Tate Britain’s Lee Miller retrospective begins with a soft focus picture of her by New York photographer Arnold Genthe dated 1927, when she was working as a fashion model. The image is so hazy that she appears as dreamlike and insubstantial as a wraith.

It exemplifies one of the hallmarks of a good model – the ability to become a screen that invites projection, rather than expressing your own personality. And in shot after shot for British and American Vogue, Miller remains an enigma – impassive and searingly beautiful. Would the exhibition bring her into sharper focus, as I hoped, or would she remain elusive?

For her posing for the camera was second nature; since the age of seven she’d been doing it for her father, a keen amateur photographer. He also taught her how to take and print photographs, and soon she would be working on both sides of the lens – as both the photographer and the model for Vogue fashion shoots.

Miller was clearly a restless spirit; her life was characterised by a series of abrupt moves from one continent to another prompted, I imagine, by curiosity and the desire to be reinvigorated by a change of scene. She wanted to be part of the action wherever it was playing out – whether for good or bad – and this paved the way for a remarkable life story.

Miller was clearly a restless spirit; her life was characterised by a series of abrupt moves from one continent to another prompted, I imagine, by curiosity and the desire to be reinvigorated by a change of scene. She wanted to be part of the action wherever it was playing out – whether for good or bad – and this paved the way for a remarkable life story.

Armed with a letter of introduction from the influential photographer Edward Steichen, in 1929 she left New York for Paris where she knocked on the door of the artist/photographer Man Ray and invited herself into his life. It was the beginning of an incredibly creative collaboration in which the distinction between artist and model disappeared – so much so, that it is often impossible to distinguish her input from his, especially as Man Ray often laid claim to images that were jointly created.

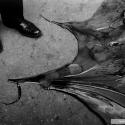

Miller continued to model meanwhile – for French Vogue – and opened her own photography studio. She also took her camera everywhere she went in case something caught her eye. On show, for instance, is a pool of tar oozing incongruously across a pavement (main picture) and a hand silhouetted against the Paris sky.

Among her friends were many Surrealists, and the exhibition curators are keen to claim her as one of them. But I see no reason to pigeonhole her like this, since her keen eye for the comedy or pathos of random occurrences remains fresh to this day. Surrealist imagery, on the other hand, often feels dated and contrived. A case in point is Jean Cocteau’s film Le Sang d’un poete 1930, which is laughably unconvincing; on show is a clip featuring the poet, played by a topless hunk, and Lee Miller as his armless muse.

Returning to New York in 1932, she set up Lee Miller Studios Inc to promote her work, but was off again two years later, this time to Cairo, having married an Egyptian businessman. Released from the pressure of earning a living, she was now free to hone her skills as a roving eye adept at capturing the strange, the odd and the unexpected.

Pithy titles often add humour or depth. Portrait of Space 1937 (pictured above right), for instance, features a view of the desert framed by a torn fly screen on which hangs a mirror reflecting nothing but emptiness. The pictures are characterised by unusual angles, viewpoints or framing that make the mundane seem strange. Silhouetted against the sky, the steel chimneys of the Helwan cement factory, for instance, appear to defy spatial logic, while a dainty light poking into space between the phallic shafts adds comedy to the drama.

After five years, she’d had enough. Itchy feet and an affair with British artist Roland Penrose (who would later found the Institute of Contemporary Arts) brought her to London in 1939. She began taking photographs for British Vogue and, as the second world war progressed, used London’s ruined streets as a backdrop for stylish fashion shoots. She rarely photographed the devastation caused by the blitz, preferring instead to retaliate with mordant humour. The smashed typewriter in Remington silent 1940 (pictured below right) is, for instance, a wry comment on the murderous chaos of war and also a riff on the company’s claim to make noiseless machines.

After five years, she’d had enough. Itchy feet and an affair with British artist Roland Penrose (who would later found the Institute of Contemporary Arts) brought her to London in 1939. She began taking photographs for British Vogue and, as the second world war progressed, used London’s ruined streets as a backdrop for stylish fashion shoots. She rarely photographed the devastation caused by the blitz, preferring instead to retaliate with mordant humour. The smashed typewriter in Remington silent 1940 (pictured below right) is, for instance, a wry comment on the murderous chaos of war and also a riff on the company’s claim to make noiseless machines.

She also produced features on the women who were helping the war effort by working in the factories or as nurses, air raid wardens, pilots, drivers and mechanics. She was desperate to be part of the action herself, but it wasn’t until the Americans entered the war in 1944 that she was able to go into Europe and begin covering the war for American Vogue.

Women weren’t allowed at the front, so she travelled across the continent photographing bombs exploding in Saint Malo, a makeshift operating theatre in Normandy, refugees in Luxembourg and Vienna’s bombed out opera house. To accompany the pictures, she wrote impassioned reports on the things she’d witnessed.

She followed the allied troops as they made inroads into Germany, photographing Nazis who’d committed suicide rather than face capture. Nothing prepared her, though, for what she encountered on entering the concentration camps at Buchenwald and Dachau shortly after their liberation. The exhibition shies away from showing her most harrowing pictures of emaciated bodies or the ovens used to burn the corpses. It feels like a cop-out, as does their refusal to allow us to reproduce any of her war pictures; it also robs her career (and the exhibition) of its climax. On show, though, is the photograph for which she is most famous – taking a bath in Hitler’s tub, trying to wash away memories of the horrors that he perpetrated and which would haunt her for the rest of her life.

After the war she returned to England, married and had a son with Penrose, retired to the country, took up gourmet cooking and put her camera away except to photograph artist friends. These photographs are fun, innovative and beautiful; Saul Steinberg grapples with a recalcitrant hosepipe, Henry Moore hugs one of his sculptures as if his life depends on it, while Jean Dubuffet and Georges Limbour press their hands against a window like a couple of naughty schoolboys. Inevitably, though, they feel like a coda to the main event.

Does the exhibition bring Lee Miller and her remarkable career into sharper focus, then? Not really. Scale is one problem. Many of the prints are tiny, and peering at row after row of small images is tiring and soporific. One needs an occasional change of pace, and a few enlargements would have alleviated the problem. Other prints are lacking in contrast and clarity; the rich tonality of her 1941 photo of Elizabeth Cowell wearing a Digby Morton suit (pictured above), for instance, came to light only when I saw it on screen.

In my view, emphasising her role as an artist and labelling her a Surrealist while glossing over her war reportage – which was so singular and so important – does her an injustice. Technically and creatively, she was innovative in every way. Her special skill, though, was the ability to respond to the needs of the moment. Whether taking superb fashion shots, exploring the creative potential of her medium or documenting monstrous war crimes, she was able to adapt her approach in a way that few people are capable of.

Ironically, this may be the very reason she slips from your grasp when you try to pin her down and categorise her as a fashion photographer, an artist or a war reporter. She was so much more than any of these. She is plural.

- Lee Miller at Tate Britain until 15 February 2026

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment