There are two fundamental ways to fillet the untranslatable poetry and ritual of Aeschylus, most remote of the three ancient Greek tragedians, for a contemporary audience. One is to find a poet of comparable word-magic and a composer to reflect the crucial role of music at the Athenian festivals, serving the drama with masks and compelling strangeness, as Peter Hall did in his seminal 1980s Oresteia at the National Theatre (poet: Tony Harrison, composer: Harrison Birtwistle, peerless both). The other is to cram it into modern dress and language, hoping that the eternal verities stick, which was the ultimately unsurmountable challenge faced by director/adaptor Robert Icke at the Almeida.

Icke makes it especially hard on himself, and on us, by writing a preliminary act dealing with the impossible sacrifice so often poeticized, discussed and revisited in Aeschylus’s trilogy. Political jargon and family endearments all of us recognise don’t make it easy to accept that any ruler would murder the young daughter he loves for strategic expediency, let alone for the god-decreed encouragement of some reluctant wind to back a crucial war campaign. How can we buy into any of the arguments in favour, and how can we not side unreservedly with the “This isn’t right” of Agamemnon’s aghast wife Clytemnestra? The Greeks loved a good debating contest, but this is too one-sided to make for plausible theatre. And normally any old murderous action reinterpreted through the medium of modern science makes me very queasy, but the clinical poisoning of little Iphigenia left me cold: too preposterous to strike home. It doesn’t help that the only successful politician to whom Angus Wright’s under-authoritative Agamemnon comes close to resembling is John Major, in the voice, at least. He’s no less stilted in the “I’m home”s and “how has our day been”s which are supposed to set up the portrait of a man torn between family love and state imperative (pictured above: Agamemnon interviewed while Clytemnestra waits with the two younger children - last night Clara Read and Bobby Smalldridge, real and touching). You wonder why the axe, or in this version “exhibit: silver labrys knife”, didn’t fall long before he comes back from the wars with an enemy girl in tow (the Cassandra of Hara Yannas, bursting into ancient Greek before we understand her prophecy. Yannas transforms into a fine judge in the equivalent of Aeschylus's closing Eumenides).

It doesn’t help that the only successful politician to whom Angus Wright’s under-authoritative Agamemnon comes close to resembling is John Major, in the voice, at least. He’s no less stilted in the “I’m home”s and “how has our day been”s which are supposed to set up the portrait of a man torn between family love and state imperative (pictured above: Agamemnon interviewed while Clytemnestra waits with the two younger children - last night Clara Read and Bobby Smalldridge, real and touching). You wonder why the axe, or in this version “exhibit: silver labrys knife”, didn’t fall long before he comes back from the wars with an enemy girl in tow (the Cassandra of Hara Yannas, bursting into ancient Greek before we understand her prophecy. Yannas transforms into a fine judge in the equivalent of Aeschylus's closing Eumenides).

At least the homecoming is where it gets interesting for, having finally reached the point where Aeschylus’s enacted drama starts, Icke is able to set up the acts of ritual repetition that are subtly different each time – the laying of the table, the ringing of the bell, the uncorking of the wine, who’s the main dynamic force within the House of Atreus. The original’s perfect symmetries may be unbalanced so that the screwing-up of Orestes and Electra to the sticking-point of their mother’s murder isn’t the centrepiece, but since Icke has the two surviving children grown up enough to be aware of Agamemnon’s end in the all-important bath, Orestes can be present in the official first play of the trilogy, trying to recall events to a psychiatrist (Lorna Brown) who later turns courtroom lawyer. Unfortunately his speeches come across as portentous in the wrong sense, at least in the not quite natural delivery of Luke Thompson. He's better than Jack Lowden, a very different Orestes in the Old Vic Electra, but still not strong enough. The highlight of the evening is the post-murder speech of Lia Williams’s Clytemnestra before we break for the second of the strictly timed intervals. Throughout she is the touchstone for what we can really understand in the drama, its beating, complicated heart. Unfortunately this is supposed to be an ensemble, and nobody else quite comes up to her level. Jessica Brown Findlay (picture above with Wright's ghost Agamemnon) in her stage debut as Electra looks plausibly grief-ravaged in Act Three but doesn’t quite carry on the torch: too much near-inaudible reflection, common to many in the cast of 10. It’s an interesting idea that she’s existed only in Orestes’ tortured mind, but these siblings receive performances of good-ish drama school level, no more.

The highlight of the evening is the post-murder speech of Lia Williams’s Clytemnestra before we break for the second of the strictly timed intervals. Throughout she is the touchstone for what we can really understand in the drama, its beating, complicated heart. Unfortunately this is supposed to be an ensemble, and nobody else quite comes up to her level. Jessica Brown Findlay (picture above with Wright's ghost Agamemnon) in her stage debut as Electra looks plausibly grief-ravaged in Act Three but doesn’t quite carry on the torch: too much near-inaudible reflection, common to many in the cast of 10. It’s an interesting idea that she’s existed only in Orestes’ tortured mind, but these siblings receive performances of good-ish drama school level, no more.

You wonder how Icke is going to deal with the Furies and the Athenian Court of Law. There’s only one demon sucking Orestes' lifeblood, Annie Firbank’s quietly implacable old woman circling the stage until judge Athene pronounces her “kindly”, while the rest of the cast turn courtroom questioners. It’s a clever idea, but just a little flat, and Icke havers over the psychology. Orestes murdered but he didn’t; “Is this a dream? Am I mad?” We’re almost back to the implausibility of the evening's starting point.

The accoutrements are uneven: a superbly wielded mirror/screen and backspace from the wonderful Hildegard Bechtler at her most austere, sound by Tom Gibbons that makes effective use of The Beach Boys’ "God Only Knows" but falls back on generic doomy choral stuff at odds with attempted realism. Only Williams truly moves us. Yet even when you may disagree with Icke’s take, there’s plenty of engagement for the mind, true to Almeida artistic director Rupert Goold's consistently executed manifesto, and that can’t be said of much other London theatre at the moment.

ROBERT ICKE: HIS CAREER SO FAR

ROBERT ICKE: HIS CAREER SO FAR

Boys. Ella Hickson’s new play is fuelled by testosterone but floats on nuance

Mr Burns. A startling vision of a post-apocalyptic world dominated by The Simpsons

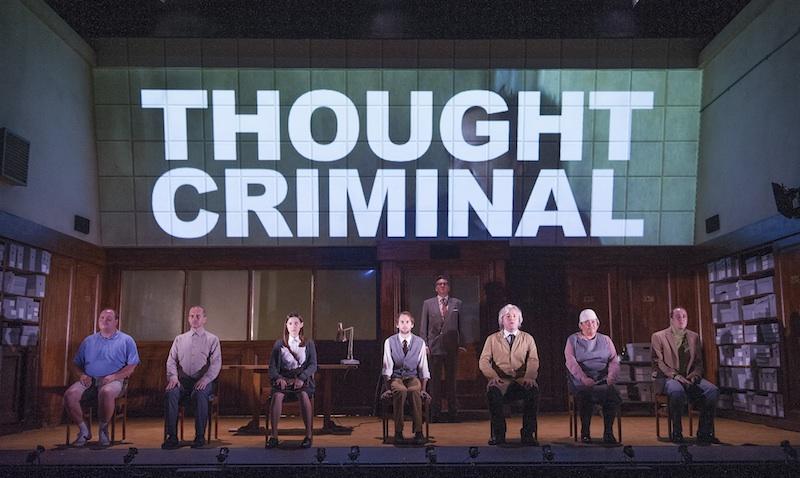

1984 (pictured by Tristram Kenton) Headlong's adaptation of George Orwell's novel is a theatrical coup

Uncle Vanya. Robert Icke's lengthy revival/reappraisal is largely a knockout

The Red Barn. David Hare’s latest is a superb adaptation of a Simenon thriller

Mary Stuart. Juliet Stevenson and Lia Williams electrify as four Schiller queens

Hamlet Predictably unpredictable performance from Andrew Scott subject to Icke's slow-burn clarity

Add comment