last, devastating reveal of the seventh door.

Cargill isn’t just a British/Scottish great, she’s one of the world’s most impressive artists, fully inhabiting everything she sings with a wealth of colour in every part of the stunning mezzo voice. Finley’s equally splendid bass-baritone managed to win the sympathy you think you’re never going to feel for this lost soul before irredeemable darkness falls. It’s often said that a concert performance with sufficiently sensitive lighting can leave the imagination more room to manoeuvre than an over-specific production. A couple of video projections, the ubiquitous door and appropriate lighting changes in a superb setting with the original pilasters doubling as castle architecture – Hawksmoor would lugubriously approve – as well as a few moves, not least Cargill’s up a spiral staircase for high noon, did the trick. I have no doubt it will work on screen, if you have one big enough, and a good sound system. And don’t forget that, Covid-19 rules still permitting, you can be back in the Barbican for Rattle conducting Stravinsky and Beethoven – the five piano concertos with Krystian Zimerman, no less – from the end of November. The LSO is one orchestra which has played its cards, and its funding, right so far; may the other London teams be able to follow suit soonest.

It’s often said that a concert performance with sufficiently sensitive lighting can leave the imagination more room to manoeuvre than an over-specific production. A couple of video projections, the ubiquitous door and appropriate lighting changes in a superb setting with the original pilasters doubling as castle architecture – Hawksmoor would lugubriously approve – as well as a few moves, not least Cargill’s up a spiral staircase for high noon, did the trick. I have no doubt it will work on screen, if you have one big enough, and a good sound system. And don’t forget that, Covid-19 rules still permitting, you can be back in the Barbican for Rattle conducting Stravinsky and Beethoven – the five piano concertos with Krystian Zimerman, no less – from the end of November. The LSO is one orchestra which has played its cards, and its funding, right so far; may the other London teams be able to follow suit soonest.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Add comment