Schubert: Sonata in G major D. 894, Moments Musicaux D. 780, Fantasy in F minor D. 940 Maurizio Pollini, Daniele Pollini (pianos) (Deutsche Grammophon)

Schubert: Sonata in G major D. 894, Moments Musicaux D. 780, Fantasy in F minor D. 940 Maurizio Pollini, Daniele Pollini (pianos) (Deutsche Grammophon)

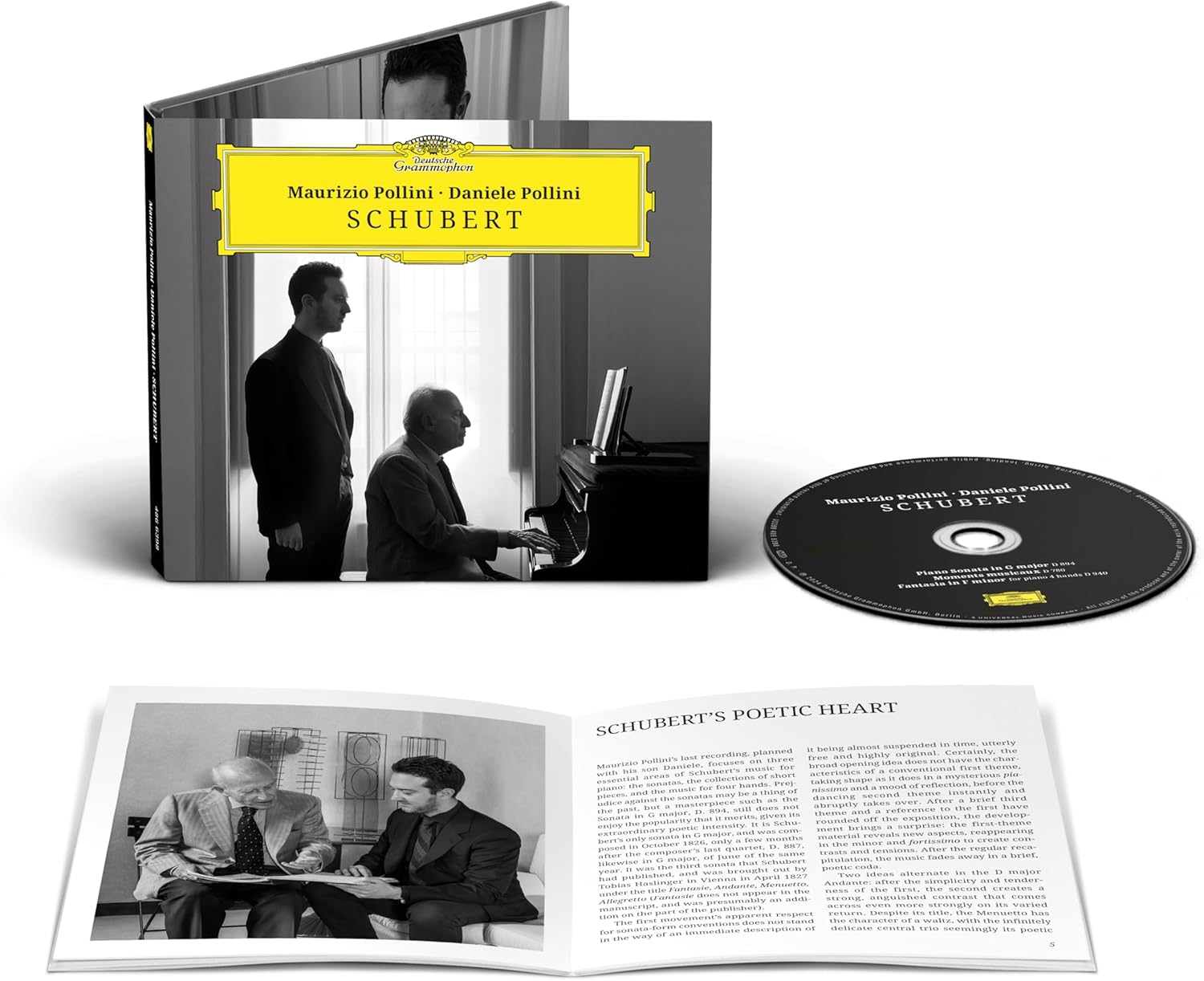

What a superb cover image for the last recording by Maurizio Pollini (1942-2024). Pollini ‘père’ is seated at the piano, backlit. His son Daniele (b.1978) stands behind him, looking over his shoulder. Cosimo Filippini’s photograph tells the story of this album so well. Pollini is in the role of the authoritative guide, as if teaching his son – and us listeners – lessons about this music. I can somehow imagine him repeating Paul Cézanne’s words to the young painter Émile Bernard: “I owe you the truth.” The recording, a Schubert programme by father and son was made in June 2022, just a few months after Maurizio Pollini’s 80th birthday, in the splendour of the Herkulessaal at the Residenz Palace in Munich.

