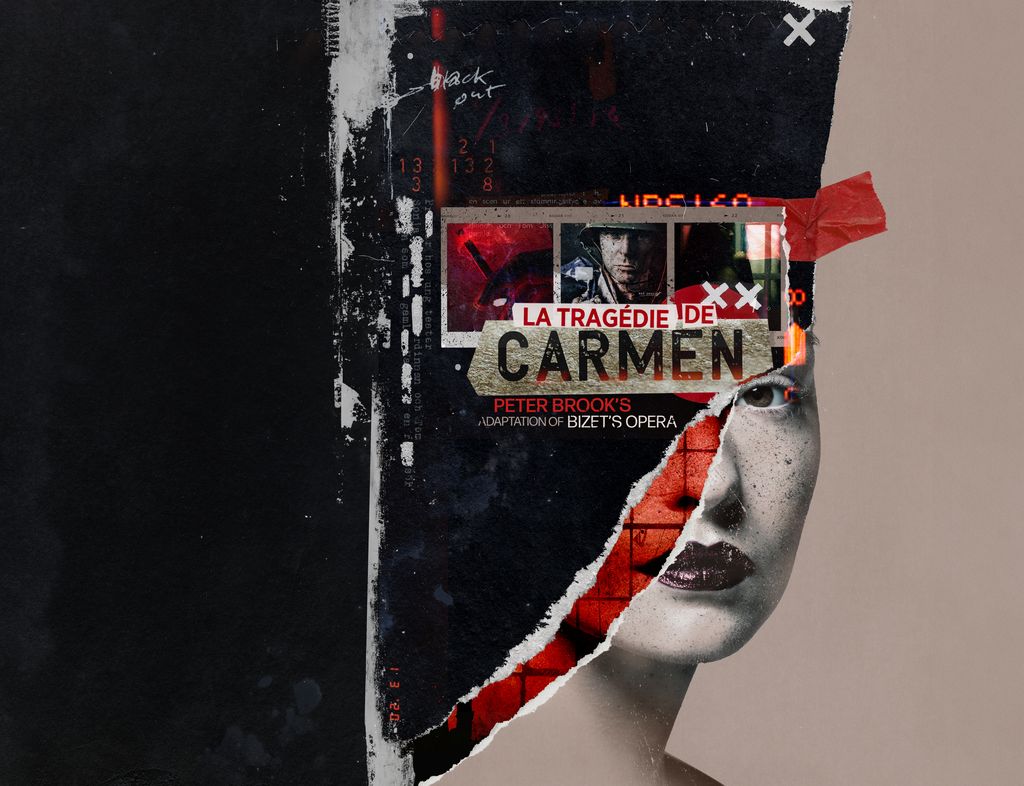

Peter Brook's reimagining of Bizet's Carmen condenses the scale of the original into a more intimate theatrical experience. The score has been starkly cut, the orchestra reduced, and only four singing roles remain: Carmen, Don José, Escamillo and Micaëla. There are also three speaking roles: Zuniga, Lillas Pastia and Garcia (Carmen's husband). In Bizet's opera, Lillas Pastia is only briefly portrayed, and Brook incorporates Garcia, who does not appear in the opera, from the original story – Merimée's novella Carmen.

As Brook uses Bizet's music, it is only natural to think of the original Carmen and to compare the two. However, Brook’s La Tragédie de Carmen is distinct in that it is a close-up of the four main characters and gives us the opportunity to explore the character’s behaviour. It is specifically Carmen’s behaviour and the reasons that ultimately lead to a femicide that our production focuses on. As opposed to some other productions of Carmen, our production employs Brechtian techniques and deliberate stereotyping to demonstrate how Carmen's position in society, viewed through the pervasive male gaze, compels her to adjust her behaviour as a form of survival instinct. These devices serve to highlight the theatrical construct and to make it clear that this is not a world to get lost in – it is a production designed to spark critical thinking.

Using these devices, we actively subvert the typical "femme fatale" narrative that is usually associated with this character. We have added an "active narrator", who in his capacity as an almost ‘master of ceremonies’, observes and initiates action on stage, moves between the roles of a commentator and characters, and ultimately serves as the embodiment of our investigation of the "femme fatale" stereotype (pictured below by Genevieve Girling, Cameron Cook and Niamh O'Sullivan).  The concept of the "femme fatale" is one that, in our opinion, has not been the subject of much debate and analysis. The origins of this overly sexualised ideal can be traced back to 19th century French literature, but has also been present throughout history, from Circe in Homer's Odyssey to Eve from the Bible. Carmen is frequently depicted as the quintessential "femme fatale"– a "temptress", "seductress" and "siren" bent on causing chaos and ruining virtuous men. Merimée's novella Carmen can be categorised into a genre of 18th- and 19th-century French literature that could be described as "cautionary tales for promising young men"'. Another prominent work in this vein is Prevost’s Manon Lescaut. In both, once hopeful young men now in ruins recount their ordeals with a "femme fatale". The protagonists’ survival is intricately linked to the seductresses' downfall. The depicted life that is "lost" is that of the young man, despite it being the woman who forcibly meets her end. These narratives disguise themes of violence against women by presenting them as tales of young men’s redemption through an act of self-defence. Consequently, the responsibility for the murder is shifted onto the female victim, depicted as being at fault for not reciprocating affection as expected.

