The Marriage of Figaro, Welsh National Opera review - no concessions and no holds barred | reviews, news & interviews

The Marriage of Figaro, Welsh National Opera review - no concessions and no holds barred

The Marriage of Figaro, Welsh National Opera review - no concessions and no holds barred

Compelling revival, punches, placards and all

Drained as they are at present of crucial funds, WNO are managing to put on only two operas this spring, and spaced out to the point where it could hardly be called a season. For their new Peter Grimes we must wait till April. Meanwhile we can relish Tobias Richter’s sparkling nine-year-old Figaro, skilfully revived, with a few tweaks, by Max Hoehn.

Whatever the pressures, there is not the slightest diminution of standards. I missed the pre-pandemic revival. But Hoehn has now cut out the overture stage business (no great loss), and the opera is sung in its original Italian, which for my money is an improvement. But the stylish core of the original remains. Sue Blane’s elegant contemporary period costumes counterpoint subtly with Ralph Koltai’s clever, vaguely realist, vaguely abstract rolling screens, which provide just enough context while above all leaving space for the intricate movement of character and dance that is the work’s essence.

From the start, Richter pulled no punches over the inherent violence of this only superficially buffo opera, and the revival throws a few of its own. In the red corner welcome Michael Mofidian’s brilliant, uninhibited Figaro. His execration of women in his finale aria, da Ponte’s equivalent of Beaumarchais’s diatribe against the whole race of aristocrats, is delivered with such superb bravura that he may expect a visit from the non-crime hate police. In the blue corner, Giorgio Caoduro’s Almaviva, railing against his servant’s success with the woman he desires, is not less venomous, only marginally less frightening.

They are a fierce, compelling match which sometimes overpowers the women they variously do or don’t crave. Christina Gansch’s Susanna is at her best in the (false) refinement of “Deh vieni!”, in exquisite contrast with Figaro’s philippic, just ended. But if her voice elsewhere sometimes lacks the last degree of sensuous warmth, she more than compensates with a beguiling stage presence and, I regret to add, a violent streak of her own, delivering a right hook to Figaro’s jaw when she catches him embracing Marcellina, and a good thump in the crutch when he plays up to her pretences in the last act. Such is charm betrayed.

They are a fierce, compelling match which sometimes overpowers the women they variously do or don’t crave. Christina Gansch’s Susanna is at her best in the (false) refinement of “Deh vieni!”, in exquisite contrast with Figaro’s philippic, just ended. But if her voice elsewhere sometimes lacks the last degree of sensuous warmth, she more than compensates with a beguiling stage presence and, I regret to add, a violent streak of her own, delivering a right hook to Figaro’s jaw when she catches him embracing Marcellina, and a good thump in the crutch when he plays up to her pretences in the last act. Such is charm betrayed.

Chen Reiss’s Countess (pictured above with Harriet Eyley as Cherubino) is a more genuine portrait of wronged – because genuinely wronged – womanhood, aggravated by the fact that her quarterings are less secure than her husband’s (remember, she started life as ward of middle-class Dr. Bartolo). How much of this can be read into Mozart/da Ponte is debatable. But Reiss nicely combines aristocratic dignity and a playful susceptibility (including to Cherubino when he/she somehow lands on her knee in Act 2). Her arias are finely sung: “Porgi amor” to perfection, “Dove sono” with a slightly dry quality of tone that mildly, only mildly, disappoints.

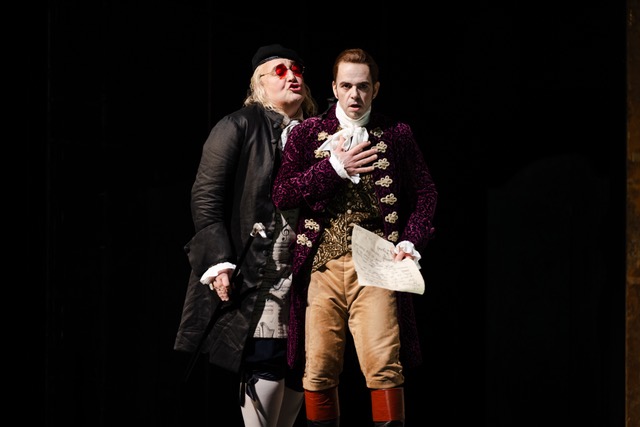

The Cherubino is Harriet Eyley, admirably athletic and tremulous in “Non so più”, but a soprano rather than mezzo Cherubino, without the dark colourings that can intensify the disturbing (and disturbed) aspect of this adolescent boy-girl. But these three sopranos duet and trio beautifully together, only tending to retreat somewhat in combination with their powerful menfolk. In support Monika Sawa is an expertly bitchy Marcellina, spitting vitriol in her scene with Susanna, alas deprived of her last act aria; Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts (pictured above with Giorgio Caoduro as Almaviva) finds two types of sliminess in Basilio (also sadly senza aria) and the lawyer Curzio. Wyn Pencarreg makes the most of Bartolo’s revenge aria, another black moment in this masterpiece of miscreance, and Eiry Price impresses as Barbarina, no mean feat in the very few minutes Mozart vouchsafes her – alone, it’s true, and downstage.

