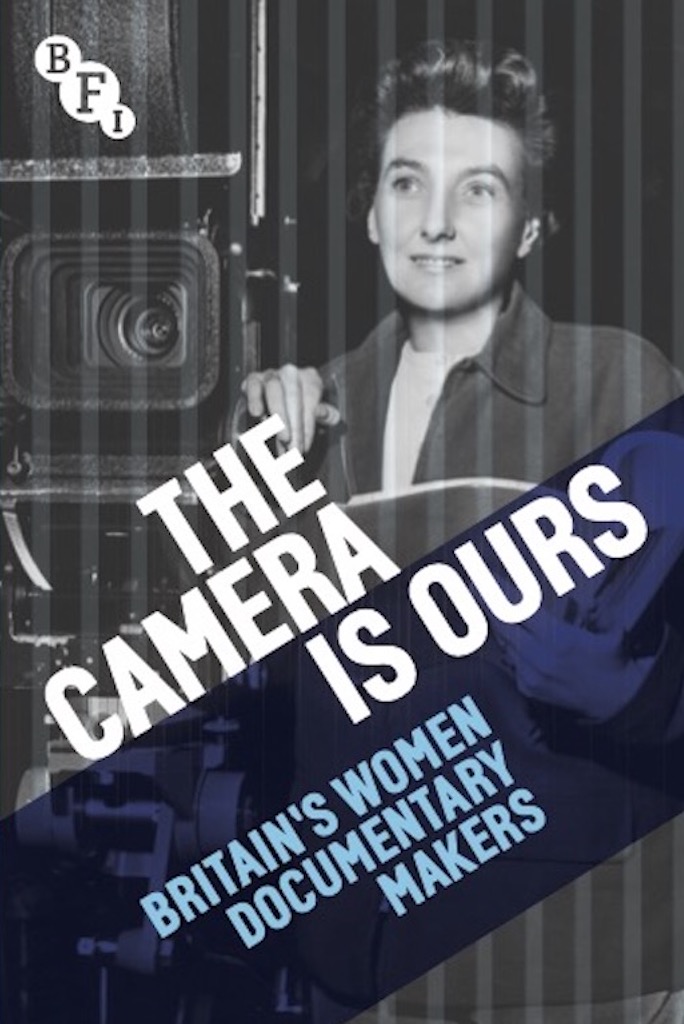

The Camera Is Ours features films made from 1935-1967 by women like Marion and Ruby Grierson, Evelyn Spice and Margaret Thomson, whose names should be engraved in the history of British film-making.

Ever heard of them? Probably not as, surprise, surprise, they’ve been overlooked – until now, that is. This BFI two-disc DVD release includes 10 newly restored shorts along with interviews with Sarah Erulkar and Kay Manders and a feature on Jill Craigie, better known as the wife of labour leader, Michael Foot.

“We were a movement,” Manders tells Barney Snow. “We had ideas in common. We thought we were going to change the world; everything in the future was going to get better.” And a key element of that belief was to give other women a voice.

In a drive to attract women voters, in 1945 the Labour Party commissioned her to make Homes for the People, a film designed to highlight the need for better housing. Housewives from places as varied as a London estate, a Welsh mining village and Moreton Pinkney in Northamptonshire describe what it’s like to drag a heavy pram up six flights of stairs, wash off coal dust in a tin bath in the living room or use a bucket as a lavatory.

In a drive to attract women voters, in 1945 the Labour Party commissioned her to make Homes for the People, a film designed to highlight the need for better housing. Housewives from places as varied as a London estate, a Welsh mining village and Moreton Pinkney in Northamptonshire describe what it’s like to drag a heavy pram up six flights of stairs, wash off coal dust in a tin bath in the living room or use a bucket as a lavatory.

Especially radical is the way Manders describes housework as a job. “Those whose job is running the home must have conditions as good as the man in the factory and all the equipment she needs,” says the voice-over. “Houses must be planned to meet family needs. Everyone must insist; our voice must be heard through all the channels open to us… We must elect to parliament those whose interest is the welfare of the working people of the country.” Manders is the first to acknowledge that, according to the way the term is used today, campaigning shorts like this are not documentaries.

In effect, Margaret Thomson’s The Troubled Mind, from 1954, is a mini-feature with Adrienne Corri (who later appeared in A Clockwork Orange) playing a trainee nurse. Shot in Shenley Hospital, a progressive psychiatric hospital, the film was part of a Ministry of Health drive to recruit mental health nurses. Corri is shown round by a staff nurse. As we watch patients dancing, gardening and basket weaving, she exclaims, “We do have a pretty gay time!”

Not surprisingly, the shuddering horrors of ECT (electroconvulsive therapy) are shown only through Corri’s reactions to them. “No actual patients played any part in this film,” we are told as the credits roll, which made me laugh out loud since those playing the inmates exploit every cliché in the book concerning “crazy” behaviour.

John Grierson has been dubbed the father of British documentary film, yet his sisters Ruby and Marion made similarly important contributions. In They Also Serve, commissioned in 1940 by the Ministry of Information, Ruby pays tribute to the crucial role played by housewives during the war. We see a woman going through her daily routine of domestic chores, while her thoughts are aired in voice-over.

To realise how rare it was for women to be invited to speak, you only have to watch Budge Cooper’s Birth-Day. Commissioned in 1945 by Scotland’s Department of Health, it was designed to encourage pregnant women to access maternity care as soon as possible. The expectant mother is played by Molly Weir (of Rentaghost), as a timid creature patronised by all and sundry. Her soldier husband begs for leave to be with her; cue for his commanding officer to give him a lecture on pregnancy and childbirth and itemise the services available for his wife.

The absurdity of an army officer mansplaining childbirth provides a glimpse of how deeply patronising society was at the time. Racism, classism and sexism are revealed in many a voice-over spoken in clipped RP by God-like men. Not long after Birth-Day, Cooper abandoned film-making, only to take it up again in 1957, when she began making safety and first aid films for the National Coal Board. She had to take the NCB to court, though, before they would let her go down the pits.

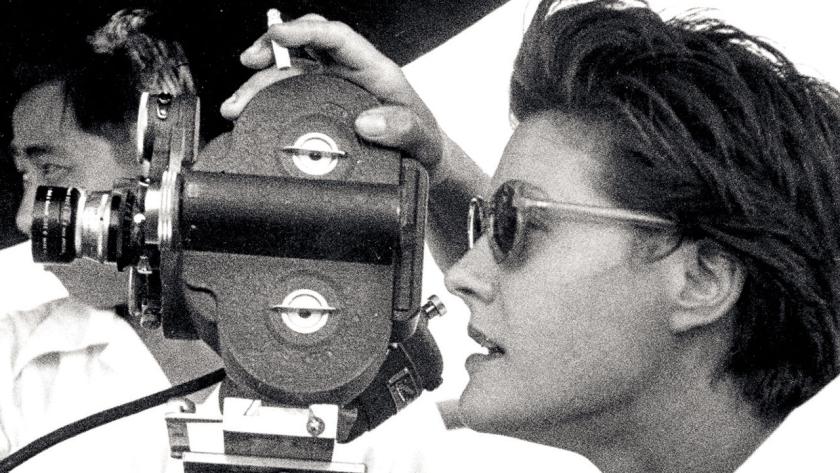

Lizzie Thynne’s lively, feature-length biopic of Jill Craigie brings home the obstacles thwarting the ambitions of women hoping to carry on directing after the war was over. Clips from extant interviews with Craigie are intercut with footage of Hayley Atwell playing her as a young woman. “You may wonder why you haven’t heard of me,” says Craigie. Out of Chaos, her film about war artists like Henry Moore and Stanley Spencer, was described in the Daily Telegraph as “one of the best and most entertaining films ever made in this country” yet, she says, she was still regarded as “an absolute freak… A woman in charge of 40 men; who’d believe it?”

Out of Chaos was produced by the Rank Organisation, whom she persuaded to fund The Way We Live, a feature about the post-war redevelopment of Plymouth. Demanding “What is that bitch up to?” the local Tory MP, Lady Astor, tried to get the film stopped for being too socialist. Not only did it get made, though, but in the city it broke box-office records.

Documenting demands for equal pay, To Be a Woman, from 1950, was the last of Craigie’s post-war films. She began writing scripts for features like The Million Pound Note (1954) and Windom's Way (1957) before trying, without success, to break into television. Having married Michael Foot in 1949, she gradually began devoting more time to political work; she was a founder member of CND, for instance. In 1995, though, she returned to film making with Two Hours from London, documenting Serbian atrocities in Bosnia and Croatia (it was narrated by Foot). At the age of 83, she found her director’s voice once more.

The Camera Is Ours is a must for the archives, but sadly it’s hard to imagine many besides cinema buffs watching educational and recruitment shorts. Thynne’s Independent Miss Craigie is a delight, on the other hand. And once you learn about the obstacles put in the way of talented directors like her, it makes you want to pay homage to the others – even if it means watching public information films.

Add comment