Maurizio Pollini does have a particularly purposeful and consequential way with Schubert. His way in unfolding the opening movement of the Piano Sonata in G major, D 894 – which either Schubert or his publisher also called a ‘Fantasie’ almost fifteen minutes in duration – is to underline the miracle of its construction. The comparison with Elisabeth Leonskaja’s recent recording of this movement (which is more than five minutes longer) is instructive: Pollini plays with grandeur, what Edward Said has described as “aristocratically clear, powerfully and generously articulated”. Leonskaja goes deeper, and “opens [her] heart, to get the breadth”, as she told David Nice in an interview for this site.

After the Sonata, Pollini ‘fils’ plays the six Moments Musicaux D. 780. His best is the sixth in A flat, which he plays with wonderfully soft eloquence – and patience. Father and son conclude their three-part programme with the Fantasy in F Minor, for piano four hands – Daniele plays ‘primo’, Maurizio ‘secondo’. The main surprise here is how uncomfortably and impetuously fast they choose to take the ‘allegro vivace’ section. In the wake of his father’s death in March of this year, Daniele has said: “What was always going to be a very special occasion became something we’ll never be able to repeat. I’m very happy [...] to have played alongside my father on his final recording.” And there is certainly a poignancy about the final section of the Fantasy as father and son and Schubert find an impeccably gentle ending together, bringing Maurizio Pollini’s sixty-two year recording career to its conclusion. Farewell. Sebastian Scotney

J.S. Bach: Music Of The Heavens Adam Czerwiński (drums), Marcin Wądołowski (guitars), Alicja Śmietana (violin), Yaron Gershovsky (piano), John Medeski (keyboards) et al (AC Records)

J.S. Bach: Music Of The Heavens Adam Czerwiński (drums), Marcin Wądołowski (guitars), Alicja Śmietana (violin), Yaron Gershovsky (piano), John Medeski (keyboards) et al (AC Records)

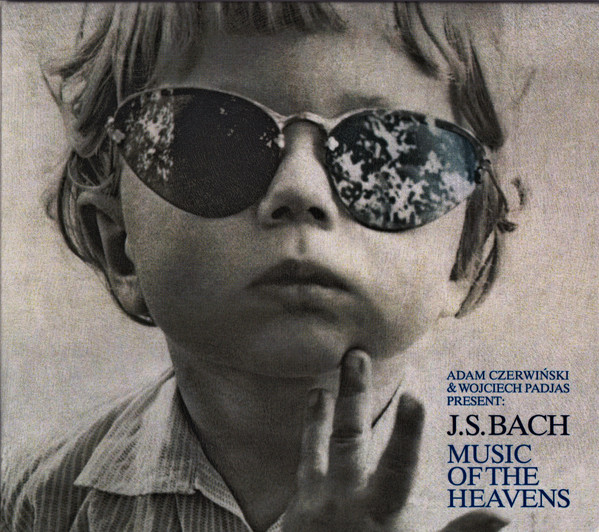

If there are readers out there for whom the 1960s/70s Bach-ian adventures of Wendy Carlos, Keith Emerson or Steve Howe produce a pang of nostalgia – rather than abject horror – please read on. (If the latter, then you know what to do). Drummer Adam Czerwiński and journalist/ radio host/entrepreneur Wojciech Padjas have put together a variety of approaches to treat eleven popular works by Bach as "standards" and then look at them through a jazz or rock prism. This new album follows on from the 2022 release Mozart Rocks & Swings, which included some of the players on this album. But whereas the Mozart album would depart from the source material straight away and rock out, this new Bach collection stays much closer to it. It has a similar vibe to that of Ensemble Resonanz’s recording of Christmas Oratorio from 2019, with an emphasis on provoking through bringing new sonic colours to the fore. An exception is a hard-swinging jazz piano version of Bach’s “Air on a G string” from Yaron Gershovsky

