As I write this, we've just had our final day in the rehearsal room and are going into tech onstage next week with my new play, which is also reopening the Donmar not only to live performance but follows major renovations at their home address.

It’s a funny thing, but I can find it hard to describe what the play is "about" at this time. It has been unmade and remade, become something vividly new outside my own head, which is the process of making a play. If I go back to the initial impulse, it is about a young couple, roughly here, roughly now, and their relationship across roughly 10 years. They have inherited a trauma from the distant past which endlessly binds them to each other in love, and forces them apart in violence.

The inspiration came out of a surprising revelation between me and a man. We discovered our families were from the same town in what is now Poland, but would have been the Pale of Settlement when my Jewish ancestors lived there. It struck me that you could write a play about a relationship made both inevitable and impossible by violence perpetrated in the past, and that got me thinking about inherited trauma, and trans-generational trauma, and the experience of the descendants of both victims and perpetrators. How do shame and guilt play out now, and what of rage and revenge? Can we survive the crimes of the past that continue to be felt in the present?

The inspiration came out of a surprising revelation between me and a man. We discovered our families were from the same town in what is now Poland, but would have been the Pale of Settlement when my Jewish ancestors lived there. It struck me that you could write a play about a relationship made both inevitable and impossible by violence perpetrated in the past, and that got me thinking about inherited trauma, and trans-generational trauma, and the experience of the descendants of both victims and perpetrators. How do shame and guilt play out now, and what of rage and revenge? Can we survive the crimes of the past that continue to be felt in the present?

This was a while ago: 2015, perhaps 2014. I immediately knew the play's form and structure. and based it, loosely, on the musical idea of theme and variation, where a theme is repeated and developed along the way. I felt that you could explore an inherited trauma that way, by showing this relationship through a series of "variations" of scenes, and then showing the "theme" from where all this love and violence comes. In that sense this is two plays, bound thematically and by cast-doubling and by many textual and visual echoes.

The contemporary politics came later. I didn’t know how to write that part of it until, only last February, I read a review by Joseph Roth of a book about an illicit affair. He describes the “burning idyll” of the lovers and then writes, “All around is the world war. Its murderous sound even penetrates behind the lovers' locked door and fills the hour in which the blood speaks. In this way it is a war novel too, though set in the hinterland. Because a true writer, even if his story is somewhere far away, will not escape the din of his time. It determines the tempo of his stride, slows it down or gives it wings.” I immediately understood that what I was lacking was “the din of my time” – that I had written not just a play about inheritance and the past but also a play about the present and perhaps where we might be going.

I needed a historical moment that could speak to our moment now, that's to say of the old ways crumbling and what comes rushing to fill the void of vanishing socio-political hegemonies. I chose the fall of the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1918 and the bloom of violent nationalism in its wake to reflect what could be described as the fall of Western late neoliberal capitalism, which has received multiple shocks these past decades and is leaving space for even uglier nationalist and populist politics. I think many people would agree that the din is loud these days, and it doesn’t sound good.

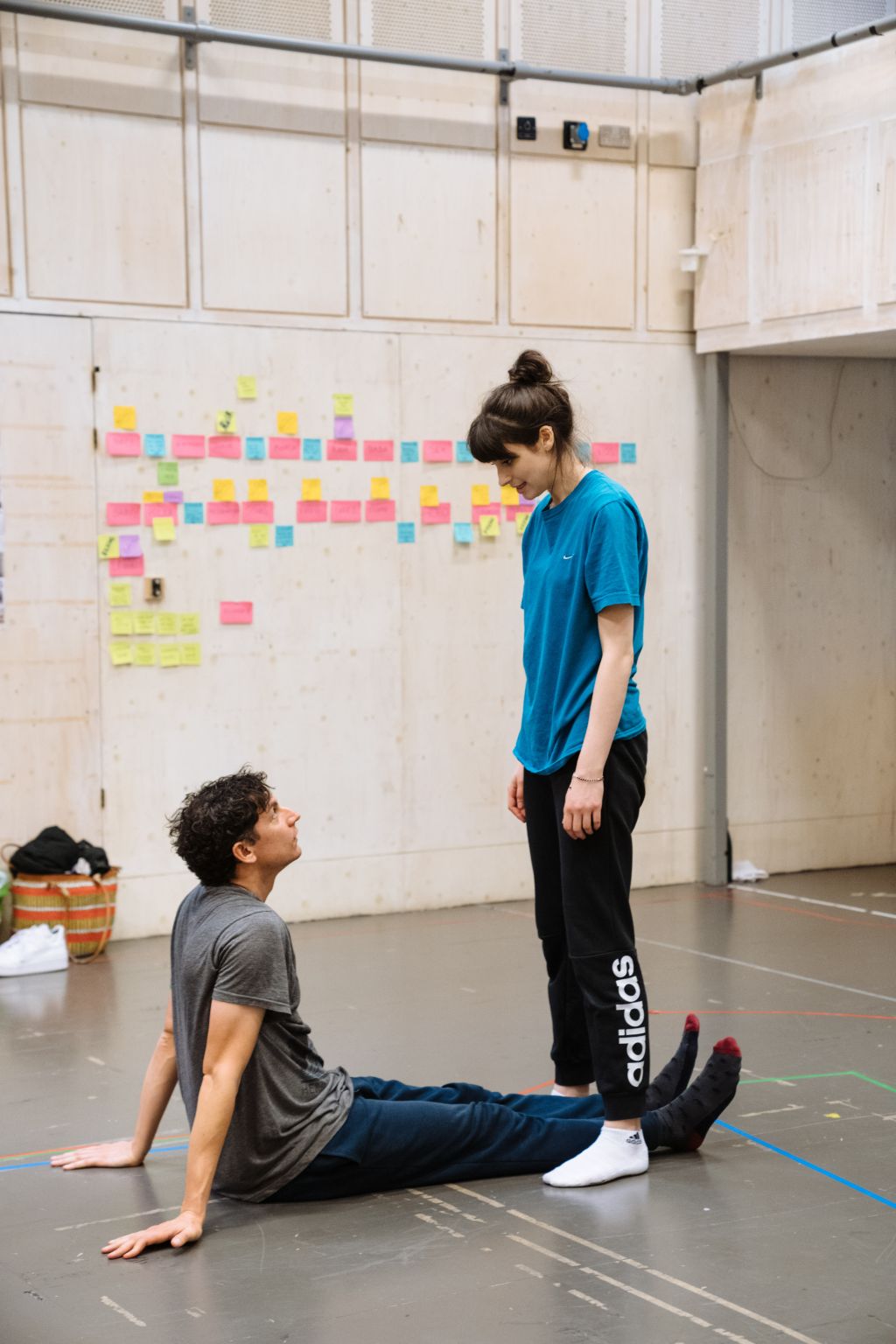

I’ve particularly enjoyed working with a movement director, Yarit Dor: a new experience for me. In our first weeks we did a lot of script and table work, uncovering the characters and the themes and all the little echoes in the play and then did movement in the afternoons. The physical games played with between Yarit and our three actors, Tom, Abbie and Richard, showed me the impulses that lie beneath text in a new and profound way. (Tom Mothersdale and Abigail Weinstock, pictured above)

People may wonder how Love and Other Acts of Violence may fit into other work of mine, a question that always unnerves me because I worry I’m supposed to have a style or, worse, some grand theory of art. Perhaps other people would be better at describing my work, how it fits, how it differs… For me, the play tells me how it wants to be written, and until it does I don’t start writing. You could call this the voice of the play, if you wanted. And each play has a different voice, again for me.

People may wonder how Love and Other Acts of Violence may fit into other work of mine, a question that always unnerves me because I worry I’m supposed to have a style or, worse, some grand theory of art. Perhaps other people would be better at describing my work, how it fits, how it differs… For me, the play tells me how it wants to be written, and until it does I don’t start writing. You could call this the voice of the play, if you wanted. And each play has a different voice, again for me.

One pattern I have started noticing is that roughly two-thirds of the way through rehearsals everyone collapses because the play feels so dark. And then I spend the rest of rehearsals running around trying to convince everyone that what I have written is actually a comedy. Love and Other Acts of Violence is bleak, it’s true, but our director, Elayce Ismail (pictured above), has created a beautiful, caring and playful room for us to make it in. There has been a lot of laughter and a lot of silliness, which I think there has to be when you’re making the hard stuff: It’s how we get through doing it every day.

But I promise there is funny stuff too, even if I have to admit that this isn’t entirely a comedy.

Add comment