Patrick Barlow’s last play was parked in the West End for nine years. The 39 Steps finally closed this autumn, but not before travelling all over the world, most prestigiously to Broadway but also, among other destinations, to Russia, Japan, Australia, Korea, Hong Kong and France. There have been no fewer than eight different productions in Germany, including one with an all-female cast. So the question naturally pinging around Barlow’s cranium was: how exactly do you follow that?

In 2012 he came up with the answer in the form of a redux version of Ben Hur. It was produced at the Watermill Theatre in Newbury with – cue alarums, trumpets and fanfares – a mighty cast of four, tasked with somehow encompassing the epic dimensions of the story of a wealthy Judaean captured and sold into Roman slavery only to become an all-conquering charioteer while, in the background, a young prophet preaches sermons from mounts and ends up crucified for his pains. It’s taken a while, but it is now resurfacing at the Tricycle Theatre where The 39 Steps also had its first London run. Barlow tells theartsdesk about its genesis, and its roots in his pioneering work as Desmond Olivier Dingle, the artistic director of the almighty National Theatre of Brent.

JASPER REES: Is The 39 Steps a template for Ben Hur?

PATRICK BARLOW: I’ve always wanted to do a theatrical version of Ben Hur, all my life since I was 12. Then after The 39 Steps I thought, you can do epics with four people. I don’t know whether you can do it with every inappropriately large play.

What was your first encounter with Ben Hur?

I didn't know there was an old one. It’s in black and white and the shots and compositions and the crowd scenes – a scene in the market with chickens running around and cattle and slightly overacting slaves and Romans is quite extraordinary (pictured: Roman Navarro in the 1925 version). But no one knows that. The one I fell in love with is the 1959 Charlton Heston version. Aged 12 I was getting very into religion. It had everything: Romans, Jesus, chariots, blood, slavery. Everything you could possibly want. So I fell for it in a big way. I was C of E but I found the whole Christian story, as I still do, rather overwhelming and very meaningful. It rang lots of bells and chords. It’s very dramatic. Marvellous nativity, marvellous crucifixion. It’s quite important to say that the film was what got me into it but actually my version is based on the book. A lot of the story of the film is from the book but this is very much not a play of the film. It’s a play of the book by "Lew" Wallace who was a Civil War general who wrote lots of books about Peru and stuff and suddenly out of the blue wrote this extraordinary book which has never been out of print. You get them in American bookshops. There is a brilliant woman character in it called Iris that isn’t in the film. And the ending is quite different. They’re still cured of leprosy but there is much more of a Jesus character in it. In the film he’s just a mystic figure. You never see his face. In mine he does appear quite seriously and he talks quite a lot.

I didn't know there was an old one. It’s in black and white and the shots and compositions and the crowd scenes – a scene in the market with chickens running around and cattle and slightly overacting slaves and Romans is quite extraordinary (pictured: Roman Navarro in the 1925 version). But no one knows that. The one I fell in love with is the 1959 Charlton Heston version. Aged 12 I was getting very into religion. It had everything: Romans, Jesus, chariots, blood, slavery. Everything you could possibly want. So I fell for it in a big way. I was C of E but I found the whole Christian story, as I still do, rather overwhelming and very meaningful. It rang lots of bells and chords. It’s very dramatic. Marvellous nativity, marvellous crucifixion. It’s quite important to say that the film was what got me into it but actually my version is based on the book. A lot of the story of the film is from the book but this is very much not a play of the film. It’s a play of the book by "Lew" Wallace who was a Civil War general who wrote lots of books about Peru and stuff and suddenly out of the blue wrote this extraordinary book which has never been out of print. You get them in American bookshops. There is a brilliant woman character in it called Iris that isn’t in the film. And the ending is quite different. They’re still cured of leprosy but there is much more of a Jesus character in it. In the film he’s just a mystic figure. You never see his face. In mine he does appear quite seriously and he talks quite a lot.

Can Anglicans see this without going away apoplectic?

Oh, they can. It’s very respectful, because I’m very respectful. I was brought up with the Christian religion. The religion I think has gone horribly astray but the message of the man is very very amazing and one we should listen to and adhere to on a daily basis.

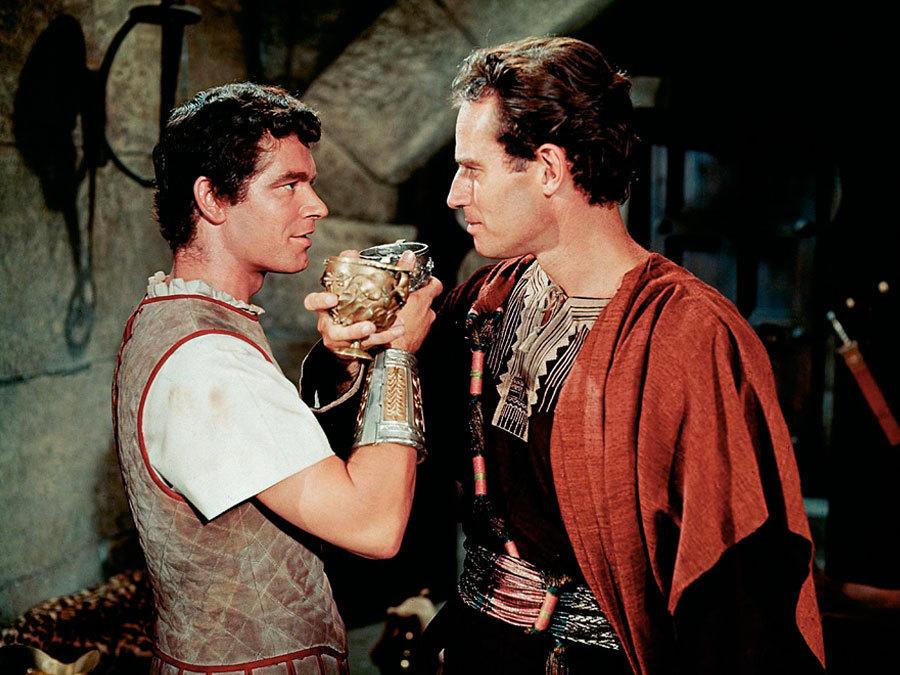

How much homoeroticism will be in the play? I’m thinking of the undercurrents between Charlton Heston and Stephen Boyd (pictured) as Ben Hur’s nemesis Messala in the William Wyler film.

How much homoeroticism will be in the play? I’m thinking of the undercurrents between Charlton Heston and Stephen Boyd (pictured) as Ben Hur’s nemesis Messala in the William Wyler film.

There’s a couple of homoerotic moments. There’s also a full-scale Roman orgy, beginning of Act Two.

All your work that I know has been very specifically about trying to get people to laugh. Is that your primary aim with this? Or have I misread the entire career?

You’ve misread the entire thing. The whole canon has been rather simplified! There should be pathos there but I only choose in my work – or in the National Theatre of Brent – stories that are meaningful to us and have something to say to us. We did the story of the Dalai Lama. He’s a bit like a naughty teenager because he doesn’t want to learn about Buddhism but has to, and that’s the joke. But I also am very interested in Buddhism and the way of dealing with the world from a Buddhist perspective, peace and a bit of understanding.

We did the Charles and Diana story, Love Upon the Throne, in the West End, and although I wasn’t madly interested in doing a big royal thing I was very interested in a love story and how a marriage can break up. My own marriage had just broken up. So it’s a way of exploring stuff which I take very seriously in a ludicrous way, but I want the seriousness to be there as well. What I find most engaging is making the odds as impossible as possible. So it’s almost impossible for four people to play 60,000 people, a galley battle, a chariot race. So in a way it should be even more ludicrous and funny because it’s even more impossible. Ben Hur has one actor who plays Ben Hur, a woman who plays all the women parts, and then two guys who play all the other male parts.

Could you have guessed that The 39 Steps (pictured) would have quite such longevity?

Could you have guessed that The 39 Steps (pictured) would have quite such longevity?

I had no idea. I thought the idea was great. Edward Snape came up with the original idea of adapting The 39 Steps as a four-man show and came to me with minimalist experience. He said, “I can barely pay you up front.” I was so attracted to it and when I saw the movie I just fell in love with the idea of putting a movie onstage. I thought, if there’s any fairness in the world it should really, really work, this. But often these things don’t. So I was blown away by how successful it’s been and how it appeals to people. It has afforded me the fortune of being able to pick and choose much more what I do. I don’t suddenly find myself having to do grim telly jobs to pay the rent.

What did Maria Aitken bring as director?

We put it on in Leeds, then it went on tour, then the director Fiona Buffini left and then we got interest from the Tricycle and Nick Kent knew Maria very well and we had a very nice conversation and she said, “I’d love to take this up a step.” Fiona wasn’t available. Maria took it on, and she added all sorts of clever witty things. The actors loved her and she brought it into an even clearer focus. The show in Leeds that Fiona did – we got mixed reviews for that. We got a fantastic cast. We got a great theatre at the Criterion and it just started going round the world. People love watching the ingenuity. There’s a good story as well, thanks to Mr Hitchcock. The original is very, very slow. It’s four people attempting the impossible and taking it very seriously and battling with quite a difficult set that doesn’t always behave, quite difficult props that aren’t always there on time, struggles between the actors. Ben Hur has very much the same feel but this is even more so.

Does all of this grow out of National Theatre of Brent? Could you have done it without it? (Pictured: Patrick Barlow as Desmond Olivier Dingle with John Ramm as Raymond Box)

Does all of this grow out of National Theatre of Brent? Could you have done it without it? (Pictured: Patrick Barlow as Desmond Olivier Dingle with John Ramm as Raymond Box)

No, I don’t think so. The work we did over the years with different companies and actors – I’ve learnt so much about minimalising stuff and using the audience, and being able to switch from ridiculous to sad – and very quickly. All those Brent things I bring to these slightly larger epics. We mainly do radio because we can write it, rehearse it and put it on in a couple of days. If it’s theatre, it’s a much longer process.

Is Desmond Dingle, the vainglorious amateur theatre-maker you created for National Theatre of Brent, based on anyone?

The funny thing about Desmond is he doesn’t know what he’s talking about. Raymond is much cleverer, but doesn’t know he is. I like that idea. There’s bits of my really annoying pompous side in there, and rather ratty. But there are a couple of directors I’ve worked with in my early career who were very pretentious. Desmond’s original story is he was entertainments officer on some cross-channel ferry. The pretentiousness of an entertainments officer who thinks he can do great Shakespeare came out of the ether. I’ve known a lot of bullies in my time, and I think they are fair game. They are very around in the theatre. Desmond is like that.

Could Desmond play Ben Hur?

Desmond would adore to play Ben Hur. He’s fantastically wrong for it. He’d be horribly pompous and he would get very embarrassed in the orgy scene. He finds it a bit hard doing sex scenes. He did play Lady Chatterley once. That was the most dangerous he ever got. Raymond got a bit carried away. Never again.

Add comment