Yevhen Stankovych is Ukraine’s most important living composer and – after decades of writing music that seems to grow from this country’s rich black earth, tribulations, literature and folklore – he now contributes, with his latest piece, the most cogent musical event of the current calamity. Psalms of War premiered last weekend at the Lviv National Opera, is not only the most powerful musical expression of Ukraine’s pain and just war, but probably the most impactful war music of our time.

It is one thing to write a staged piece about war, with a set of apartment blocks collapsing after a missile attack, and quite another to do so from deep within a war, when that same set is for real beyond the theatre exit, the scent of charred masonry still hanging in the air over the town of Hroza to the East, where the death toll from last week’s atrocity has reached 59 – mostly family and friends attending the funeral of a soldier. Both as a work of art, and occasion, Psalms of War is at once visceral, shattering and epic.

“I don’t know what this piece is”, Stankovych (pictured right) says over coffee in his favourite Italian bistro at a shopping centre on the outskirts of Kyiv, four days after the premiere. “It’s not an opera; it’s neither an oratorio nor a cantata. It’s a synthesis, I suppose, of what we are feeling in this moment. We can only write what we feel – the meanings will come later”. “For me, it’s more of a Requiem”, says the librettist Vasyl Vovkun, Director of the Lviv Opera, who staged the work. “A distillation of all our wars with Russia into this present one, and into this piece”.

“I don’t know what this piece is”, Stankovych (pictured right) says over coffee in his favourite Italian bistro at a shopping centre on the outskirts of Kyiv, four days after the premiere. “It’s not an opera; it’s neither an oratorio nor a cantata. It’s a synthesis, I suppose, of what we are feeling in this moment. We can only write what we feel – the meanings will come later”. “For me, it’s more of a Requiem”, says the librettist Vasyl Vovkun, Director of the Lviv Opera, who staged the work. “A distillation of all our wars with Russia into this present one, and into this piece”.

The soundscape is Stankovych’s own, cautiously explicable to those unacquainted with his music by reference to, perhaps, Janáček’s operas, John Adams’ Gospel According to the Other Mary and, ironically, the war symphonies of Shostakovich. “He is like a mid-20th century composer writing for our age”, says the premiere’s conductor, Ivan Cherednichenko.

Stankovych began work on this music after his grandchildren had fled their house in the Kyiv suburb of Bucha for the Western Carpathian region, before Bucha’s occupation early on during the full-scale invasion (and scene of some of the most heinous war crimes), during which their home was destroyed. He continued while undergoing surgery twice for his heart, and a further two operations on his back. These personal ordeals palpably permeate the sonority, aura and impact. Cherednichenko lost both his parents to Russian war crimes on the same outskirts of Kyiv early in the war, and this indescribable loss inevitably infuses the playing he demands from his musicians – he, as well as the composer, speaks with this remarkable music. “It’s very hard for Cherednichenko to conduct this”, says Stankovych, “but what is an artist to do with such a situation, if not this?”

Stankovych also has a wonderfully droll, diagonal sense of humour: I put to him a question asked by TV reporters to Cherednichenko and choirmaster Vadim Yachenko before the dress rehearsal, that it is too early to present such a piece to Ukrainians who may not want to experience their real-life trauma in a theatre – to inflict it upon them. “My piece, too early?” echoes Stankovych, and replies: “Is the war too early? It’s certainly here, it’s hanging on the air. And my music would be too late after the war is over. If I didn’t want to terrify people, I wouldn’t have written this. This is not art for art’s sake, this is art for when the windows are shaking and the bed is jumping from another air raid. When it’s all flying at you for real”. And on the awful sound of air-raid sirens played on trombone, which the audience hears almost every night in reality? “It’s not my fault there’s a siren there, it’s Vladimir Putin’s fault! He put it there!”.  In interview, Cherednichenko says: “there is an argument that this is not the right time for such a piece. But I think it is; a work like this can motivate and empower people, and ensure that we will never forget the feelings of this moment. There’s a catharsis in this”. He adds: “Stankovych is a composer of truth. All his major pieces have a huge dramatic narrative that stretch the soul, and this is one of them.”

In interview, Cherednichenko says: “there is an argument that this is not the right time for such a piece. But I think it is; a work like this can motivate and empower people, and ensure that we will never forget the feelings of this moment. There’s a catharsis in this”. He adds: “Stankovych is a composer of truth. All his major pieces have a huge dramatic narrative that stretch the soul, and this is one of them.”

Indeed, Stankovych writes this piece on the same vast scale that characterised his Holodomor Requiem, about the great Ukrainian famine engineered by Joseph Stalin between 1932-5, premiered in 1993. When the Fern Blooms, a work which evokes the pagan ritual of Ivana Kupala night in early July, blends midsummer in the Julian calendar with courting and nuptial rites and bonfires. It was banned by Soviet authorities in 1978, after KGB agents attended the dress rehearsal, and not premiered until 2011. Latterly there’s Stankovych’s mighty opera The Terrible Revenge, adapted from the story by Gogol, and didactically appropriated from the Russian prose into a Ukrainian libretto. Composed across three huge acts, it tells the story of the Antichrist being overthrown by a little boy, having violated and killed his own daughter. The opera was written before the full-scale invasion of 2022, but was eerily prescient of it, causing Cherednichenko to call Stankovych “a musical prophet”.  For Psalms of War, all this immensity is condensed into 50 terrifying minutes.

For Psalms of War, all this immensity is condensed into 50 terrifying minutes.

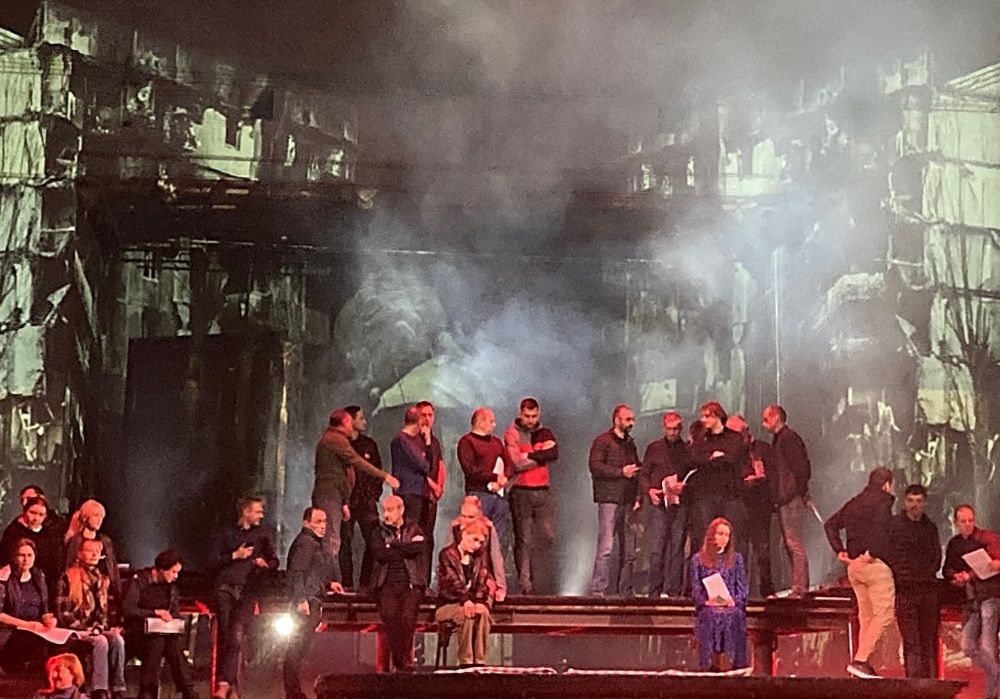

“When the full-scale invasion happened”, says Stankovych, “I imagined: what if my grandchildren were still in Bucha? - that is when and how I started this work. And I continued while two months in intensive care with a broken spine”. Stankovych had discussed ideas for a piece with Vovkun, a friend and collaborator over decades (pictured above courtesy of Lviv National Opera receiving applause at the end of the performance; behind him are Cherednichenko and Yatsenko), and Volodymyr Sirenko, conductor of most of Stankovych’s recent recorded music. “It just happened”, says Stankovych. “I haven’t come to myself yet – but it happened. It wasn’t instinctive, it was done very consciously. Instinctively, I wish I could have a drink; consciously, I composed this music”.

This Lviv premiere is the main version of a piece that may yet evolve, according to the composer. There had been a ‘pre-premiere’ in Kyiv five days beforehand, with the second and third movements inverted, and a traditional song, The Black Earth, sung a cappella. This Kyiv performance had been played by the National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine, currently touring the UK, under Sirenko’s baton, with artistic director and choirmaster Yevhen Savchuk. “There is no definitive version”, Stankovych admits, “I’ve done my work, now my good friends can do with it what they want. It can be for various places, with various orchestras”.

This most ambitious and dramatic vision in Lviv is realised – and the libretto written - by Vovkun. “We invited all our staff to the premiere”, he says, “so that we can all be part of this together, and with what is happening onstage. The children are not actors, they are the choir’s actual children”. For the first time in living memory the portrait of Ukrainian diva Solomiia Krushelnytska, which adorns the monumental staircase in the lobby of this glorious Hapsburg-era house, is covered, and in front of it a haunting statue placed, of a figure apparently seared by fire when illuminated red: 2022, by sculptor Igor Grechanyk (pictured above)

This most ambitious and dramatic vision in Lviv is realised – and the libretto written - by Vovkun. “We invited all our staff to the premiere”, he says, “so that we can all be part of this together, and with what is happening onstage. The children are not actors, they are the choir’s actual children”. For the first time in living memory the portrait of Ukrainian diva Solomiia Krushelnytska, which adorns the monumental staircase in the lobby of this glorious Hapsburg-era house, is covered, and in front of it a haunting statue placed, of a figure apparently seared by fire when illuminated red: 2022, by sculptor Igor Grechanyk (pictured above)

The mood, and its sonority, are established immediately. The first movement - entitled “Music for War” – is launched by martial timpani, rushing strings, a tolling bell, and that wail of a siren on trombone: Ukraine’s reality dramatised in sound. The brass leads an orchestral gallop pregnant with menace and the violence to come; searchlights scan the sky as the choir clambers to its positions on layered platforms made with what look like railway tracks, to give a sense of flight, and down into the lower level inevitably evocative of a bomb shelter. They carry wheelie bags, teddy bears, portable pet baskets and other quotidian items that have become icons of this war. Behind then, a flaming sun and cool moon converge, until the latter eclipses the former, bringing us into darkness of both night and noon.

The opening sung lines are defiant rather than fearful: “Fight, Fight / God help you!”, declamatory, from full choir. But once the first aural pounding is done, the choir proceeds with a wordless lament, echoed by flute and piccolo, like a reckoning after the attack. “Sometimes there are no words”, as Vovkun had reflected earlier, “that is why we have music”. Pictured below: :Lviv Opera House. During rehearsals, Cherednichenko had been estimably demanding, resolute almost to the point of exasperation – and to cogent effect: commanding a committed orchestra, and a score that is tense, dense and intense, with passionate articulacy. Stankovych composes with exceptional potency for woodwind, and a lachrymose motif on oboe now cues the Lord’s Prayer, spoken sotto voce by some in the choir, while others, unbelievers perhaps, stare skyward, or cross their arms and reflect. The incantation builds into a fortissimo chorus accompanied by kettledrum - a wall of sound, during which the set changes from the eclipse to the ruined buildings after a missile attack. An orchestral passage describes its aftermath, with five tolls of a bell, shrill piccolo, and a dissonant cadence of sorts.

During rehearsals, Cherednichenko had been estimably demanding, resolute almost to the point of exasperation – and to cogent effect: commanding a committed orchestra, and a score that is tense, dense and intense, with passionate articulacy. Stankovych composes with exceptional potency for woodwind, and a lachrymose motif on oboe now cues the Lord’s Prayer, spoken sotto voce by some in the choir, while others, unbelievers perhaps, stare skyward, or cross their arms and reflect. The incantation builds into a fortissimo chorus accompanied by kettledrum - a wall of sound, during which the set changes from the eclipse to the ruined buildings after a missile attack. An orchestral passage describes its aftermath, with five tolls of a bell, shrill piccolo, and a dissonant cadence of sorts.

The second movement was added at Vovkun’s urging, and its inclusion only finalised during a phone call with the composer during a rehearsal 48 hours before the premiere (Stankovych was unable to attend in Lviv, for health reasons). It sets a folk song of yore, “The Black Earth”, about the burial of a Cossack warrior, for deep baritone, who begins his solo within the shelter’s darkness before taking the stage, conjoined by the choir, building to a further onslaught of sound, both vocal and orchestral.

