The weekly magazine Country Life was founded in 1897, and is now perhaps improbably owned by Time Inc UK. Its popular image among people who do not necessarily ever look at it is defined by the famous (or infamous) girls in pearls: those portraits of well-groomed fiancées, a kind of weekly visual equivalent of – say – Desert Island Discs for prosperous young aristos, which introduce the articles of each issue. There have been 6,000 such young belles since 1897, interspersed with an occasional Prince Harry or William – not wearing pearls.

This time round it was a Yorkshire lass, Ella Charlotte Clark, posed in a vast field, against a fence, accompanied by her faithful dog. Her fiancé, a serving Army officer, had suggested the photograph to Country Life; it is a badge of honour for a certain class. The weekly photograph, mostly accompanying engagement announcements, leads into the magazine’s articles after the bemused reader has turned over scores of pages of luscious property porn, country estates throughout the land up for sale, and elaborate fine and decorative arts advertisements. Country Life has a small audited circulation, less than 40,000, but its reach extends far beyond the waiting rooms of posh dentists, and its advertising (unmentioned here) is definitely read by the buyers and sellers of such gorgeous stuff.

Any reverse snobs - and snobs - out there, have a look

This sensitive, highly watchable programme, the first of three from director Jane Treays (last found embedded in another top-drawer British institution with Inside Claridge’s) is based on a year’s filming in the office and out and about. The result both confirmed conventional images of the magazine and simultaneously confounded and contradicted them. It set out its stall with the claim that the publication was an attempt to “capture the elusive soul of the English countryside”, the film’s subtitle “British Country Life” clearly indicating medium and message alike. It reminded us that in Britain at least the countryside is very, very muddy – literally, with views of gumboots squelching through the damp earth.

The calmly authoritative editor, Mark Hedges, bemoaned the lack of understanding on the part of urban England: Hedges was the editor of Horse and Hound before ascending to Country Life, so the land is in his blood. The statistics were disturbing if country values are to be, well, valued. Only 18% of the population lives in the country, while 80% live in the cities and the suburbs (yes, it does not quite add up – where is the missing two percent?).

And only four percent work on the land. Sir Roy Strong, with flowing white hair and beard, asserted that Country Life saw the whole island as a Greater England, a southern view, and that its security and continuity, in those villages, market towns and old families, was an artificial vision. We heard several times that it was but a dream; if the Englishman’s home was his castle (we glimpsed one or two), the garden was its earthly paradise.

And only four percent work on the land. Sir Roy Strong, with flowing white hair and beard, asserted that Country Life saw the whole island as a Greater England, a southern view, and that its security and continuity, in those villages, market towns and old families, was an artificial vision. We heard several times that it was but a dream; if the Englishman’s home was his castle (we glimpsed one or two), the garden was its earthly paradise.

Cue gardening editor, and a glimpse of one of the 4,000 gardens opened annually for charity, the chatelaine supervising and even baking endless Victoria sponges and coffee walnut cakes for the obligatory tea herself. Judith and Andrew Huxley were the owners; his role, he said, was as the unpaid third undergardener, but Mrs Huxley, giggling, said he was there to pay for it all: they raised £350 on their day, and a good time was had by all.

The running theme in this first instalment was tragic, though; think badgers, wild animals and farm animals. The leading protagonist was a Somerset dairy farmer, Maurice Durbin (pictured above), born to his trade, the modest natal homestead in the picture, complete with an enchanting four-year-old grandson, already helping to feed the calves. He told us that “the bloody do-gooders interfere with everything we do”. The epic horror story was tuberculosis in cattle, and Durbin’s prize herd of carefully bred Guernseys, among the finest in the country, was terminally threatened. The docile creatures, Bambi-eyed, were tested every 60 days, and forbidden, whether healthy or not, to visit the county shows, essentially under farm arrest.

We witnessed a testing, and saw two much-loved animals sent to the abattoir. The human family mourned. Each Guernsey cow had been raised from birth, had a name, and was worth some £3,000. No one knew what to do about the badgers: farmers on the ground want a cull, as protecting the badger has led to an explosion of setts, and are passionately resentful of the lack of understanding on the part of urbanites. Thirty-eight thousand cows have been killed so far.

We witnessed a testing, and saw two much-loved animals sent to the abattoir. The human family mourned. Each Guernsey cow had been raised from birth, had a name, and was worth some £3,000. No one knew what to do about the badgers: farmers on the ground want a cull, as protecting the badger has led to an explosion of setts, and are passionately resentful of the lack of understanding on the part of urbanites. Thirty-eight thousand cows have been killed so far.

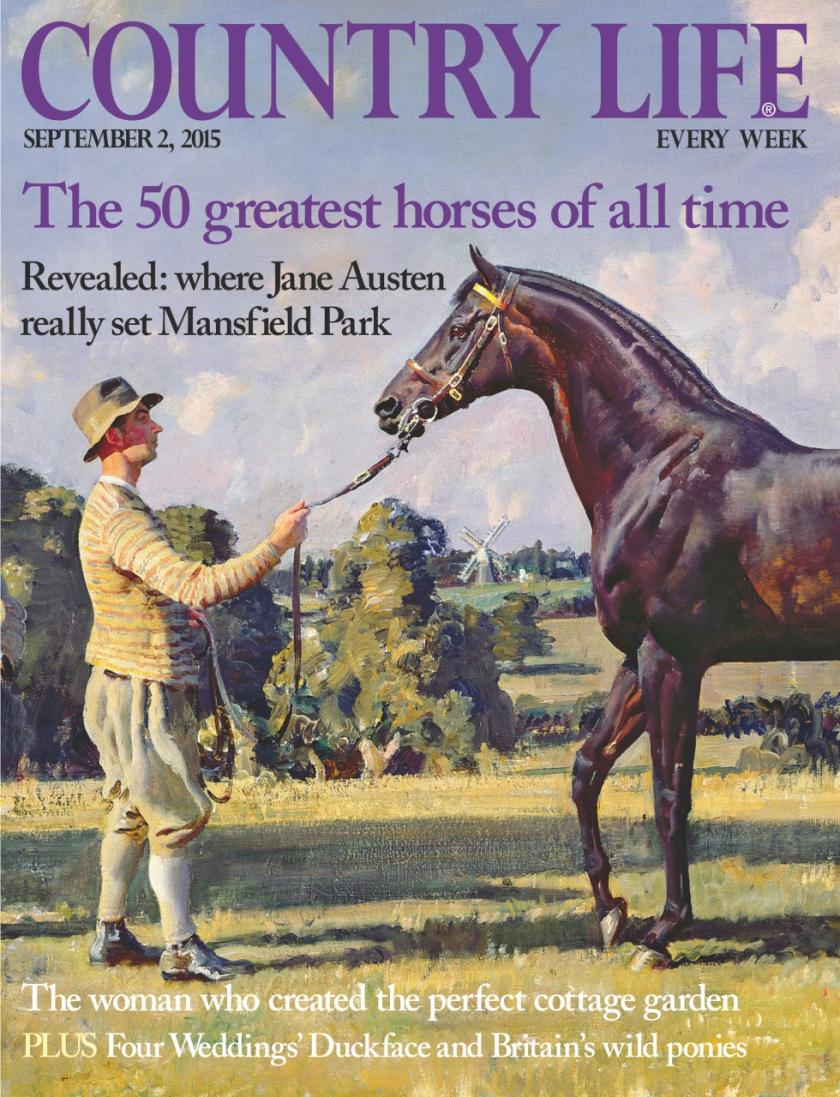

The heart of the magazine was defined as horses, gardens, architecture, and houses. We were offered a neatly extended visit with the magnificently knowledgeable Philip Mansell (himself a founder of the Court History Society, unmentioned here), owner of a Dorset home that has been in the same family for over three centuries. The architectural editor, John Goodall, and company came on a visit to see the new exhibitions and displays and write its history.

At times it almost sent itself up with attractive geniality: the magazine’s deputy editor, Rupert Uloth, has been a steward at the Royal Bath and West County Show, and came complete with the bowler hat that accompanies that role. He defined the event as a leading fashion show for animals, although looking thoughtfully at a huge bull also remarked there were not too many similarities to Kate Moss. Jane How, a down-to-earth farmer, pointed out the difficulties of keeping her white cattle pristine for show time; a sow of almost unimaginable size was wheeled about. But we were reminded that much farming is rather isolated, and that this was not only a fair in which prizes of all kinds were awarded to all kinds of domestic animals, but where information was exchanged and moral support in these difficult days for agriculture readily provided.

Mark Hedges exhibited a neatly surprising humour, despatching Country Life’s previous editor, the fastidious Clive Aslet, to report on yet another of England’s rituals, swan-upping on the Thames – 79 miles in five days, in a rag, tag and bobtail flotilla, catching and counting swans, with an occasional human dunking, and a very proud red-uniformed Queens Royal Swan Marker (David Barber, pictured above left, left); this annual foray is centuries-old.

This was simultaneously affectionate, hilarious – intentionally and sometimes perhaps not – extremely informative, and surprisingly compelling viewing. Any reverse snobs – and snobs – out there, have a look. And with any luck, it might do wonders for the circulation.

Add comment