The monster has come alive and there’s nothing I can do to stop it. Thirteen actors playing three generations of a very explosive family arrive in full period costume. Towering Dexion shelving units, heaving with foam and cushions and fabrics and off-cuts, reach to the rafters and snake around the entirety of the stage. They form the looming, metallic skeleton of a hugely intricate replica of a three-storey rubber emporium in 1968. The lights, the music, the mingling polyphony of street life, traffic and heavy machinery, flood the theatre. The Kraken has awoken and there’s no way back.

It’s always an odd experience for a playwright to hang about at a dress rehearsal. This thing you’ve conjured in your little room has now violently unshackled itself from your imagination and taken on a life of its own. And there you lurk at the back of the auditorium, surplus to requirements, this spectral figure only capable of getting under the everyone’s feet. As I watch I quickly realise I’ve had this sensation before. My mind hurtles back to the school holidays I spent working for my Dad. Not only did I feel equally useless then, but it was the inspiration for this play, now about to open at Hampstead Theatre. (Pictured below: Ryan Craig)

My father ran a foam rubber shop on the Holloway Road. The shop employed my grandfather, great uncle, and a mixture of staff from the local area and skilled émigrés from Iraq and Nigeria. It was a very specialised business dealing with items as varied as sofa-beds, bean-bags, crumb-stuffed cushions, latex tubing, sheeting, matting and mattresses, rubber flooring and underlay, vinyl, PVC and polypropylene for packaging and coverings. These materials were heavier than they looked, perilously difficult to cut and shape, and intricately priced so I was deeply ill-equipped to contribute.

My father ran a foam rubber shop on the Holloway Road. The shop employed my grandfather, great uncle, and a mixture of staff from the local area and skilled émigrés from Iraq and Nigeria. It was a very specialised business dealing with items as varied as sofa-beds, bean-bags, crumb-stuffed cushions, latex tubing, sheeting, matting and mattresses, rubber flooring and underlay, vinyl, PVC and polypropylene for packaging and coverings. These materials were heavier than they looked, perilously difficult to cut and shape, and intricately priced so I was deeply ill-equipped to contribute.

Still, I had to serve, wrap, cut, go on deliveries, make the tea, answer the phones, and I was hopeless at all of it. The staff tolerated me because I was the boss’s son and this was a family business, but I was a gawky, clumsy, bookish boy, hot with embarrassment, and helplessly awkward, so I felt acutely out of place in this tough, earthy environment. My anxiety was sharpened by the knowledge that the business was increasingly at the mercy of a rapidly modernising world, and the future was always hanging in the balance. The destiny of the family and the business were tightly bound together, so there was an enormous pressure on my father’s shoulders.

After my play The Holy Rosenbergs at National Theatre, which touched on a family of caterers, I started to think there might be a rich seam to mine here in how a family business impacts on every member, whether they work in it or not. I was also interested in how the conflicting desires of an immigrant community to both integrate into the host society, and yet hold on to their ethnic roots in the face of hostility or ignorance, can sometimes create in its members a driving, innovative entrepreneurial spirit.

My father had begun his working life in on the East End markets alongside his cousins, father, uncles, and grandfather, a Jewish refugee from Eastern Europe who, like his wife, had fled the pogroms at the beginning of the 20th century. Arriving here penniless and alone, but hungry and strong, he found work in a factory fitting massive rubber tyres to trams. Family lore has it that one night he came home with a bag of rubber off-cuts and he and his young wife cut the scraps into items for sale on the markets. From this they invented and grew a profitable business, effectively monopolising the “rubber game” in the following decades.

But it’s what happened next that captivated my youthful imagination. Growing up, I would hear stories of the power struggles between the generations, the four sons and their sons, of their competing agendas and baroque bust-ups that became the stuff of legend, and these stories nagged away at me for years.

But it’s what happened next that captivated my youthful imagination. Growing up, I would hear stories of the power struggles between the generations, the four sons and their sons, of their competing agendas and baroque bust-ups that became the stuff of legend, and these stories nagged away at me for years.

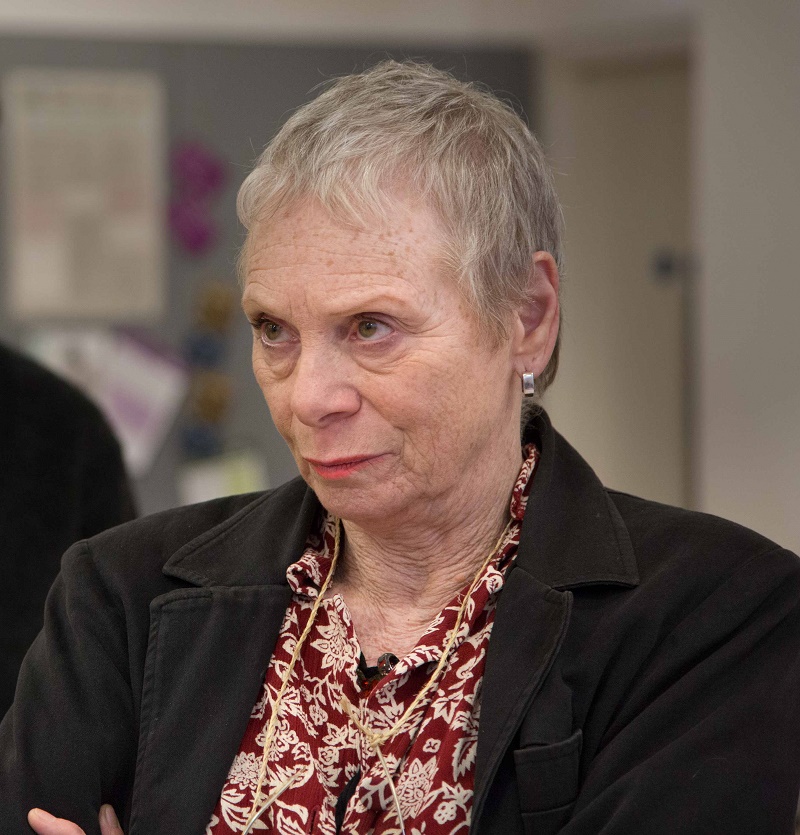

Finally, attempting some innovation of my own, I created the Solomons and their formidable matriarch Yetta (played by Sara Kestelman, pictured above), and set this fictional family in the rubber shop of my youth. The play, which follows their progress over two decades of tempestuous political and economic change, is full of punch-ups and escapades and parties, backstabbing and betrayal and, underneath, a lot of love and affection.

Working with Edward Hall at Hampstead, I honed the text, and then with the designer Ashley Martin-Davis, the crew and the cast began to realise it physically. Now, as I watch this skilled and dedicated group of people swarming over this monumental set, I wonder what the hell I started. What began as a hypothetical concept in my little room has become a living breathing creature of its own.

- Filthy Business is at Hampstead Theatre from 10 March to 22 April

- Read more First Person articles on theartsdesk

Add comment