Violinist Alicja Śmietana is the daughter of one of Poland’s most popular jazz gods, guitarist Jarek Śmietana (1951-2013). Her violin solo contributions have a clarity and candour about them which are particularly appealing, notably the “Aria” from the Goldberg Variations, accompanied by vibraphone, bass guitar, and drums. AC Records is a vinyl club, and recording/ production are of very high quality. Sebastian Scotney

Dvořák: Cello Concerto, Tchaikovsky: Variations on a Rococo Theme John-Henry Crawford (cello), San Francisco Ballet Orchestra/Martin West (Orchid)

Dvořák: Cello Concerto, Tchaikovsky: Variations on a Rococo Theme John-Henry Crawford (cello), San Francisco Ballet Orchestra/Martin West (Orchid)

Dvořák: Cello Concerto, plus music by Silvestrov, Hanna Havrylets, Yuri Shevchenko and Stepan Charnetskyi Raphaela Gromes (cello), National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine/Volodymyr Sienko (Sony)

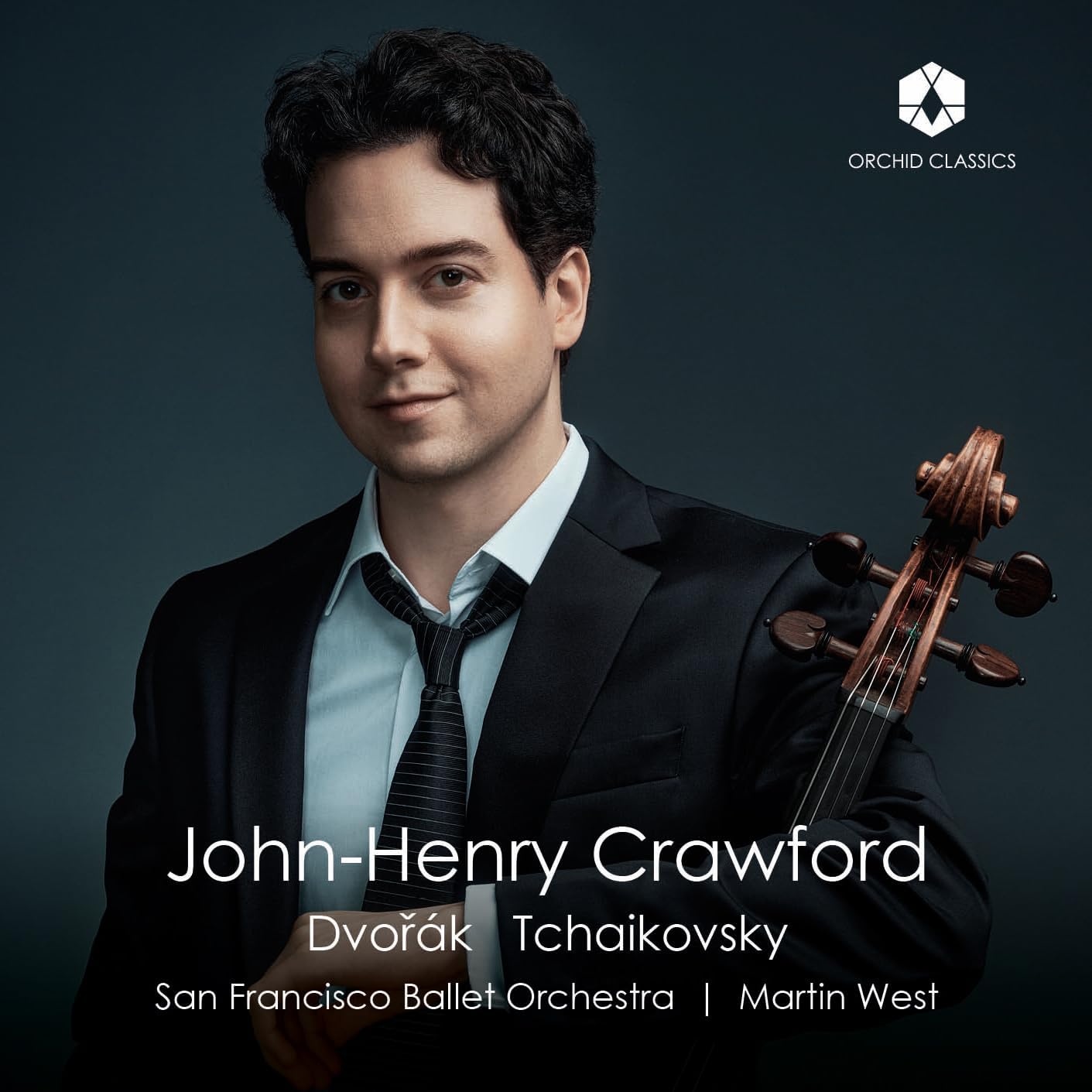

I’ve accrued a sizeable pile of Dvořák releases in recent months, starting with two new CDs of the Cello Concerto. One significant difference between them is their respective accompaniments: John-Henry Crawford is supported by Martin West’s fifty-piece San Francisco Ballet Orchestra, while Raphaela Gromes has a full-size National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine under Volodymyr Sirenko. The slimmer forces work in Crawford’s favour: West’s players, closely recorded, never overwhelm the soloist and we hear plenty of orchestral detail that’s too often buried. Dvořák’s horn writing is especially well served, with a melting solo in the concerto’s long introduction. Crawford’s rich, expressive playing is especially convincing in the central slow movement, and the opening of the finale has plenty of bite. Near the concerto’s close, the music slows and Dvořák quotes his own song “Kéž duch můj sám” as a tribute to his ailing sister-in-law. It’s a heart-stopping moment, beautifully handled here, casting a shadow over the assertive final bars. Crawford’s coupling is Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations, heard (as is usually the case) in the revised edition made by dedicatee Wilhelm Fitzenhagen. Woodwinds excel and there’s plenty of sparkle in the faster sections. And I really like the ambience of this recording, taped at George Lucas’s Skywalker Sound in March 2023

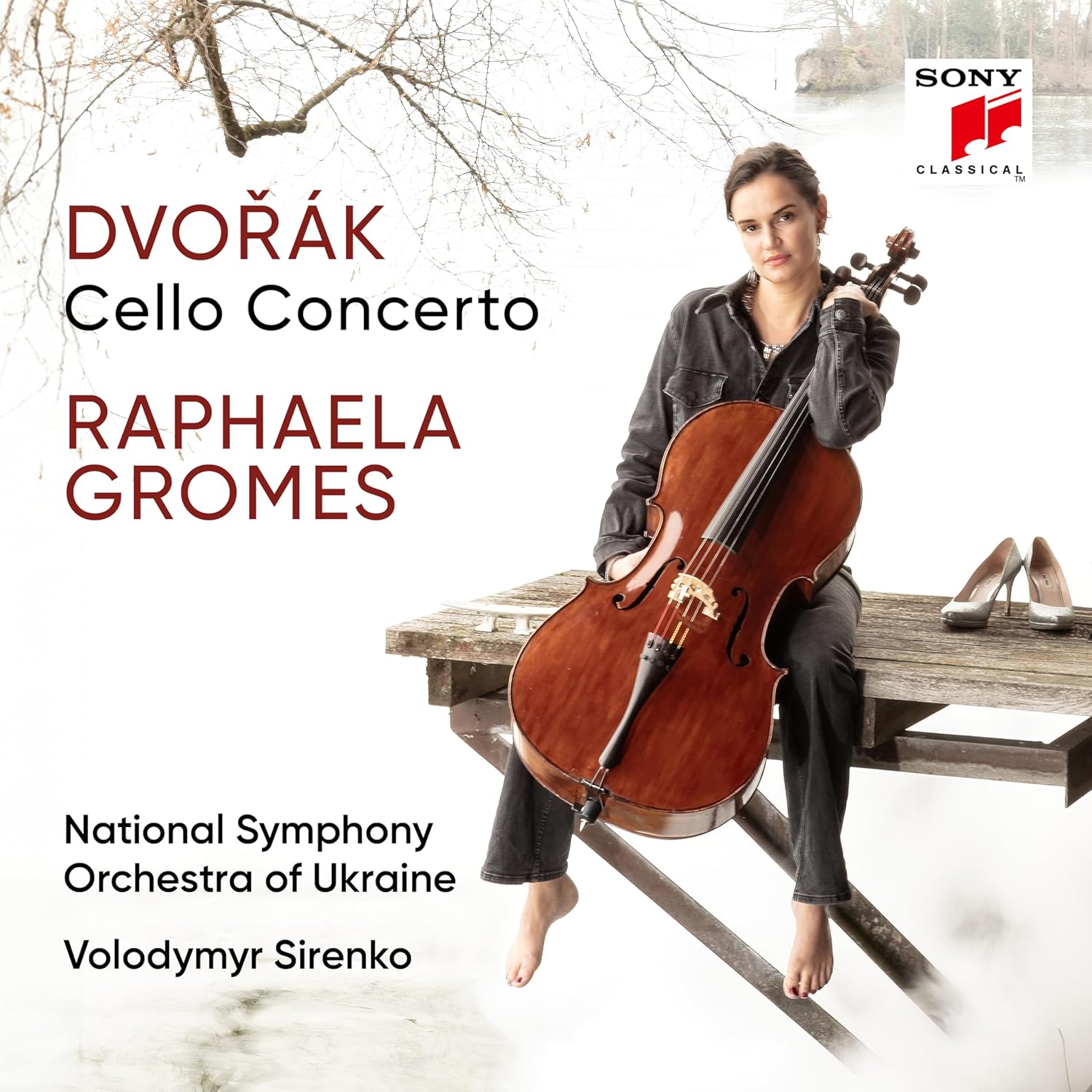

Raphaela Gromes’s flowing speeds in the Dvořák are similar to Crawford’s, though she’s a touch slower in the slow movement. This disc was recorded in Lublin, Poland, instead of Kyiv, Gromes’s insurers advising against taking her valuable Bergonzi cello into a war zone. Circumstances permitted a longer rehearsal process than would normally be the case, Gromes recalling a desire to look at the score in detail and return the piece to its Bohemian origins. I’m always wrongfooted by the length of Dvořák’s opening tutti, and Gromes’s entry at 3’30” is bold and authoritative. As with the Orchid disc, the orchestral playing is impressive, Sirenko and his soloist making sparks fly in the first movement’s exultant coda. I like Gromes’s rapt take on the “Adagio, ma non troppo”, aided by some lovely wind solos, and she’s as feisty as Crawford in the finale. The final minutes are gorgeous. You’ve a hard heart if this music doesn’t induce tears, the circumstances in which this performance was recorded made giving it extra poignancy. We get interesting couplings too: Silvestrov’s recent Prayer for the Ukraine heard alongside three other works by Ukrainian composers. Yuri Shevchenko’s We Are, based on the Ukrainian anthem, packs a punch, as does Hanna Havrylets’ Tropar, Prayer to the Holy Mother of God: the notes reveal that Havrylets died prematurely of heart failure in February 2022, the invasion meaning that the medical support she needed could not be provided.

Raphaela Gromes’s flowing speeds in the Dvořák are similar to Crawford’s, though she’s a touch slower in the slow movement. This disc was recorded in Lublin, Poland, instead of Kyiv, Gromes’s insurers advising against taking her valuable Bergonzi cello into a war zone. Circumstances permitted a longer rehearsal process than would normally be the case, Gromes recalling a desire to look at the score in detail and return the piece to its Bohemian origins. I’m always wrongfooted by the length of Dvořák’s opening tutti, and Gromes’s entry at 3’30” is bold and authoritative. As with the Orchid disc, the orchestral playing is impressive, Sirenko and his soloist making sparks fly in the first movement’s exultant coda. I like Gromes’s rapt take on the “Adagio, ma non troppo”, aided by some lovely wind solos, and she’s as feisty as Crawford in the finale. The final minutes are gorgeous. You’ve a hard heart if this music doesn’t induce tears, the circumstances in which this performance was recorded made giving it extra poignancy. We get interesting couplings too: Silvestrov’s recent Prayer for the Ukraine heard alongside three other works by Ukrainian composers. Yuri Shevchenko’s We Are, based on the Ukrainian anthem, packs a punch, as does Hanna Havrylets’ Tropar, Prayer to the Holy Mother of God: the notes reveal that Havrylets died prematurely of heart failure in February 2022, the invasion meaning that the medical support she needed could not be provided.

Voices Hanni Liang (piano) (Delphian)

Voices Hanni Liang (piano) (Delphian)

Hanni Liang is a pianist of Chinese heritage who lives and works in Germany and who “specialises in developing new concert formats”. That said, this is a pretty standard recital album, her first full-length release, featuring exclusively music by women composers, from Ethel Smyth (born in 1858) to Sally Beamish (born in 1956). Liang was inspired by reading a biography of Ethel Smyth, whose life and personality were indeed fascinating, notable and blazed a trail for women in British musical life. At the same time I have always felt her music is nothing like as interesting as she was herself, and the two pieces here don’t really shift that view. That said, they are worth their place in the catalogue, especially as there hasn’t been a recording of Smyth’s piano music since the 1990s, and they make interesting points of contact with the music of later women composers.

Both pieces date from her late teens, in 1877 and 1878, the time when she was studying in Germany. There is a lot of Brahms and Schumann in there, but also a youthful lightness, in the Finale of the Sonata no.2, which Liang captures delightfully. The wryly-named Variations in D flat major on an Original Theme (of an Exceeding Dismal Nature) – are in fact far from dismal. After a quiet theme the variations have assurance in their development of the material and the piano writing. Liang is good in the stern second variation but the heart of the set is variation V, where she finds an emotional range that is impressive in the young composer.

The Smyth pieces are set against pieces by four living composers. Errollyn Wallen’s brief I Wouldn’t Normally Say is spry and lively, which keeps feeling like it is going to burst into song. Sally Beamish’s Night Dances is unsettled and unsettling at first, the edgy evocation of a mind trying to sleep. The dances of the title are in the middle, wild and jazzy intoxicating. Chen Yi’s appealing Variations on “Awariguli” date from 1978, and are a nod to Liang’s Chinese heritage. The piece is based on a Uyghur folksong, which gives it an added resonance in the light the recent Chinese persecution. But the music has no hint of that, instead traversing a range of western musical styles with facility, including Bachian fugue and Debussyan wash. But perhaps the most arresting piece on the disc is the last, Eleanor Alberga’s Cwicseolfor, the ancient spelling of “quicksilver”. And mercurial it certainly is. By turns spiky, dreamy, liquid and punchy, it’s technically extremely demanding and Liang gives a highly entertaining performance. Bernard Hughes

Peter Seabourne: My Song in October (Steps Vol. 8) Michael Bell (piano), with Karen Radcliffe (soprano) (Sheva Contemporary)

Peter Seabourne: My Song in October (Steps Vol. 8) Michael Bell (piano), with Karen Radcliffe (soprano) (Sheva Contemporary)

Nicely timed for autumn, the eighth volume of Peter Seabourne’s series of piano pieces is a reflective set of “album leaves, borne on the whims of the wind”. Seabourne began by collecting a set of 19 poems making references to leaves, the number 19 alluding both to the date of Seabourne’s wife’s recent death from cancer, and to the letter S being the 19th letter of the alphabet. Not that this sequence of miniatures makes for depressing or maudlin listening, the composer’s aim being to portray the sight of falling leaves, “whether gently, whimsically, melancholically or in a flurry.” The original poems are included in the booklet, the assorted poets including Goethe, Kathleen Raine, Verlaine and Longfellow. Highlights include two contrasting numbers inspired by Shelley and No. 14’s “Every Breath”, where tinkling bell sounds are answered by solemn chords. Bells return in the elegiac closer, suggested by Ted Hughes’ “Elegy for the Leaves”.

This isn’t easy music to bring off, Seabourne’s language both flamboyant and introspective. Pianist Michael Bell is a superb guide, and he’s also the accompanist in the song cycle September, Just Septembers. This was taped in 2004 with Bell’s wife, soprano Karen Radcliffe; and it’s been newly remastered for rerelease as a tribute to Radcliffe, who also lost her life to cancer. Seabourne sets nine poems by Emily Dickinson, sequenced to suggest a progression from summer to winter. Radcliffe is terrific throughout, stentorian in “Wild Nights” and hushed in “She bore it”, negotiating Seabourne’s angular but lyrical lines with ease. Especially effective is “The Sky is Low”, Bell’s twisting single line intermittently coinciding with Radcliffe’s. Production values are impressive, with detailed commentaries on both works and full texts included.