The Cherubino is Harriet Eyley, admirably athletic and tremulous in “Non so più”, but a soprano rather than mezzo Cherubino, without the dark colourings that can intensify the disturbing (and disturbed) aspect of this adolescent boy-girl. But these three sopranos duet and trio beautifully together, only tending to retreat somewhat in combination with their powerful menfolk. In support Monika Sawa is an expertly bitchy Marcellina, spitting vitriol in her scene with Susanna, alas deprived of her last act aria; Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts (pictured above with Giorgio Caoduro as Almaviva) finds two types of sliminess in Basilio (also sadly senza aria) and the lawyer Curzio. Wyn Pencarreg makes the most of Bartolo’s revenge aria, another black moment in this masterpiece of miscreance, and Eiry Price impresses as Barbarina, no mean feat in the very few minutes Mozart vouchsafes her – alone, it’s true, and downstage.

Under Kerem Hasan the whole performance whizzes along, occasionally a touch out of breath, mostly with exhilarating vitality. His style, too, is punchy. The wind chords in the overture already show his colours, and on odd occasions his energy overrides the needs of the singers. But this will settle down. The chorus are on their usual top form, singing like angels, and loving the opportunity for some individual touches of picaresque comedy. For the curtain calls they parade placards: “Save Our WNO”. And so say all of us.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

The Marriage of Figaro, Welsh National Opera review - no concessions and no holds barred

Compelling revival, punches, placards and all

The Marriage of Figaro, Welsh National Opera review - no concessions and no holds barred

Compelling revival, punches, placards and all

The Marriage of Figaro, English National Opera review - long on laughs, short on kerb appeal

Laugh-out-loud funny revival of an ingenious staging

The Marriage of Figaro, English National Opera review - long on laughs, short on kerb appeal

Laugh-out-loud funny revival of an ingenious staging

The Flying Dutchman, Opera North review - a director’s take on Wagner

Annabel Arden offers the Great Disruptor as archetype of the stateless and voiceless

The Flying Dutchman, Opera North review - a director’s take on Wagner

Annabel Arden offers the Great Disruptor as archetype of the stateless and voiceless

Love Life, Opera North review - Lerner and Weill's blast into the past

Time-travelling tale of love and despair - the first 'concept musical' revived

Love Life, Opera North review - Lerner and Weill's blast into the past

Time-travelling tale of love and despair - the first 'concept musical' revived

Jenůfa, Royal Opera review - electrifying details undermined by dead space

Knife-edge conducting and singing, but non-realistic production is weaker in revival

Jenůfa, Royal Opera review - electrifying details undermined by dead space

Knife-edge conducting and singing, but non-realistic production is weaker in revival

Best of 2024: Opera

Comedy takes gold over a year rich in standout performance

Best of 2024: Opera

Comedy takes gold over a year rich in standout performance

La rondine, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - sumptuous orchestral playing in an underrated score

Puccini's 100th anniversary celebrated in style

La rondine, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - sumptuous orchestral playing in an underrated score

Puccini's 100th anniversary celebrated in style

L’étoile, RNCM, Manchester review - lavish and cheerful absurdity

Teamwork to the fore in a multi-credit operatic comedy

L’étoile, RNCM, Manchester review - lavish and cheerful absurdity

Teamwork to the fore in a multi-credit operatic comedy

The Pirates of Penzance, English National Opera review - fresh energy in clear-sighted G&S

Tenor lead shines, and conductor finds new beauties in Sullivan's score

The Pirates of Penzance, English National Opera review - fresh energy in clear-sighted G&S

Tenor lead shines, and conductor finds new beauties in Sullivan's score

Rigoletto, Irish National Opera / Murrihy, Collins, NCH Dublin review - greatness everywhere

Sheer perfection in Soraya Mafi’s Gilda and an Irish mezzo’s Berlioz

Rigoletto, Irish National Opera / Murrihy, Collins, NCH Dublin review - greatness everywhere

Sheer perfection in Soraya Mafi’s Gilda and an Irish mezzo’s Berlioz

The Elixir of Love, English National Opera review - a tale of two halves

Flat first act, livelier second, singers not always helped by conductor and director

The Elixir of Love, English National Opera review - a tale of two halves

Flat first act, livelier second, singers not always helped by conductor and director

Comments

I'm possibky biased as I am

I'm possibly biased as I am Harriet Eyley's manager, but it is good to see a soprano cast as Cherubino. The role was written for soprano, as clarified in William Mann's Magnum Opus on Mozart's operas, and the tessitura works much better. I grew up listening to Suzanne Danco singing the role on Kleiber's recording, and recordings by Sena Jurinac and Edith Mathis, as well as, more recently, Christine Schäfer, prove the musical value equally well.