Two boys in east London, one Black, one white, grow up together, play pranks at school, then decades later have a tempestuous falling out. That’s the main narrative arc of these twin plays, but it accounts for none of their extraordinary richness and the superlative acting they entail.

These are monologues, a genre where dramatic excellence is primed to go right off the scale: think the powerful solos of Brian Friel’s Faith Healer, the haunted storytellers of Conor McPherson’s plays, Simon Stephens’s Sea Wall. Recast after their runs at the Dorfman, the trio of plays is directed by Clint Dyer, who also cowrote the texts with Roy Williams. (The third in the cycle, a two-hander titled Closing Time, previews from August 21.) It’s a form of drama perfectly suited to Soho Place’s intimate playing area: narration that verges on performance art, with a hefty dash of stand-up comedy (including the audience participation kind, but fear not, it’s a joyous experience).

Language here comes at you in a welter, thick and fast, almost too fast to process at times, as the two men relive their memories, cast around for answers and spill out their secrets. It’s brilliant writing, demotic and urgent, showing two different tribal languages at work that spar not with each other but with the formal discourse of “the powers” that they perceive run things and close down their hopes. Black Delroy, so confident in himself, wilts and stutters under the pressure of addressing a court without his knee-jerk casual swearing and feels obliged to translate his bursts of patois to the worthies there. And Michael Fletcher, the bard of market-stall banter, has to get hideously tanked and coked up before he can find the words to tell the truth about his father’s racism to the congregation at his funeral.

The clever set (by Ultz), a bright scarlet raised walkway in the shape of a St George’s cross, allows the actors to stay close to the audience on all four sides of them, some in seats between two arms of the cross. Bananas fall from on high (a football racism reference). Spotlit at the cross’s ends are symbolic items the actors can lift down and put on low pllnths, the only scenery here. In Delroy these include a hair dryer that becomes the nagging voice of his girlfriend. Michael features a bust of Nefertiti that represents Denise, his mate Delroy’s scary Jamaican mum, and a brassy plate with a Medusa-ish face on it, which he depicts as his own mum, her eyes always drilling into him. These women are two major sources of his discomfort.

The clever set (by Ultz), a bright scarlet raised walkway in the shape of a St George’s cross, allows the actors to stay close to the audience on all four sides of them, some in seats between two arms of the cross. Bananas fall from on high (a football racism reference). Spotlit at the cross’s ends are symbolic items the actors can lift down and put on low pllnths, the only scenery here. In Delroy these include a hair dryer that becomes the nagging voice of his girlfriend. Michael features a bust of Nefertiti that represents Denise, his mate Delroy’s scary Jamaican mum, and a brassy plate with a Medusa-ish face on it, which he depicts as his own mum, her eyes always drilling into him. These women are two major sources of his discomfort.

The third is represented in a white floral tribute spelling out DAD, a reminder that after Alan Fletcher’s heart stopped, just as England lost to Croatia at the 2020 World Cup, his son Michael became the man of the family. Michael has always been seen as a poster-boy for Britishness who desperately wants to be like his father. But his mother cruelly dismisses this idea, just as he tells Delroy he will never be “one of us”. The more he speaks, the more he exposes unexpected facets of his personality beneath his slightly lardy, blokeish exterior; a sad man who doesn’t know what he stands for but knows it’s not what his father stood for. Or seemed to. For he will discover after his father’s death that he wasn’t exactly who Michael thought he was.

Thomas Coombes (pictured above) is a revelation in this role. The fine comic touch he displayed as the quizzical desk sergeant in Baby Reindeer is vital here, forcing us not to dismiss Michael out of hand as somebody we know all too well. He’s a stereotypical-looking “bloke” approaching middle age in the uniform of the teenager, white T-shirt and trainers, who’s gobby rather than yobby. But he is also entertaining and funny. More importantly, he’s revealed to be a sad, confused man, buoyed by his friendship with Delroy but then accused by his own mother of being more Black than white.

By his own account, his racist utterances aren’t a natural reflex, they are camouflage when his dad’s “nut-job mates” are round theirs. When his father dies, he’s lost. Coombes’s intelligence and subtlety deliver what the script lays out: a fascinating study of a man who desperately needs new bearings, and knows it, but doesn’t know how to find them.