That Sweet City Choir of the Queen’s College, Oxford, Britten Sinfonia/Owen Rees, with Nick Pritchard (tenor), Rowan Atkinson (narrator) (Signum Classics)

That Sweet City Choir of the Queen’s College, Oxford, Britten Sinfonia/Owen Rees, with Nick Pritchard (tenor), Rowan Atkinson (narrator) (Signum Classics)

Voices of Thunder Choir of Magdalen College, Oxford/Mark Williams (Coro)

These two albums, released a week apart by Oxford college choirs located a few hundred metres apart, seemed to be deserving of a joint review. They both speak to the ongoing health of Oxbridge collegiate singing, where there is the financial support for choirs who sing liturgically several times a week to venture beyond that repertoire in commercial recordings. The Choir of the Queen’s College, under Owen Rees, pair two pieces premiered at the college in the early 1950s, one by a young Kenneth Leighton and the other by an elderly Ralph Vaughan Williams. The Leighton is Veris Gratia, an undergraduate piece based on Latin texts from the Carmina Burana, stylistically as far from Carl Orff as it is very close to Vaughan Williams. Dedicated to Leighton’s friend Gerald Finzi, it is in the mid-century pastoral English idiom, for choir and chamber orchestra, missing the bracing rhythms and dissonances of the later Leighton. Tenor Nick Pritchard is on characteristically eloquent form in his two solos, David Cuthbert’s flute solo in the instrumental, Finzi-ish “Elegy” is restrained and poised, and the choir assured, especially in the richer harmonic world of the “Eclogue”, supporting an unnamed (but very good) soprano soloist from the choir’s ranks. Perhaps the best movement is the “Paean”, which has a bit more vigour than elsewhere. Vaughan Williams’s An Oxford Elegy, from the other end of a compositional career, is not a piece I knew, although it is quite well-represented in the recording catalogue. This new version is narrated by Rowan Atkinson, who plays it straight – or as straight as he can ever manage. He doesn’t really do gravitas – his voice is light, although infinitely flexible – and I prefer Jeremy Irons’ narration on the London Mozart Players recording from 2014, although the present album wins out for quality of sound. That aside, the playing (by the Britten Sinfonia) is subtle, especially in the winds, and the choir’s part warmly sung. The tone is elegiac, of course, but also nostalgic and loving.

The Magdalen choir album is designed to showcase the new Eule organ in the college’s chapel, with organist duties shared between Alexander Pott, Edward Byrne and Romaine Bornes (the latter two the current organ scholars) and Mark Williams conducting. I am no organ geek, and the detailed pages of notes explaining the construction and combination of stops largely went over my head, but it certainly sounds very good. The opening track, James MacMillan’s A New Song gives full vent to its bass and sub-bass register only using the full organ in the magnificent playout. By contrast, Jonathan Dove’s Seek him that maketh the seven stars is bright and trebly, dancing around the slow-moving choir. Balfour Gardiner’s Evening Hymn begins with a marvellously paced organ crescendo, and the choir match this opulence in their singing. The rest of the programme is mostly music in the British cathedral tradition, but of those that aren’t, Marcel Dupré’s Laudate Dominum is loud and proud, and Arvo Pärt’s The Beatitudes very much isn’t. It proceeds in Pärt’s usual holy minimalist fashion – till the final “Amen”, which bursts into an unexpected organ radiance, that slowly subsides to nothing, the reverse procedure to the Balfour Gardiner. The organists all do the instrument proud and the choir are in good voice, not least in Parry’s evergreen, joyful Blest Pair of Sirens that rounds off the disc. Bernard Hughes

The Magdalen choir album is designed to showcase the new Eule organ in the college’s chapel, with organist duties shared between Alexander Pott, Edward Byrne and Romaine Bornes (the latter two the current organ scholars) and Mark Williams conducting. I am no organ geek, and the detailed pages of notes explaining the construction and combination of stops largely went over my head, but it certainly sounds very good. The opening track, James MacMillan’s A New Song gives full vent to its bass and sub-bass register only using the full organ in the magnificent playout. By contrast, Jonathan Dove’s Seek him that maketh the seven stars is bright and trebly, dancing around the slow-moving choir. Balfour Gardiner’s Evening Hymn begins with a marvellously paced organ crescendo, and the choir match this opulence in their singing. The rest of the programme is mostly music in the British cathedral tradition, but of those that aren’t, Marcel Dupré’s Laudate Dominum is loud and proud, and Arvo Pärt’s The Beatitudes very much isn’t. It proceeds in Pärt’s usual holy minimalist fashion – till the final “Amen”, which bursts into an unexpected organ radiance, that slowly subsides to nothing, the reverse procedure to the Balfour Gardiner. The organists all do the instrument proud and the choir are in good voice, not least in Parry’s evergreen, joyful Blest Pair of Sirens that rounds off the disc. Bernard Hughes

- More Classical reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment