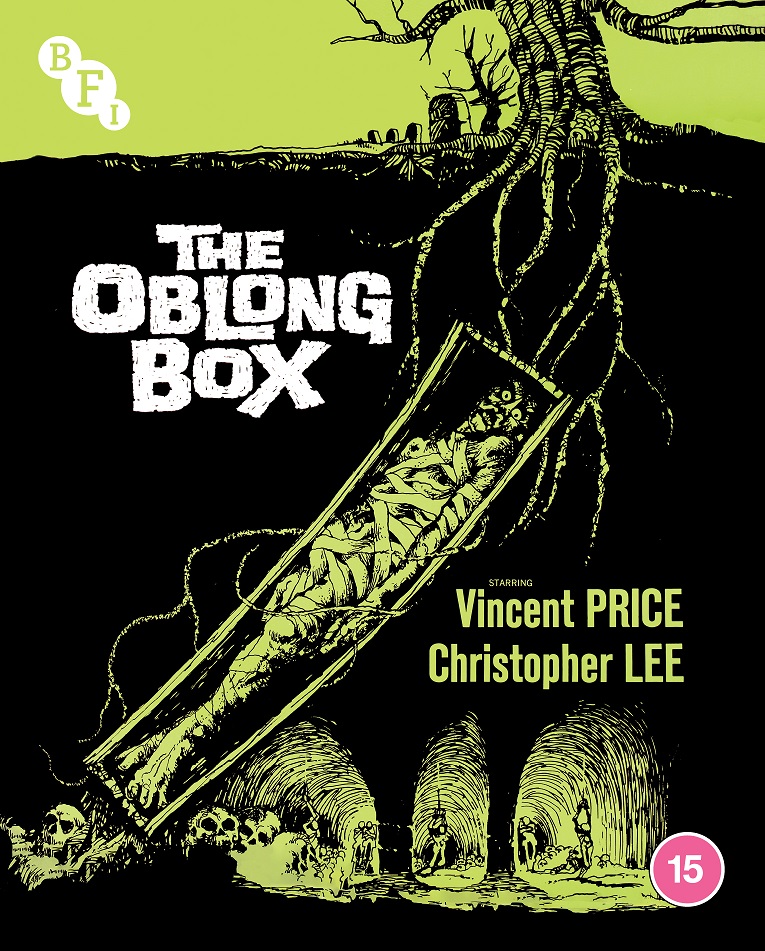

The Oblong Box is a phantom 1969 follow-up to Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General, sharing star Vincent Price and much cast and crew, after the brilliant young British director’s OD forced his dismissal days before shooting. It also began replacement Gordon Hessler and co-writer Christopher Wicking’s own Price-starring horror sequence, notably the bizarre, Mod anti-fascist Scream and Scream Again (1970), placing this obscure film at a packed cult crossroads.

Witchfinder General’s savage account of Matthew Hopkins’ 17th century East Anglian rampage had been dragooned into AIP’s Poe-Price cycle in the US. Its great success led to The Oblong Box, which parlays Poe’s premature burial theme into a richer genre brew of voodoo, body-snatching, torture and a mad sibling in the attic, centred on Sir Julian (Price)’s disfigured brother Sir Edward (Alister Williamson), properly seen only at the end.

Witchfinder General’s savage account of Matthew Hopkins’ 17th century East Anglian rampage had been dragooned into AIP’s Poe-Price cycle in the US. Its great success led to The Oblong Box, which parlays Poe’s premature burial theme into a richer genre brew of voodoo, body-snatching, torture and a mad sibling in the attic, centred on Sir Julian (Price)’s disfigured brother Sir Edward (Alister Williamson), properly seen only at the end.

Reeves and Wicking’s most significant reworking of Lawrence Huntingdon’s original script roots the horror in colonial crimes. Hessler makes the wild prologue of a half-glimpsed white man’s African crucifixion and ritual disfigurement a riot of fish-eyed distortion and contorted close-ups of a red-eyed, knife-wielding shaman, a ceremony interrupted by Julian, who cries out for his brother. Back in his English country manor, Julian chains crazed Edward in a secret room, and plans to sell his African plantation “before it’s too late”. “I’ve seen what Africa can mean,” he tells innocent young wife to be Elizabeth (Witchfinder General’s female lead Hilary Dwyer), “and what we’ve come to mean to Africa.” Edward has meanwhile imported witch doctor N’Galo (Harry Baird) to place him in a death-like trance then revive him from his grave.