The concept of the "femme fatale" is one that, in our opinion, has not been the subject of much debate and analysis. The origins of this overly sexualised ideal can be traced back to 19th century French literature, but has also been present throughout history, from Circe in Homer's Odyssey to Eve from the Bible. Carmen is frequently depicted as the quintessential "femme fatale"– a "temptress", "seductress" and "siren" bent on causing chaos and ruining virtuous men. Merimée's novella Carmen can be categorised into a genre of 18th- and 19th-century French literature that could be described as "cautionary tales for promising young men"'. Another prominent work in this vein is Prevost’s Manon Lescaut. In both, once hopeful young men now in ruins recount their ordeals with a "femme fatale". The protagonists’ survival is intricately linked to the seductresses' downfall. The depicted life that is "lost" is that of the young man, despite it being the woman who forcibly meets her end. These narratives disguise themes of violence against women by presenting them as tales of young men’s redemption through an act of self-defence. Consequently, the responsibility for the murder is shifted onto the female victim, depicted as being at fault for not reciprocating affection as expected.

Notably, before José murders Carmen in Mérimée’s novella, he explains to her that her death is her own fault. He literally tells her, “c’est toi qui m’as perdu” (“it is you who has ruined me”). It is José’s fixation on Carmen and the choices he makes as a result of this obsession that ultimately lead to his downfall. Carmen is far more complex than a mere wild woman without depth; her story is darker and richer.  The characters encountered by the audience are not the typical or familiar representations that they might be used to. Carmen is a young woman of a lower social status, striving to survive in a male-dominated society. She employs various tactics to navigate tricky situations, through which our production aims to demonstrate how the pressures of her societal status and specifically the male gaze influence her. Each male character she encounters stereotypes her according to her gender, background and position in society. Her costumes consist of various female stereotypes throughout history, our intention being to highlight the repetitive nature, ridiculousness and sometimes dangerous implications of these "ideals".

The characters encountered by the audience are not the typical or familiar representations that they might be used to. Carmen is a young woman of a lower social status, striving to survive in a male-dominated society. She employs various tactics to navigate tricky situations, through which our production aims to demonstrate how the pressures of her societal status and specifically the male gaze influence her. Each male character she encounters stereotypes her according to her gender, background and position in society. Her costumes consist of various female stereotypes throughout history, our intention being to highlight the repetitive nature, ridiculousness and sometimes dangerous implications of these "ideals".

Brook expands upon the backstory of Don José, as detailed in Merimée's novella. After having been exiled from his hometown following a violent altercation, Don José relocated to Seville, yet continues to struggle with the consequences of his actions. He experiences a sense of helplessness in his inability to manage his impulsive aggression, and instead, tends to blame others, particularly Carmen, for his violent behaviour. In the course of the production, he is convinced that he is unable to escape his "evil" ways and that Carmen is the main reason he has ultimately ended up on this dark path of life. He believes she owes him her love and cannot bear her refusal of the affection he expects from her (pictured below by Genevieve Girling, Elgan Llŷr Thomas and Niamh O'Sullivan). Escamillo presents himself as the audience may be used to seeing him; a very strong, masculine, proud and cocky man. He derives pleasure from the attention that fame brings him, but in this interpretation, he feels uncomfortable in the role of the strong male stereotype. He experiences doubts and fears and is unable to sustain his confident, macho performance. This is in fact, what ultimately draws Carmen to Escamillo in our production.

Escamillo presents himself as the audience may be used to seeing him; a very strong, masculine, proud and cocky man. He derives pleasure from the attention that fame brings him, but in this interpretation, he feels uncomfortable in the role of the strong male stereotype. He experiences doubts and fears and is unable to sustain his confident, macho performance. This is in fact, what ultimately draws Carmen to Escamillo in our production.

Micaëla, who is often depicted as unlikable, stuck up and overly religious, is shown as young woman from a small town who is overwhelmed by and unprepared for the reality of what expects her in Seville. She is naturally threatened by and afraid of Carmen, but most importantly, she is also in awe of her. Carmen is a woman who appears to live freely and who thrives and seems comfortable in her sexuality – something Micaëla has never been allowed to explore. Her frustrations towards Carmen stem mainly from this, not from Carmen "stealing" Don José from her.

Our concept may be bold, but the underlying message regarding the danger in female stereotyping is one that unfortunately persists in our societies (i.e. recent studies highlighting an increase in domestic abuse during major football games, various “incel” shootings, the growing “trad-wife” trend, continuous femicides and female disappearances, etc.). Our objective is to offer an alternative interpretation of Carmen, encouraging the audience to consider her actions from a new and different perspective and to recognise the patterns that ultimately lead to her death.

- Further performances of La Tragédie de Carmen at the Buxton International Festival on 9, 13 and 16 July

- Robert Beale will be covering all productions at the festival on theartsdesk

- More opera reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment