Yesterday afternoon, Semyon Bychkov's recording of Lohengrin won BBC Music Magazine's prestigious disc of the year. Last year, The Sunday Telegraph named his recording of Eugene Onegin one of the top 10 opera recordings of all time. Proof - if proof were needed - that the Russian conductor is one of the living greats of the operatic pit. His upcoming Tannhäuser next season at Covent Garden is awaited with bated breath. His concert performances with the WDR Symphony Orchestra, Cologne, which he has headed up as chief conductor for the past 12 years, have not gone unnoticed either. None of it should surprise. Karajan spotted Bychkov more than two decades ago. He gave him permission to tour with the Berlin Philharmonic (the first outsider to do so since Furtwängler) and tipped him as a potential successor.

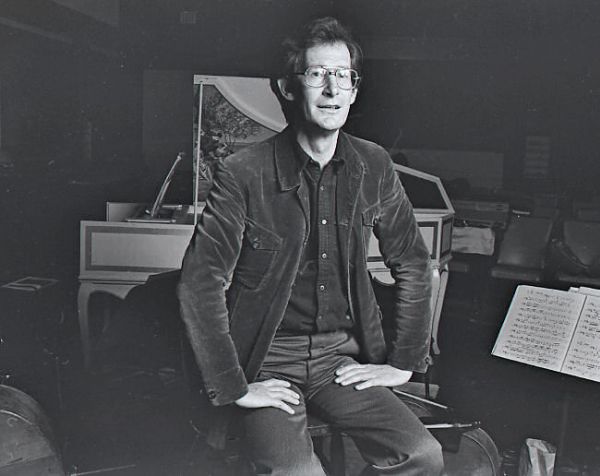

One of the unique things about his award-winning Lohengrin is that it is complete. Previous recordings had always cut various choral chunks and bits of recitative. This disc is, therefore, also a thoroughly pleasing restoration job. I therefore begin by asking him about the great restorer of our age, Sir John Eliot Gardiner (pictured right)...

IGOR TORONYI-LALIC: What do you think of Gardiner's way with music?

IGOR TORONYI-LALIC: What do you think of Gardiner's way with music?

SEMYON BYCHKOV: I adore it. I absolutely adore it. I admire this man no end. He has a vision of music and he has the courage to stick with this vision over his lifetime. We shouldn't forget that, until not such a long time ago, those of us from - I don't know the right words for this - this kind of a traditional aesthetic, used to consider those who work with early music and period instruments as charlatans, which was very hurtful and unbelievably false. It showed a huge, huge lack of understanding and a lack of breadth of vision. Today people like John Eliot, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Giovanni Antonini, and many others, have proved that we have to be multilingual; that we have to be polyglots in music. We can't play all music in the same way. It's beautiful to see someone who shows a way to this music that suddenly makes it fresh. If you listen to Gardiner conducting Schumann's symphonies, you will never say: "Ah, Schumann. A magnificent composer of piano music that is really written for orchestra and orchestral music that sounds like it is written for piano." You never think that with John Eliot.

There's a similar spirit in what you did with your recording of Lohengrin. You went back to the original texts, the original score, and added all the various cuts that have been excised.

Yes, but that is a musicological decision which I already believed in anyway. It doesn't require any courage.

Really?

No - why should I need courage? I did not compose Lohengrin. Wagner did. I was fortunate enough to have Johan Botha, who sang without any compromises from the beginning to end, not only in the recording but also in the live performances [in Spain and Vienna]. I was fortunate to have a colleague like that. Whereas this other subject that we were talking about is something else. That requires the actual vision of what music is supposed to sound like and how it communicates. Do you want to speak Stravinsky in Wagner's language or Wagner in Stravinsky's or Stravinsky in Stravinsky's, Wagner in Wagner's, Beethoven in Beethoven's? This is a very relevant theme for us today because of all the information that is available to us. I listen to Furtwängler conducting Le Damnation de Faust, an old LP, which I was given 20 years ago by a friend. My God, it is practically unlistenable! But you can't criticise it because at that time the world was very disparate. The Germans were immersed in their German culture, the French in the French and the two didn't communicate as much as today. Their listening experience was much more limited than ours today. So it was OK for a German looking at a French piece to look at it through the prism of German eyes, ears, mind and temperament and vice versa. Whereas today it is not acceptable anymore. We have no excuse. We have a lot of information. In a way, we have to train ourselves to speak many different musical languages.

Why didn't you go down a more thoroughly period performance route for Lohengrin, period instruments etc?

Why didn't you go down a more thoroughly period performance route for Lohengrin, period instruments etc?

That is an accident of history. It just has not been realised. It's pretty funny. In the very beginning when I arrived in Cologne the first really big project that I started [with the WDR Symphony Orchestra, pictured right] was a Beethoven cycle. The orchestra could have had period bows for the strings - the money was available - but the players didn't want it. It's amazing. Later on, when they wanted to - because the generations had changed - the money didn't exist. It tells you something. The orchestra that I inherited was a very traditional German orchestra that imagined Beethoven as something that we describe, with humour, "molto espressivo and molto vibrato". I remember reading through Eroica in the very first rehearsal as chief conductor. They played their Eroica and I played my Eroica. So I kept thinking, how am I going to start - where am I going to start? When we were done, I talked for an hour- and-a-half. I have never spoken so long in my entire life to any orchestra. I said that they will never hear me talk again. Eventually I had to explain the parameters. So, these are the parameters and this is how I would like you to play this music today and if tomorrow another colleague will come and this person will want to do it in a very different aesthetic we ought to be able to do it in that way too. It means that we must have this ability to be a chameleon and become someone else depending on what is required at that moment.

After the break we started playing again and it was very difficult because the way of phrasing, the way of thinking, the way of thinking of the rhetoric of music, the articulation of it, was completely different to what they had always known. If somebody sees a crotchet, the education is to sustain that crotchet till it never ends. Well, sometimes that's right; sometimes it isn't. But it takes a long time until new reflexes are born. Then you have two sets of reflexes which is fine so you produce the one that you need at any given moment. It is a question of educating the orchestra. On the question of gut strings it's just a matter of organisation. I am completely fascinated by all of that. The only thing I do know is that I have heard many performances with guts strings etc. that were not convincing and I have heard tremendous performances - for example the Harnoncourt Beethoven cycle with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe - and they were playing on contemporary instruments and they were amazing. We should be quite clear in our minds that instruments are simply a means of expression. They do not replace expression. They will influence it, help it, sometimes they can hinder it a little bit, but they are not a substitute for expression. And if the expression is convincing you can do it convincingly on modern instruments. If it is not, period instruments won't help.

And judging by your Lohengrin, would it be right to say that you find the historical practice of cutting operas wrong?

And judging by your Lohengrin, would it be right to say that you find the historical practice of cutting operas wrong?

[Laughing] No! It just depends what you cut and who you cut. It's not as simple as a circumcision. If we are faced with gigantic creators - Wagner being one of them - do you think that any one of us has the gift to be able to improve what he has done? The answer is, no. Strauss is another one. You know those cuts in Rosenkavalier? It's very interesting. They have been there forever. Well, there is a letter from Strauss to the man who conducted the premiere in Dresden (Ernst von Schuch, pictured left). Strauss complains bitterly about those cuts. The conductor was one of those tailors - there were plenty of those at that time. He loved to cut music. But it was a very different atmosphere at that time. All of this was new music. And let's face it: you get a new score, you haven't lived with it, you're not yet sure about its pacing, all you see is that it's pretty goddamn long! Rosenkavalier is a longer opera than one dares to think!

As is Lohengrin.

As is Lohengrin! But we don't take into consideration today two things that happened when Lohengrin was first performed. First, they had difficulty finding a tenor able to sing music like that; nothing like that had ever been required of a singer. Secondly, Liszt conducted the premiere in Wiemar using tempi that took much, much longer than Wagner ever imagined. Wagner understood why and he wrote to Liszt a letter. It was about the recitative. The contemporary practice in the German operatic scene was that, during the recitatives, singers did essentially what they wanted. The conductor did not have the opportunity to lead the singers during the recitative. He had to follow. The mistake is when this is not addressed in rehearsals. Wagner formulated it very clearly: "In recitative," he says, "I have already thought about the pace at which I would like the text to be spoken." So the rhythm of the speech is in the music. The character of that rhythm dictates the tempo in which it will be sung. That does not mean that, because it is a recitative, that it is a free tempo. But it does immediately give you an idea of what tempo we want. So if people like Strauss, Wagner, Mozart or Verdi are involved, I see no reason why we have to adjust the pieces. We are not improving them by adjusting them.

I agree with you to some extent, but let me play devil's advocate for one moment. Isn't it wrong of us - somehow inversely arrogant - to think that our age is less able to match the successes of the past? This is the only age that thinks that we are unable to tweak historic works. Mahler fiddled with Beethoven, Mendelssohn with Bach and so on. Why are we so arrogant to think our age is definitively less able to fiddle with that which previous ages have thrown up?

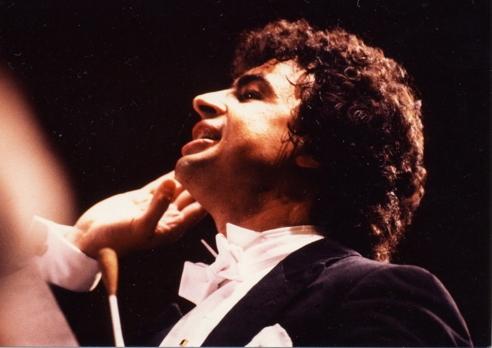

Because we have a hell of a lot more information about these pieces than they did. There were no recordings at that time. Karajan had to travel on a bicycle to Salzburg to hear Toscanini (pictured left) conduct Missa Solemnis. How many opportunities would these people have had in their entire lives to hear a piece done in a most extraordinary way, for example, Toscanini's way, for someone in his twenties? Today, that is not the case at all. But what Mahler did to Beethoven is not what I have threatened many times to do myself in order to make Eroica new. Which is to move the Marche funèbre to the last movement. I do it in jest, when I see certain productions by stage directors that are not particularly respectful of the authors that have created these amazing masterpieces because they like to present something new which will make it contemporary and worthwhile to us. Well, just because we are doing it means it is worthwhile! Otherwise we would not be bothering. So, just because I would change the movements of the Eroica you could say that it is absolutely okay because all the notes of Beethoven are still there. Except the whole meaning of the piece has changed and I have no right to do that. Mahler did not do that kind of thing. He worked with orchestration. Beethoven, after all, was not able to hear his own music. At that time it was not sounding clear. Mahler wanted to bring a certain clarity and reinforce voices that were not coming through, stuff like that. It was with the best intentions. So it is not quite the same as introducing cuts that will distort the form of these works and the form that we can only admire.

Because we have a hell of a lot more information about these pieces than they did. There were no recordings at that time. Karajan had to travel on a bicycle to Salzburg to hear Toscanini (pictured left) conduct Missa Solemnis. How many opportunities would these people have had in their entire lives to hear a piece done in a most extraordinary way, for example, Toscanini's way, for someone in his twenties? Today, that is not the case at all. But what Mahler did to Beethoven is not what I have threatened many times to do myself in order to make Eroica new. Which is to move the Marche funèbre to the last movement. I do it in jest, when I see certain productions by stage directors that are not particularly respectful of the authors that have created these amazing masterpieces because they like to present something new which will make it contemporary and worthwhile to us. Well, just because we are doing it means it is worthwhile! Otherwise we would not be bothering. So, just because I would change the movements of the Eroica you could say that it is absolutely okay because all the notes of Beethoven are still there. Except the whole meaning of the piece has changed and I have no right to do that. Mahler did not do that kind of thing. He worked with orchestration. Beethoven, after all, was not able to hear his own music. At that time it was not sounding clear. Mahler wanted to bring a certain clarity and reinforce voices that were not coming through, stuff like that. It was with the best intentions. So it is not quite the same as introducing cuts that will distort the form of these works and the form that we can only admire.

It's like building a house. You are building it. It is in the process of construction. Someone designed it etc. You walk in on site and you observe it. You don't quite know yet the proportions between the various rooms and walls and ceilings. You don't know what the interior decoration will be like. You say: "Let's change this wall and bring it a little bit closer to the other one". You start doing that. Maybe you will be right. Very often you will be wrong. Because you don't have the vision of the complete thing that the person who has created it, the architect, has. When the building is finished, then you have the chance to look at it and live in it. Then you will have a much better opinion whether it works in terms of form and structure and whether the interior decoration is organic and corresponds to the structure of the piece and vice versa. Those people working with what was essentially new music didn't have the luxuries that we have today. They had the right to do it; we don't.

Are you one of these conductors that would politely back out of a production that wasn't respectful to the original composition?

I have never done that. I have never left a project. I have been tempted on many occasions. And on two of them, I was more than tempted; I was absolutely on the verge. There were always two reasons why I didn't. One: I would say to myself, I can leave but then those colleagues of mine that are singing this will have to live with it. They cannot afford to go. They will get a reputation for being a troublemaker. It is their job to follow the vision of the stage and conductor and they just have to obey and if they make trouble they are jeopardising their whole career. They have to stay and I am abandoning them. Reason two: why should I be the one to go?

But that's the nature of productions these days, isn't it? Stage directors increasingly run the joint now.

That's not completely true. It is partly true. It's not true everywhere, all of the time. If you arrive and the production is essentially done, you may not like it but it is too late to complain. If you are present from the beginning, you have more of an opportunity to influence it. But that's a sticky point. You may have the opportunity but you're not guaranteed the result. Because in the end you are not doing the mis en scène. It's like constructing a building. Until everything is in place, which is when people will actually see and hear a piece, you don't quite know how it will turn out. So often the initial presentation of the concept and the end result that the public receives have little in common.

One felt that same disjuncture with this Lohengrin. For some critics Lohengrin is a problematic opera at the best of times. And you were adding music, making it longer, potentially more unwieldy and even less dramatic. But, in fact, it worked. And so brilliantly. Were you ever afraid of putting back the cuts?

No, because I trust the music that I conduct. If I don't trust it, I don't have a right to conduct it. The reason that I am conducting this music - whatever it is - is because I cannot live without it otherwise I wouldn't be doing it. There is so much extraordinary music: enough for many lifetimes. You cannot realise everything you love, so at least what you do you should love. It is composed by Wagner. It is tremendous stuff. There is a reason why it should be there. The cuts tell us certain things about Lohengrin that we wouldn't have found out: where he comes from and therefore why he is here. The primary person we do every project for is not us; it is for the creator. If you don't believe in the creator, find another one. But if you do it, you believe in the creator, serve the creator, don't use him, don't use the piece. It is a very simple and most basic job description of an interpreter: don't be a user, be a server. You can find tremendous fulfillment in serving someone that you admire. It makes you grow, having contact with a great masterpiece and it is as simple as that. There is nothing else. Musicians have this ingrained through education. The way of musical behaviour we receive from our teachers. All musicians from the very beginning, when they start playing the fiddle or flute, the score is being pointed out and you have to imagine what's behind the notes and carry it out faithfully and to the best of your ability. Every single person studying music receives that kind of attitude. It should be true to all interpreters not only musicians.

I can agree with that to some extent. But there are certain pieces that should be upturned. I don't mind conductors or directors doing that. Rupert Goold's Turandot at the English National Opera (pictured left) was brilliant in this way. It subverted what is fundamentally in my view a pretty nasty work.

I can agree with that to some extent. But there are certain pieces that should be upturned. I don't mind conductors or directors doing that. Rupert Goold's Turandot at the English National Opera (pictured left) was brilliant in this way. It subverted what is fundamentally in my view a pretty nasty work.

I'm not saying that serving a creator and the work which is being given to us is being subservient. Just because you realise every fortepiano and every diminuendo exactly as you see it in the score is not a guarantee of a great performance. That has nothing to do with it. It is all to do with the spirit of the performance. That is why if you have a production of an opera where the subject is being extrapolated from the time it is conceived and put on the moon, for me, it is not the subject that will be decisive but the way I feel towards it. It will be either consequent, consistent with the spirit of the work, or it will not be consequent. There will be a price to pay for the changes or there won't. It has to retain the sense of the integrity of the piece; the spirit of the piece has to be authentic. As long as that is preserved, whatever one does with the work is their own business. Stravinsky, who hated "interpretation", conducted his Sacre at different times of his life with very different tempi. It has nothing to do with any kind of a rigid ideological position to anything new or different. The reason we do these great pieces is because they give us an opportunity to discover something in them. And you can do that without using them; you can do that simply by growing with them.

I will quote something Wagner wrote because it is so unbelievably actuel. People who hear it are pretty astonished because we always want to think that these issues are of our time. It is not quite like that. "There is scarcely an opera producer alive who has not taken it into his head at some time or another to stage Don Giovanni in a contemporary setting, whereas every intelligent person should be telling himself that it is not this work which should be tailored to suit our times but we ourselves who must adapt to the times of Don Giovanni if we are to find ourselves in harmony with Mozart's creation." That's from 1878. The question was already posed. And he was a creator. He was not an ideologue. He was not only able to speak about things. He was the one who said, "Kinder macht neu". You can and will find new stuff in doing the same bloody masterpieces, by being just obsessed by them because the pieces are what they are. They don't change; we change, as we go through life. That's why we have no right to change them. We only have to find ourselves in harmony with them. Does that make sense?

Yes, that makes sense. I want to go to one or two specifics of your Lohengrin interpretation and what you say to orchestras to get them to do what they do. To pick up on one thing: transition. The way you make the dynamic markings work, moving from Ortrud [Petra Lang, pictured right, in the 2009 Royal Opera House production, also conducted by Bychkov] to Elsa [Adrianne Pieczonka], for example, in Act Two, the orchestra has to exude such bitterness one moment then be as pure as heaven, and you do it quite magically. Do you do that in takes?

Yes, that makes sense. I want to go to one or two specifics of your Lohengrin interpretation and what you say to orchestras to get them to do what they do. To pick up on one thing: transition. The way you make the dynamic markings work, moving from Ortrud [Petra Lang, pictured right, in the 2009 Royal Opera House production, also conducted by Bychkov] to Elsa [Adrianne Pieczonka], for example, in Act Two, the orchestra has to exude such bitterness one moment then be as pure as heaven, and you do it quite magically. Do you do that in takes?

No, it is in the piece. Actually, it's quite simple. I am in the pit, so is the orchesta, the singers are on stage. At this moment, I am with Ortrud, I have to be her at that moment, which means a complete identification with this person in front of me. After this, it moves from Ortrud to Elsa. At that point I become Elsa. And so it is completely schizophrenic. But with Wagner you have the luxury to do this because once they open their mouths they keep it open for a while before another one gets his chance. With others you get no chance like that. In Strauss, it's a subconscious thing. In Lohengrin it is a complete identification with the characters on stage and fusion with the artists who incarnate those characters which allows you to go from skin to skin to skin to skin. The orchestra has to know exactly the same, just as they have to know what everybody else is playing. It is a question of chamber music, but chamber music not for four people but for 120; the difference is only in numbers. The principle is exactly the same. Like the objects on this table [grabs a salt shaker]. Every object on stage has to have space for expression. This is human society. It always has to be shaped otherwise it becomes monotonous. It has to be all the time in transition. What is Wagner but transition. One thing is being borne out of the predecessor and gives birth to the next thing. It has to do with tempo; it has to do with the dynamics and it has to do with timbre.

There is one miraculous thing at the beginning of Lohengrin. We hear a major chord from the violins: two violin groups divided into four voices. It's in A major. Several seconds later they are joined by woodwinds playing exactly the same chord. The violins sneak into it so that you don't really hear when the sound was born. Like the story itself, it has no beginning, it has already been going on, like life, we become aware of it but not at the time that it was born. When the woodwinds join the strings in exactly the same A major chord, the last thing we should hear is, ah, here comes the woodwind colour, it should be imperceptible so that the string colour is being transformed into a new colour because it is being mixed with the woodwinds, which grow through the transformation (not only in volume) and then reduce. It is Wagner's miracle. It is in the score. It is very difficult to do because you deal with woodwind instruments that have to speak at the time when the note has to appear, not like the strings whose notes can appear from nothing, which means you have to create an illusion which means the strings have to create enough crescendo in the preceding seconds before the woodwind enter so that by the time the woodwinds enter it will not be quite so noticeable. So all you notice is a transformation of colour.