The heady sadism which gave Witchfinder General its visceral power intermittently pulses. The anti-colonial theme in the decade of African independence, like the shoving at censorship’s limits – sensational violence, a bared nipple – show this is 1969, when even Gothic horror quit the sinister elegance of Terence Fisher’s Hammer films a decade earlier. Wicking and Reeves were both in their early twenties (Hessler was 45) and depict an ageing, corrupt ruling class and their cynical functionaries, such as Christopher Lee’s chilly patrician Dr Neuhartt, recipient of snatched and especially killed corpses. Hessler dissolves from funeral piety to a murdered body’s dumping, and Julian asking Elizabeth to dance to a corpse’s cutting. The grim ending meanwhile chimes with not only Witchfinder General and Night of the Living Dead, but 1969’s Easy Rider.

The heady sadism which gave Witchfinder General its visceral power intermittently pulses. The anti-colonial theme in the decade of African independence, like the shoving at censorship’s limits – sensational violence, a bared nipple – show this is 1969, when even Gothic horror quit the sinister elegance of Terence Fisher’s Hammer films a decade earlier. Wicking and Reeves were both in their early twenties (Hessler was 45) and depict an ageing, corrupt ruling class and their cynical functionaries, such as Christopher Lee’s chilly patrician Dr Neuhartt, recipient of snatched and especially killed corpses. Hessler dissolves from funeral piety to a murdered body’s dumping, and Julian asking Elizabeth to dance to a corpse’s cutting. The grim ending meanwhile chimes with not only Witchfinder General and Night of the Living Dead, but 1969’s Easy Rider.

Though a murderous, red-hooded monster, politely spoken Edward also seems an innocent victim as he’s spun around a rough London tavern. His sighting by a society ball’s screaming guests explicitly mirrors Frankenstein, and there is some melancholy to his vengeful rampage.

Price had wished for a happier collaboration with Reeves, following Witchfinder General’s fractious shoot and artistic success, but isn’t truly inspired in this inferior film. Rather than Reeves’ single-minded classic it recalls Scream and Scream Again’s intriguing mash-up of subversive ideas. Hessler and Wicking’s last film with Price, 1970’s compromised witch-hunting riff Cry of the Banshee, was a tawdrier descent into the new decade, whose illicit seediness is its principle virtue. The Oblong Box’s return of the African and English repressed and hallucinatory plantation prologue are perhaps the last of Reeves’ crucial spirit, before his final, fatal overdose prior to its release. Film historian Steve Haberman’s commentary fills in The Oblong Box’s production history and its makers’ rich hinterland, from composer Harry Robertson, also behind the swashbuckling theme of Hammer’s erotic vampire film Twins of Evil (1971) and Nick Drake’s “River Man” strings, to Witchfinder General’s returning cinematographer John Coquillon, retained by Hessler till recruited by Peckinpah. Wicking oversaw or wrote Hammer’s arresting Seventies death-throes (Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb, To the Devil a Daughter), and Julien Temple’s ill-fated Colin MacInnes musical Absolute Beginners (1986). Hitchcock TV show veteran Hessler made vigorous Harryhausen adventure The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) before fading back into TV.

Film historian Steve Haberman’s commentary fills in The Oblong Box’s production history and its makers’ rich hinterland, from composer Harry Robertson, also behind the swashbuckling theme of Hammer’s erotic vampire film Twins of Evil (1971) and Nick Drake’s “River Man” strings, to Witchfinder General’s returning cinematographer John Coquillon, retained by Hessler till recruited by Peckinpah. Wicking oversaw or wrote Hammer’s arresting Seventies death-throes (Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb, To the Devil a Daughter), and Julien Temple’s ill-fated Colin MacInnes musical Absolute Beginners (1986). Hitchcock TV show veteran Hessler made vigorous Harryhausen adventure The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) before fading back into TV.

This BFI Blu-ray debut’s new interview with Price’s daughter Victoria recalls his happy Anglophile haunting of Portobello Road antique stalls and museums on his English sojourns, and Oblong Box-simpatico West African art collection. The best of three era-spanning Poe shorts is actor-director Castleton Knight’s Prelude (1927), combining Rachmaninov with Poe’s “The Premature Burial”. Its dream-like dissolves, worm’s eye funeral view and close-up on the buried man’s panic through gauzy coffin wood are surreally nightmarish.

Add comment