Once it passes, like another air raid, the third movement – an adagio of sorts - is cued by a ringing triangle and haunting four-note motif on flute, picked up as a five-note phrase by solo soprano from within the choir, again wordless, then conjoined pianissimo by the rest of the chorus. “It is a lullaby for children killed during the war”, says Stankovych. “What words do you use when a child is killed? There are none”. Children on stage huddle around their (real life) mothers, for comfort and protection – for this passage is about those who looked and played like them, until their lives were ended by shards of burning shrapnel, and falling masonry. A bell tolls, the xylophone shimmers. But then even this pensive, reflective passage wherein turmoil abates into sorrow, is brutally shattered by yet another assault of sound: a fortissimo barrage of swaying strings, furious kettledrum, hammer on anvil, and dissonant woodwind. It finally calms; a woodblock beats what could be time, God’s metronome, or a heartbeat accelerated by the fearful strain and stress of it all. Pictured below: a scene from Psalms of War. courtesy of Lviv National Opera The piece, like the war, is relentless, and denies repose. Each time the music tries to catch breath, reaches an orchestral plateau or settles into a cadence of cathartic respite – even when it is anxiously dissonant - that moment of reflection, is assailed by another brutal charge on kettledrum, hammer and anvil. Lyrical passages of yearning on strings are whipped out their attempt at reprieve by crashing timpani. So there is this sense, as in life outside, that the attack – the missile, the drone – can arrive to kill at any moment. Such is the lottery of life and death in Ukraine, conveyed even in the production’s minutest details: while the music surges, children play scissors-paper-stone… luck of the draw whether you live or die.

The piece, like the war, is relentless, and denies repose. Each time the music tries to catch breath, reaches an orchestral plateau or settles into a cadence of cathartic respite – even when it is anxiously dissonant - that moment of reflection, is assailed by another brutal charge on kettledrum, hammer and anvil. Lyrical passages of yearning on strings are whipped out their attempt at reprieve by crashing timpani. So there is this sense, as in life outside, that the attack – the missile, the drone – can arrive to kill at any moment. Such is the lottery of life and death in Ukraine, conveyed even in the production’s minutest details: while the music surges, children play scissors-paper-stone… luck of the draw whether you live or die.

The fourth and final movement is a setting of lines Stankovych selected from the Book of Psalms, and mainly from Psalm 59, defiant both in its Biblical promise of deliverance, and last, vast attestation in the music. But the beginning of the end, a heave in orchestra and choir like a rip-tide of sound, is not the usual ‘triumphal’ ending promised by most war music: here, even the swell towards affirmation that hallmarks many a great finale is interrupted more than once by fusillades and aggressions. “In the middle of a war, there can only be a half-way towards the final chord”, remarks Stankovych. “You’ll notice that the four-note lullaby is there, but there can be no real ‘ending’ while the war still rages” Pictured below: Stankovych reading from a book of poetry by dissident Vasyl Stus, who "died" in the Perm 36 camp during supposed Perestroika. Behind him is his daughter Rada, opposite her Roman Veretelnyk, who teaches journalism and literature at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla and who presented Stankovych with the volume, and on the right Ed Vulliamy).  Cherednichenko says that “each piece by Stankovych affirms our nation within the world of music”. With this music, Stankovych stakes a claim from within the war, but also beyond it and beyond Ukraine, into the canon of great contemporary music – this Lviv production must come to Western Europe and the USA. A group of soldiers was invited to the Lviv dress rehearsal last Friday, sitting along rows 14 and 15 of the stalls. As one of them put it afterwards: “We have come to the theatre to see reality”.

Cherednichenko says that “each piece by Stankovych affirms our nation within the world of music”. With this music, Stankovych stakes a claim from within the war, but also beyond it and beyond Ukraine, into the canon of great contemporary music – this Lviv production must come to Western Europe and the USA. A group of soldiers was invited to the Lviv dress rehearsal last Friday, sitting along rows 14 and 15 of the stalls. As one of them put it afterwards: “We have come to the theatre to see reality”.

- Ed Vulliamy is a writer and librettist of “Who’d Ever Think It Would Come To This?”- A Cantata for the Irish Civil War

- More opera reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment