Fauré Centenary Concert 5, Wigmore Hall review - a final flight | reviews, news & interviews

Fauré Centenary Concert 5, Wigmore Hall review - a final flight

Fauré Centenary Concert 5, Wigmore Hall review - a final flight

The master of levitation in transcendent performances from Steven Isserlis and friends

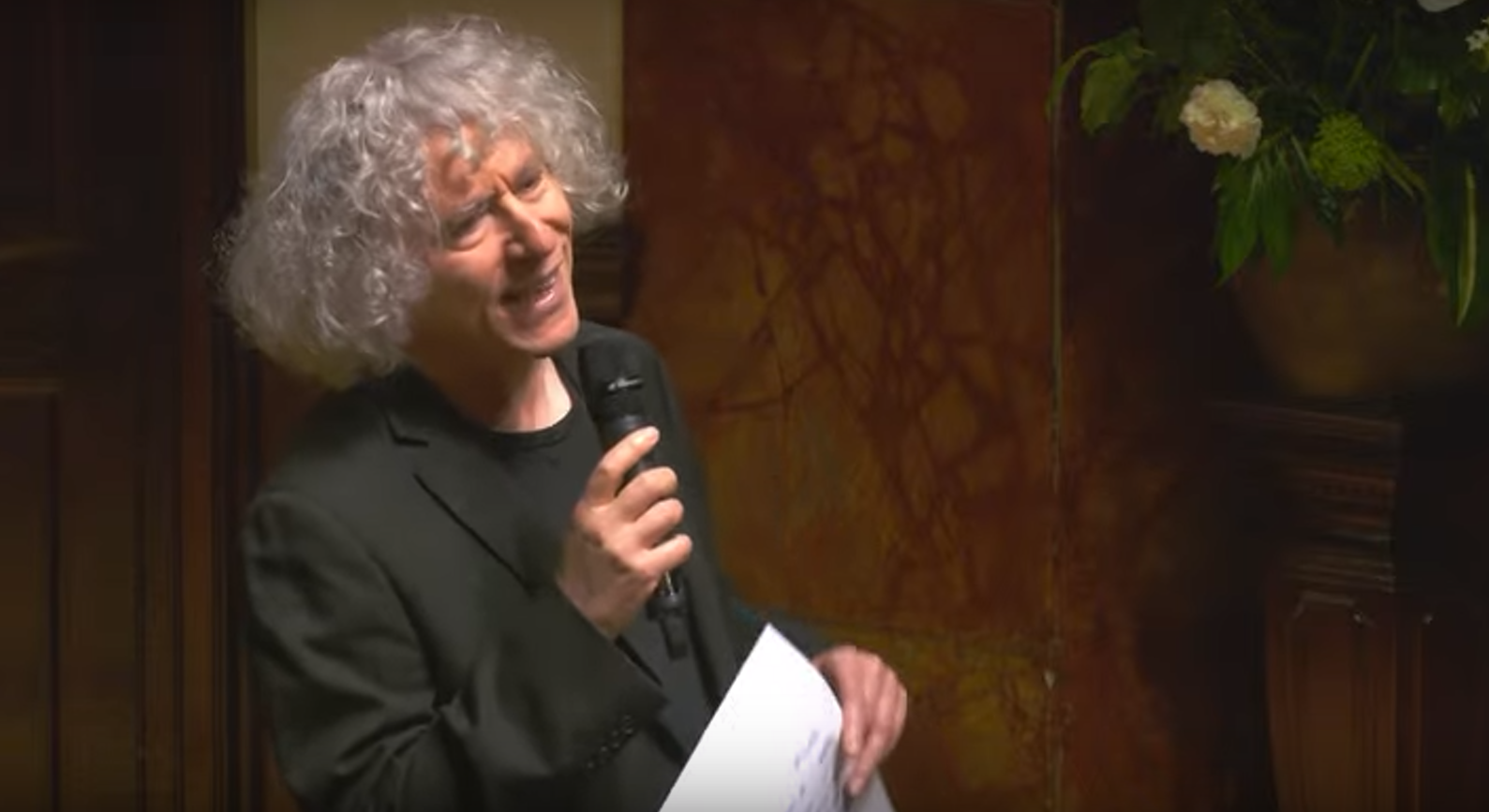

As Steven Isserlis announced just before the final work, in more senses than one, of a five-day revelation, the 79 year old Fauré’s last letter told his wife that “at the moment I am well, very well, despite the little bout of fatigue which is caused by the end of the Quartet. I am happy with everything, and I should like everyone to be happy all around me, and everywhere”.

The world is an unhappier place than ever this morning, yet somehow that incandescent performance of a uniquely beautiful string quartet made things not so hard. Today there’s calm resignation, though that probably won’t, and shouldn’t, last. In the meantime, let’s celebrate what six good, supremely gifted people have given us, whether you were in the hall – as, alas, I was only able to be for the first and last concerts – or watching online (the treasury of Wigmore live performances on YouTube has hit new heights with these five peerless concerts).

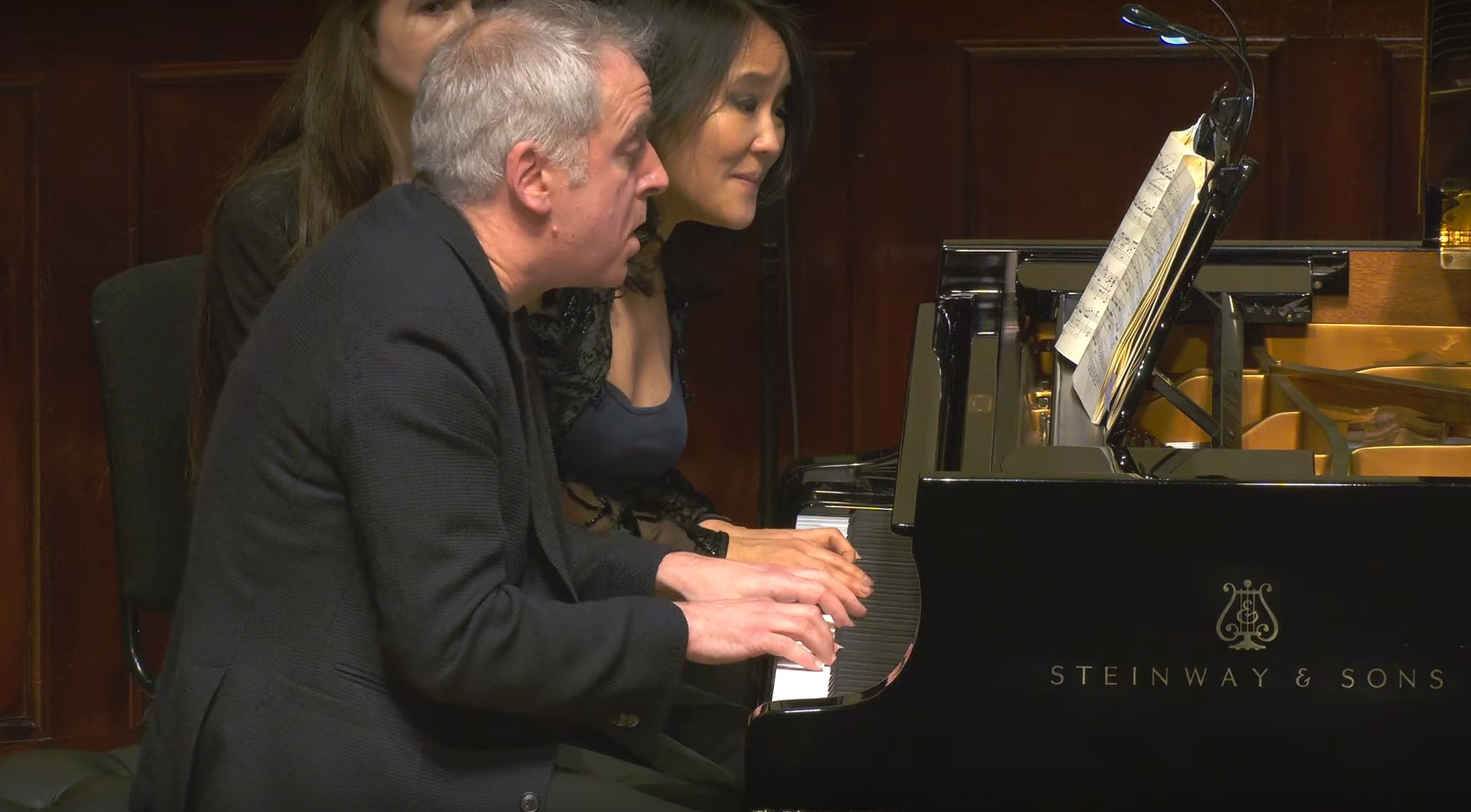

Nothing is quite as straightforward as it seems even in Fauré's supposedly simpler pieces. Young Helene Bardac, aka "Dolly", must have been accomplished at an early age to play the four-hand arrangements of the eponymous Suite with her mentor. Harmonically, the six pieces are stamped with the composer's adventurousness, however subtle. Even the opening "Berceuse," still resonating for those of us old enough to remember radio's "Listen with Mother", takes some surprising excursions in its middle sequence. This still seems to be music about, more than for, children: "Tendresse" has a very adult perspective of heartbreaking love. Nevertheless Jeremy Denk and Connie Shih (pictured above) made light of it all in the best sense; no other pianists could go so effortlessly beneath the charming surface.