This talks of space and transitional relationships makes me think of volleyball, which you used to play a lot: the figures in constant flow, the idea of peaks and troughs of activity etc. Is sport very important to you?

It is vital. For so many reasons, not just physical. It's existential. It teaches you to live. Competition is a by-product of sport. Essentially sport means, when it is played the way it was intended by the ancient Greeks, to surpass ourselves constantly. That is something one has to do all your life. Sport is such a very direct way of doing that. It essentially builds up character.

Conducting is quite a physical, athletic thing and opera is such a team sport. Can you transfer sporting skills to opera?

Of course. It is so similar. When I listen to athletes, particularly athletes in collective sports, when they describe their matches, when Wenger talks about football, he has a very poetic way. He talks about the game as an art form. He is absolutely right. It is an art form of human creativity. Just what these guys do is they do it with a ball and they have an athletic gift but they have to do it with intelligence. One thing that they have to be able to do is they have to anticipate what will get them a result. It is a passing game like chess. One move will create another will create another will result in a goal and this is what you learn when doing sport as a kid. You learn character. You learn not to surrender or give up or accept the idea that the game is not over before whistle is blown or to assume you have won it before the whistle has blown. What is the difference between that and the rest of our lives? The important thing is about space because all of these objects have to have space. Wouldn't it be nice, ideally, for everybody to have space? There's nothing wrong with the idea. But most of the time this will come to a conflict and then someone has to decide who has the priority of attention. This is what happens in music.

Shostakovich was a big football fan too, right?

Shostakovich was a big football fan too, right?

He supported Zenit, the St Petersburg team (pictured left, Shostakovich attending a Zenit game). That's where Arshavin came from when he joined Arsenal.

Did you see Shostakovich about town much?

On many occasions I stayed as close to him as you and I are now, without speaking to him because I was a student. He was very often present in St Petersburg because his music was performed all the time. In the small Philharmonic Hall the artistic director was a great friend of Shostakovich's and an admirer and he was teacher of musical literature in the Glinka School [where Bychkov studied] so we heard a lot about his music. And all the time his chamber music was performed in the hall with him present. I was often standing within a metre of him without daring to speak to him. He had no idea who I was.

He was famous for having a distinctly awkward, nervous aura.

Yes, he was a very nervous person. It is easy to understand for anyone with his notoriety and his history during all those years when he had no idea whether he would see another day as with millions of other people. It was easy to understand the conflicts within this man. In certain situations people would expect from him the kind of civic courage that he was unable to show. For example he joined the Communist Party, his name appeared under the condemnation of Solzhenitsyn, and all the intelligentsia pulled their hair out: "How could he do that? After what they did to everybody and to him?" But who are we to judge someone who lived through what he lived? He didn't destroy anyone. He never killed anybody; he never informed on anybody, which is already a lot more than could be said about a number of more influential people. His mission on this planet was to create what he created and he had to find a way to survive and he did.

You left the Soviet Union in the early in 1970s?

1975.

How did you manage to do it?

I emigrated with the official permission of the government because, being Jewish, I was fortunate to qualify for that wave of Jewish immigration which started in the late 1960s. They had to concede to the West Jewish immigration in order to have Western technology. That is why I always joke that I was traded for a computer. [Laughs.] But it was no iPhone.

You went to Mannes college in New York. Were you at all disappointed with what you found in the West?

No. You can be disappointed by certain facts in life which don't correspond to what you would like to see. If you do not, there's something wrong with you. There is not one person who is happy about every aspect of the planet. I was not disappointed. As I never believed it was perfect, whatever I found was not a disappointment. It was an expectation.

You then became chief conductor in various far-flung towns - at the Grand Rapids Symphony and Buffalo Philharmonic - where one presumes classical music was a pretty foreign thing.

Not true. I tell you something that I discovered when I was appointed to Grand Rapids, which was my first professional orchestra in America. It's in Michigan. I looked at the history of the orchestra. It was 50 years old at the time. Do you know who one of my predecessors was? Nicolai Malko. He was the teacher of Ilya Musin [Bychkov's teacher], so in a peculiar way his musical grandson became his successor, however long removed. No, the whole thing about the States is miraculous. It has to do with the fact that culture is supported privately by people who live with their communities. So if they want to have music they will create an orchestra. They will give money for it. You will go through America and find orchestras in all sorts of little places that you didn't know existed. It may not play many concerts in a year. But it will still exist. And as long as it exists it will play music. As long as it will play music people will come to hear it. And as long as they hear it you can't say they know nothing about music.

What did friends and teachers - people like Ilya Musin (pictured, far right, next to a young Valery Gergiev) - think of you leaving the Soviet Union?

What did friends and teachers - people like Ilya Musin (pictured, far right, next to a young Valery Gergiev) - think of you leaving the Soviet Union?

When the government cancelled my debut with the St Petersburg Philharmonic, one week before I left, he came to the conservatory and said to me: "That's the decision. Now you are free to do what you have to." He blessed me. He was the last person I saw before I flew away early on the morning of 5 March, 1975. On the way to the airport I stopped by his flat to say goodbye to him and his wife.

Was that the last time you saw him?

No. Years later I came back and conducted the St Petersburg Philharmonic and he was there. Finally I came the last time when we were celebrating his 95th birthday. He was conducting as well. He was unbelievable. It's filmed. I was there for several days in 1999. We went to the conservatory; I sat in his class as I had done when I was a student. That day I had rehearsed with the Mariinsky Orchestra for his birthday gala. He turned to his students and said: "You know this pupil of mine", he pointed to me and he proceeded to say things that no money in the world would be enough to receive from someone like him. It's a priceless document. It was one of these miracles you couldn't foresee or script.

Karajan (pictured right) said something extraordinary about you too. He said he wanted you as his successor, is that right?

Karajan (pictured right) said something extraordinary about you too. He said he wanted you as his successor, is that right?

He didn't say that he wanted me. He simply mentioned me. He was very often asked in the last years who he could see as his successor and he mentioned my name. It was quite an extraordinary statement. In fact, I received a letter from Karajan after he died.

How?

When he resigned from Berlin, I was very depressed because I hated to see that relationship go the way it was. I hated to see an old man at the end of his life receiving what he was receiving. In June 1989, several years later, I sat down and wrote him a letter and thanked him for his support. He approved my recording with the orchestra in 1986. He approved my touring with the orchestra the same year - the first time since Furtwangler that someone other than the chief conductor had toured with them in Germany. In that sense he was not a particularly close, or I could not even call it a relationship, he was simply a man who approved of my work and approved of the way I was thinking based on what he heard from me. It meant a great deal to me then because of the role that he played before I had even met him. So I wrote to him and thanked him for that. And I included my recording of Shostakovich Fifth Symphony as a gift because it was the first recording I ever made with his approval. It was June. I heard nothing. I went to Australia. I was in Melbourne getting dressed for a concert and the news came in that he had died. So I went to conduct Shostakovich Eight. It was really, really hard. I put on the TV and I see old video of him conducting Zarathustra. A few days later I am getting dressed again for the concert and I get a call from my secretary in Paris [where Bychkov was the chief conductor of the Orchestre de Paris]. We talked about this and that. "Anything new or interesting?" I asked. There was one letter. It was personal and it said "Salzburger Festspiele". My heart went down. I said, okay, I would like you to fax it down to reception and I will go downstairs in two minutes on the way to the concert and pick it up. It was his answer to my letter. Which was beautiful, very personal, very tender and it was just unbelievable to have that letter several days after he died. He obviously wrote it days before he died.

You also worked with the controversial founder of the talent agency, Columbia Artists Management Inc. (CAMI), Ronald Wilford, who gets a lot of stick from some quarters for the way he handled peoples' careers.

Wilford wasn't the founder. CAMI was founded by Arthur Judson, who was the most influential man in American classical music at his time. Wilford became his successor and became the most influential man in classical music in America for several decades. And a lot of poison came his way because, as with anybody who becomes very influential, he attracted a lot of venom.

Many say that his method of management created very conservative conductors: Previn and Levine, for example.

That is so wrong. They are who they are. You can call it any way you want: conservative or progressive; all those terms we apply to politicians will be applied to conductors too. You can agree or disagree. They are who they are no matter who managed them. They got what they wanted because he helped them to have it. For that reason, to this day, they admire this man. He is truly an extraordinary person. You cannot say that Ronald is a monster and, if only it wasn't for him, these artist would have turned out differently. I don't believe that for one second. I was represented by this man. I know him very well. You wouldn't believe it but he came to hear my concert at the Mannes College of Music because he heard about me on the grapevine. And to this day, if you ask him what I conducted, he will still tell you, Nielsen's Symphony No 3, Sinfonia Espansiva. He's never forgotten. Next day, when he came to the orchestra he was beside himself with excitement. He invited me to come with him. He said he'd like to represent me. "With talent like this," he said - and we're talking 1978, so I was 25 years old - "you're going to be with Boston, Berlin, Philadelphia, Vienna, Chicago etc." I said, "Just a moment, please. Why would I want to go to the Philadelphia Orchestra now and do a Mahler symphony? They already know the solutions to the problems. I don't even know what the problems are." It gave him pause for thought.

Then came an invitation from the Grand Rapids Symphony. He was completely opposed to it because he said, you will typecast yourself as a minor orchestra conductor for the rest of your life. I said, "No, I'm going to go there because this is where I want to have my laboratory. I want to learn repertoire and administration and you are the most capable manager we know and you make sure that I don't get stuck there the rest of my life". I went to Grand Rapids and for many years he had nothing to do with me because he couldn't understand my way of thinking and it was only after the Berlin Philharmonic opened its doors to me and that whole thing happened in Berlin with Karajan that we saw each other again. Ronald said, "You were right and I was wrong. And it was right what you did."

He sounds very magnanimous.

Completely. He simply accepted it. It was not the way he was used to. He was used to dealing at the very highest level and producing the very highest level for his artists. He assumed this is what the artist wanted. Well, in my case, I wanted it but not at that time. And so it was like that.

But wasn't he right in one way: you do have to think long-term about your conducting career. You do have to think strategically. It is a bit like chess.

But wasn't he right in one way: you do have to think long-term about your conducting career. You do have to think strategically. It is a bit like chess.

Not completely and I'll tell you why. Because, in the end, it depends on what's important to you. Is the career important to you and the music the vehicle for the career or is it the other way round, where the career is the reflection of what your interests in music are? It is only a matter of priorities. It has to do with the person. No one else can tell you that. It is for you to do it one way or another. It's actually pretty simple. You think I would have wanted to impose an exile on myself going to Grand Rapids in order to be in Grand Rapids? No. It was simply an artistic opportunity that I felt that I had to have at that time of my life and Karajan confirmed this for me. When I went to Berlin in 1985, we talked for a long time. He asked me what I was doing. I said that I am still at Grand Rapids, Michigan. "It's my Ulm", I said. That's what Ulm was for you. [The Stadttheater in Ulm was where Karajan started out as Kapellmeister; Karajan is pictured above with his Ulm orchestral colleagues] And he laughed and said, "You're absolutely right. A few years of that and you're ready for anything." For artists of his generation there was no other way. This is how they did it, this is how they knew it. It built up a foundation for the rest of their life. That is what I believed then and it is what I still believe today.

Do you ever, however, get jealous with conductors like Dudamel, who seemed to have breezed into their big posts while you have slowly but surely worked your way up to the top over many years?

Everybody just has to be themselves. Gustavo is being himself. Is it his fault that he has so much talent? Is it his fault that he is so photogenic or charismatic? Is he the one who says that he is the next Karajan? No. So where is the problem? He has to be himself. I have to be myself. It is not in fact an interesting question. The only question that is interesting is what one does with this. That's the only interesting thing to observe and contemplate: to see whether it is convincing or not. How one gets there...? [Harrumphs] Look at sport. Runners. There are those who are amazing at 100 metres but couldn't survive three miles and there are marathon runners who wouldn't make 100 metres. Everyone has his destiny.

Add comment