You don’t know Homer’s Iliad until you’ve heard it read aloud, all 24 books – not quite every line, but almost – and 16 hours of it. Yesterday's marathon was surely something like the events in which the Athenians kept the oral tradition going during their great Dionysiac festivals - in most things, at least, except the original feats of memory.

For “you don’t” above, read “I didn’t”, since despite having studied several of the later books for ancient Greek A-level, then the first 12 over one university year, it wasn’t until Simon Russell Beale started invoking the muse in the British Museum’s Great Court at 9am yesterday that the lights started going on. Illuminations kept flashing until Tim Pigott-Smith brought everything to a quietly moving close in the more intimate surroundings of the Almeida Theatre just before 1am this morning. Did Homer’s “sweet relief of sleep” come to me as it did to an exhausted Achilles? No chance; the mind was still racing.

Which is to say that Rupert Goold, as a little-advertised part of his already impressive Almeida Greek season, has pulled off one of the glories of the theatrical year, or let’s go further and add of London theatre history. How much was it actually directed? I'm not sure, since the only unity was in diversity. Still, the plan went flawlessly for the Almeida’s scheme – its 60-plus actors taking up the baton of Robert Fagles' excellent translation from one another without a hitch and giving us, into the bargain, an encyclopedia of different dramatic styles – but presumably not for many completists.

What made it all possible was a splendid livestream. Having switched on at the start, I blithely thought I could make my way to the British Museum at lunchtime and then proceed to the final Almeida stretch. I found myself transfixed, though, by the different performing styles, the revelations in unexpected portions of Homer’s text. To hop on the bike would have been to miss something crucial. So you must believe me when I say that I caught every reading, and think what you will of the pleasure I got from sitting there with my old volumes of Greek text to refer to (it all came flooding back).

It would, as it turned out, not have been too much of a loss to skip the dubious interpolation of Book 10, with its detachable tale of a night raid, and the endless battle sequences unenlightened by the usual great speeches or divine interventions of the next two “chapters”; the acting mostly took a temporary nosedive here, excruciatingly so from one actress (no point in naming and shaming except to say that she wasn't the admirable Sharon Small). But still one wouldn’t have missed the exceptions, the hypnotic delivery of Deborah Findlay and the sudden wake-up call of Simon Coates.

It would, as it turned out, not have been too much of a loss to skip the dubious interpolation of Book 10, with its detachable tale of a night raid, and the endless battle sequences unenlightened by the usual great speeches or divine interventions of the next two “chapters”; the acting mostly took a temporary nosedive here, excruciatingly so from one actress (no point in naming and shaming except to say that she wasn't the admirable Sharon Small). But still one wouldn’t have missed the exceptions, the hypnotic delivery of Deborah Findlay and the sudden wake-up call of Simon Coates.

Besides, to watch the levels of actors’ delivery was always instructive. Some of the younger, less experienced torch bearers waved their arms around too much, stumbled as if they hadn’t done much work on the text or gabbled. Some were scriptbound and never made eye contact; others, in their admirable attempt to be liberated and act out their narrative, lost contact with the pages before them – the only flaw in Kate Fleetwood’s highly-strung sequence (she should make a magnificent Medea in husband Goold’s forthcoming production all the same).

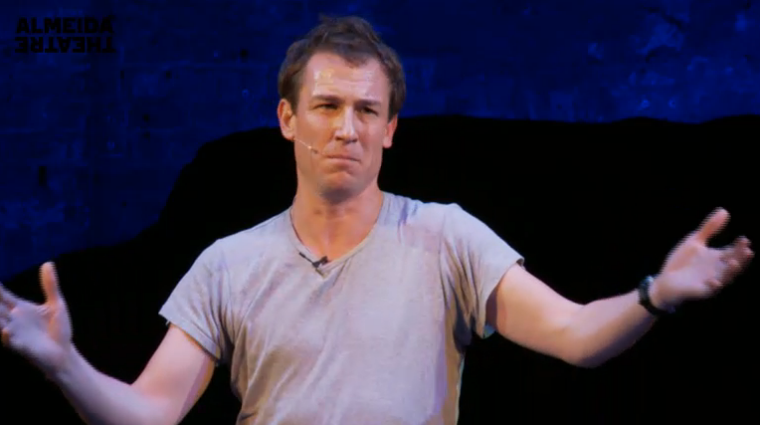

A spaced-out roll-call of confident Hamlets compelled. Russell Beale’s superbly gestural rhetoric at the start of Book 1 was matched by William (now Will) Houston’s relaxed and vocally well-modulated stint, as well as the total confidence of Sam West’s unerring delivery in the museum as many in the audience left to head to the Almeida. Best of all were the two who conjured the Trojan scenes before your very eyes, Rory Kinnear and the astonishing Tobias Menzies (pictured above) seeming to improvise as we had to bear the indignities of the dead Hector’s treatment by Achilles. Sometimes the merely good, like John Simm and Mark Gatiss, happened to be overshadowed by the great. Ben Whishaw may have been more magical in the Almeida – as his Dionysos absolutely was and is – but his eyes rarely left the page; and why the pencil in his right hand (work in progress?) and the embarrassing step out of character with a “sorry” for mispronouncing a name?

He shared Book 18 with a committed though externalized delivery from Bertie Carvel, Pentheus to his Dionysos; it took two great women, Hattie Morahan and Lia Williams, to take over and create the real word magic that had been missing from Carvel’s evocation of Thetis’s underwater kingdom. Most spellbinding of all was an earlier sequence enveloping the best speech in the entire Iliad, Achilles’ rejection of the embassy from the other Greeks desperate for him to rejoin the fighting from which he has retreated in the crucial quarrel with Agamemnon over a girl. The complexities of honour were beautifully nuanced by the ever-persuasive John Heffernan (pictured above), and Adjoa Andoh’s clarion characterisation of the ambassadors’ preceding council drew us into the heart of the story.

He shared Book 18 with a committed though externalized delivery from Bertie Carvel, Pentheus to his Dionysos; it took two great women, Hattie Morahan and Lia Williams, to take over and create the real word magic that had been missing from Carvel’s evocation of Thetis’s underwater kingdom. Most spellbinding of all was an earlier sequence enveloping the best speech in the entire Iliad, Achilles’ rejection of the embassy from the other Greeks desperate for him to rejoin the fighting from which he has retreated in the crucial quarrel with Agamemnon over a girl. The complexities of honour were beautifully nuanced by the ever-persuasive John Heffernan (pictured above), and Adjoa Andoh’s clarion characterisation of the ambassadors’ preceding council drew us into the heart of the story.

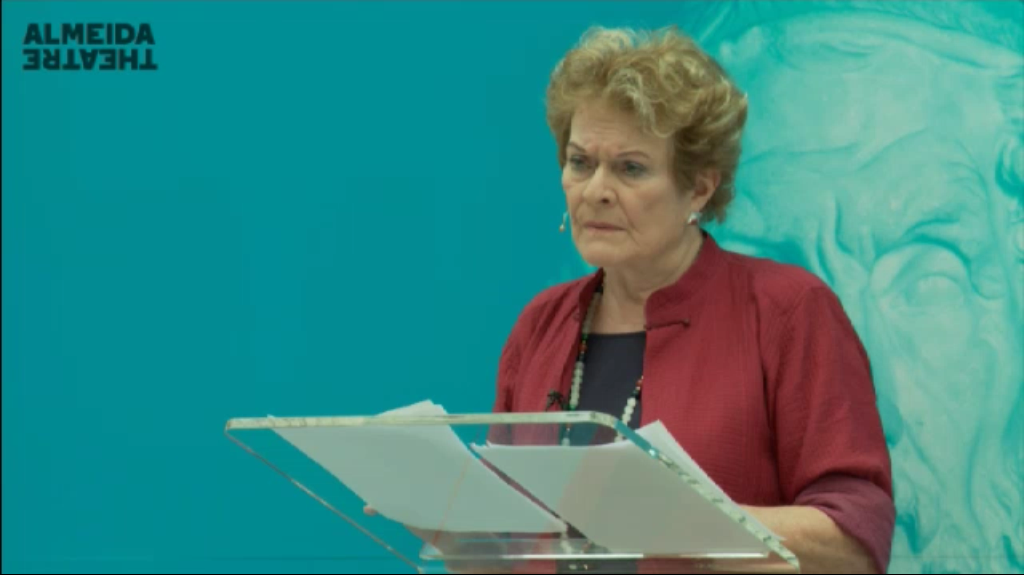

Other highlights are just too numerous to mention, though special accolades have to go to Janet Suzman, the first peak after Beale reminding some of us of her Helen in John Barton’s The Greeks, my first experience of classical epic on the stage decades ago; the adorable Jenna Russell for making the most of the fabulous comedy in which the gods bicker; Caroline Faber for projecting their climactic intervention in the fighting – she would have made a better Electra than Kristin Scott Thomas on this evidence; and Lisa Dwan, bringing a rare otherworldly quality.

The calm after all the cruelty and torment seeped into our bones through the beautiful modulations of Lesley Manville, before Pigott-Smith wrought his final spellDwan would keep saying “Zay-us”, for which there's some precedent, and “Patroculus”, for which there's none, but you quickly learnt to accept wrong or idiosyncratic pronunciations (starting with SRB’s “Archaeans” for “Achaians”, who also became “Ikeans” at one point) – superficial matters when the feeling was right. Wisely, the catalogue of the armies and their men was left to classicist Professor Simon Goldhill, who of course got all the names right and made it rather exciting, even if he could be breathless and – by the end of his stint – almost voiceless.

The grand manner some like myself find overblown, falsely thespy, surfaced only in Ian McDiarmid’s nevertheless charismatic conjuring of Achilles’ fight with the river and Simon Callow doing different voices for the funeral games in honour of Patroclus. But then this is a perilously long-winded digression when all should be winding up. I hope everyone hung around for the final book, the heartbreaking point at which Homer chooses to stop in the ninth year of the Trojan War as old Priam goes to Achilles’ tent to plead for the body of the cruelly mistreated, but miraculously unharmed, body of Hector. The calm after all the cruelty and torment seeped into our bones through the beautiful modulations of Lesley Manville, before Pigott-Smith wrought his final spell.

An epic with varying levels of intensity, then – how could it not be? – but still something I never thought I’d see as the media witter on about how a six-hour television War and Peace is essential “for the 21st century”. There are more people out there willing to concentrate over vast spans than the papers seem to realize. We found that out with the magnificent radio Tolstoy on New Year’s Day, and now this totally uncompromised venture proves it further. Odyssey next year, please.

Add comment