This still seems to be music about, more than for, children: "Tendresse" has a very adult perspective of heartbreaking love. Nevertheless Jeremy Denk and Connie Shih (pictured above) made light of it all in the best sense; no other pianists could go so effortlessly beneath the charming surface.

Denk introduced in his own inimitable narrative style three homages to the master from distinguished pupils on Fauré's 77th birthday, Not my place to go in to how you extract musical notes from the five letters of his name (the programme note should have done that). Suffice it to say that wizard Enescu wraps them in mystery, Ravel goes for an initially straightforward and lovely play on "Gabriel" as well as "Fauré" before conjuring magic himself, and Koechlin similarly mixes simplicity and complexity in a slightly more meandering way.

How does Fauré's late style avoid a sense of that meandering other than in a wholly positive sense? Does it defy analysis? At any rate, there was plenty of contrast in the balance between Isserlis and Shih for the Second, G minor, Cello Sonata of 1921: miraculous, seamless dialogues in the first and third movements, centre stage for long melodies from the cello in the second, where Isserlis pulled back into an almost disembodied incantation halfway through. He's been playing the work since he was 15, but he must keep finding ever more beneath its sphinx-like surface.  Isserlis confessed that at one stage he didn't "get" the swansong String Quartet, that it was the performers' job to make as much as possible clear for the listener. At times this involves a kind of transcendental meditation, but you're aware, above all in the central Andante, of Bell's ecstatic tone at climaxes, of supernatural harmonies, a vision of climbing spiral staircases between earth and heaven that shimmer like the Aurora Borealis. Supply your own images: if this supposedly abstract music doesn't provoke them, I'd be surprised. How wonderful, too, that in the finale pizzicati comments on all that striving especially from second violin (Duval) and cello suggest there's still enough to tie the dying composer to the earth. Nothing matters in one sense, everything in another. No wonder Isserlis called this series the most rewarding challenge of his life: "it's all downhill from now on". I suspect not.

Isserlis confessed that at one stage he didn't "get" the swansong String Quartet, that it was the performers' job to make as much as possible clear for the listener. At times this involves a kind of transcendental meditation, but you're aware, above all in the central Andante, of Bell's ecstatic tone at climaxes, of supernatural harmonies, a vision of climbing spiral staircases between earth and heaven that shimmer like the Aurora Borealis. Supply your own images: if this supposedly abstract music doesn't provoke them, I'd be surprised. How wonderful, too, that in the finale pizzicati comments on all that striving especially from second violin (Duval) and cello suggest there's still enough to tie the dying composer to the earth. Nothing matters in one sense, everything in another. No wonder Isserlis called this series the most rewarding challenge of his life: "it's all downhill from now on". I suspect not.

- Watch the five centenary concerts on the Wigmore Hall's YouTube channel

- More classical reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

BBC Proms: Ehnes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson review - aspects of love

Sensuous Ravel, and bittersweet Bernstein, on an amorous evening

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Presteigne Festival 2025 review - new music is centre stage in the Welsh Marches

Music by 30 living composers, with Eleanor Alberga topping the bill

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

Lammermuir Festival 2025 review - music with soul from the heart of East Lothian

Baroque splendour, and chamber-ensemble drama, amid history-haunted lands

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

BBC Proms: Steinbacher, RPO, Petrenko / Sternath, BBCSO, Oramo review - double-bill mixed bag

Young pianist shines in Grieg but Bliss’s portentous cantata disappoints

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

theartsdesk at the Lahti Sibelius Festival - early epics by the Finnish master in context

Finnish heroes meet their Austro-German counterparts in breathtaking interpretations

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Classical CDs: Sleigh rides, pancakes and cigars

Two big boxes, plus new music for brass and a pair of clarinet concertos

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

Waley-Cohen, Manchester Camerata, Pether, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester review - premiere of no ordinary violin concerto

Images of maternal care inspired by Hepworth and played in a gallery setting

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

BBC Proms: Barruk, Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Kuusisto review - vague incantations, precise laments

First-half mix of Sámi songs and string things falters, but Shostakovich scours the soul

Add comment