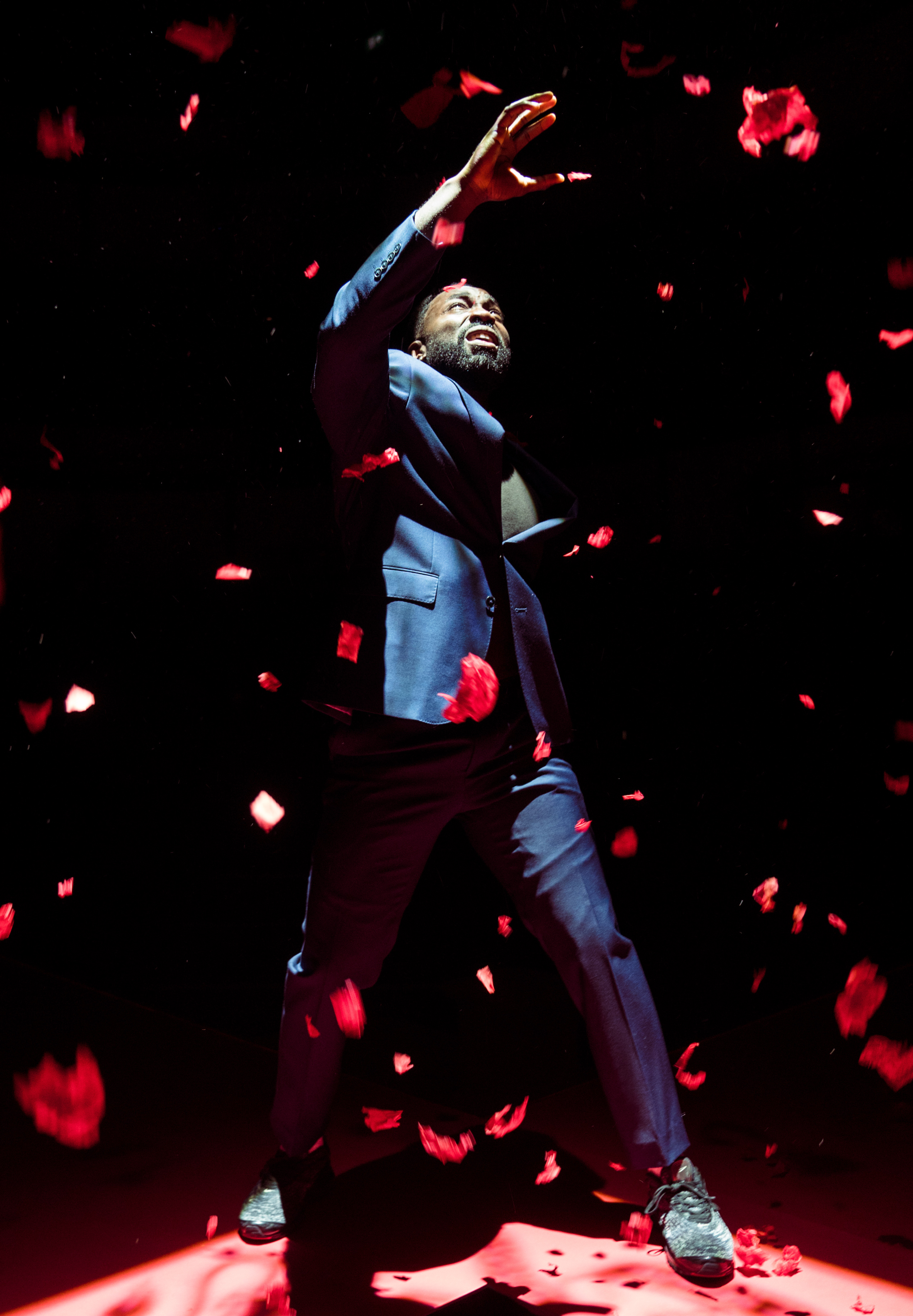

This is even more true of the thrilling performance by Paapa Essiedu as Delroy, a Brexit-voting bailiff with a killer right hook who blamelessly ends up on the wrong side of the law. Essiedu peoples the stage with all the main players in Delroy's life, with hilariously accurate accents and mannerisms – not just his mate Michael, but Michael’s tough-talking sister Carly, with whom he is besotted; the lisping officer who fits the security tag on his leg; the to-him risible miscreants whose possessions he and his band of bailiffs are appointed to take away. Supreme among them is his portrait of his mum, lips and chin drawn back in a defensive sneer, her hands tucked up above her waist, clasping at an invisible handbag.

But most potent of all is his portrayal of Delroy himself, who, as with Michael, turns out to be so much more than the stereotype his appearance and CV might suggest. This is an explosive, passionate man, a headstrong rebel, but also an aspirational one who works hard to better himself. He can be mouthy and accident-prone, but ultimately is an immensely poignant man who is trying to belong to the world around him – paradoxically, Michael’s white world – while mostly being rebuffed, including, he thinks, by his old mate Michael, the most hurtful of betrayals.

But most potent of all is his portrayal of Delroy himself, who, as with Michael, turns out to be so much more than the stereotype his appearance and CV might suggest. This is an explosive, passionate man, a headstrong rebel, but also an aspirational one who works hard to better himself. He can be mouthy and accident-prone, but ultimately is an immensely poignant man who is trying to belong to the world around him – paradoxically, Michael’s white world – while mostly being rebuffed, including, he thinks, by his old mate Michael, the most hurtful of betrayals.

Essiedu can switch between all of these personas with mercurial speed, stopping along the way to josh with members of the audience he has recruited to play extras in his mini-dramas. It’s his best performance in an excellent crowded CV that includes an RSC Hamlet, Kwame in I May Destroy You and, tellingly, the multiple characters of Caryl Churchill’s A Number.

Both plays climax with an extraordinary sustained rant, in which each man spells out why England is increasingly dead to him. Taken together, they leave us with twin portraits of men trying to dodge the dehumanising stereotypes imposed on their respective tribes – of the cool but silent Black “street” guy and the racist white nationalist, united only in their love of Leyton Orient. They are rebels, but without a clearcut cause.

The politics here are thrillingly unpredictable and suddenly hugely topical. They are are also savagely funny. Cutting through the men's raging is a surprisingly sage Carly, co-star with Denise of the third play, who punctures Delroy’s sense of victimhood with a sentence that shows her straddling the divide between their two working-class worlds: “You’re not in South Africa, bruv, you’re in Hackney, it ain’t that f***ing ‘ard.” If you saw these plays at the Dorfman, go again.

- The Death of England cycle at Soho Place, in rep until 28 September

- More theatre reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment