It was the year that everyone got just a little hysterical about Damien Hirst. That and the art market that made him. But that didn’t keep the visitors away from his retrospective at Tate Modern. The exhibition had more crowds than Wembley Stadium, or at least more than for any other exhibition in Tate Modern’s 12-year history (and possibly for any exhibition since Tate records began). It was cleverly curated (i.e. heavily edited) so it wasn’t half as execrable as some critics claimed it was (or said it would be before seeing it). And at least it reminded us why anyone had made such a fuss about the YBAs in the first place.

This was an exhibition that made the heart do joyful somersaults

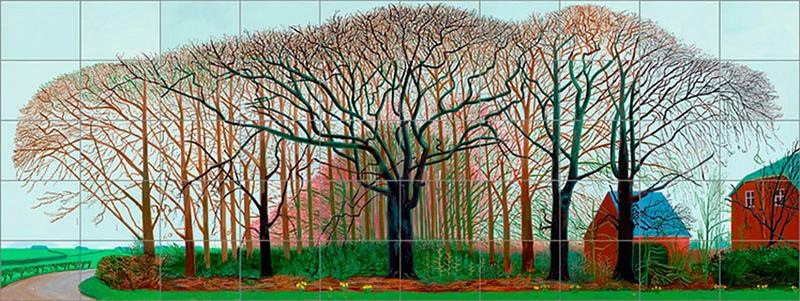

It was also the year that divided critics on David Hockney. Someone at The Daily Telegraph even claimed the wonderfully exuberant survey of Hockney’s East Yorkshire landscapes, The Bigger Picture at the Royal Academy, made the artist look like a “Sunday painter”, while some blanched at his acid-bright colours. But they’re wrong, just wrong. The survey showed what a complete master Hockney is and continues to be in his eighth decade. Not only does he surpass anyone I know with his exquisite draftsmanship, but his colours simply sing. This was an exhibition that made the heart do joyful somersaults.

From zingy colours to dun brown – a retrospective of Hockney’s old buddy Lucian Freud, who died in 2011, was at the National Portrait Gallery. There are some who prefer Freud’s later nudes over his earlier stylised paintings, but I’m really not one of them. I love Freud pre-1950 – apart from anything else he shows himself to be a surprisingly good and subtle colourist. And what powerful, anguished portraits – his first wife arresting us with her intense gaze while half strangling that poor kitten whose startled look echoes her own; and that strange little girl in her blue coat staring us out as the big hand of her father restrains her. It was bliss to see these early paintings, and among his later ones I was just grateful that there was no Queen, no Jerry Hall or Kate Moss.

It was also the year that many claim was the strongest by far for the Turner Prize (until 6 January) even though it included the weakest artist for some time – it was bewildering to find the performance artist Spartacus Chetwynd here. However, Luke Fowler’s 93-minute film (yes, 93 minutes) about counter-culture psychiatrist RD Laing was superb. How anyone could find this profoundly moving slice of social history, beautifully spliced and edited, remotely boring is beyond me. And though it wasn’t Fowler who won in the end, another film artist, Elizabeth Price, was a more than credible winner, thus proving that film art needn't be seen as dull art.

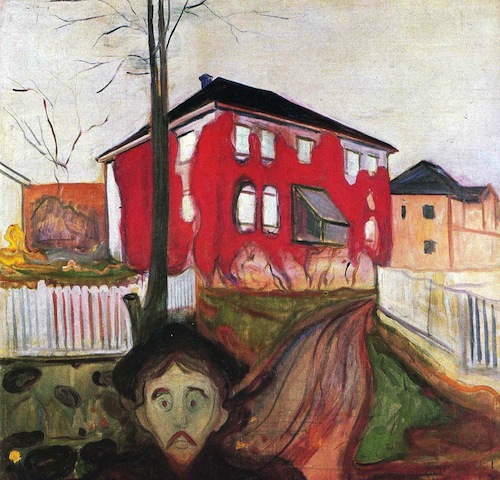

Other memorable shows included Gillian Wearing at the Whitechapel Gallery, Edvard Munch at Tate Modern (pictured below: Red Virginia Creeper, 1898-1900), and the Hayward Gallery’s Invisible, which at first sounded like it might be a bit of a joke but turned out to be a fascinating exploration of the power of the viewer’s imagination to complete an artwork. Meanwhile, the British Museum finally got its hands on a complete set of Picasso’s Vollard Suite to add to their extensive national collection of drawings and prints, and The Queen’s Gallery presented their glorious exhibition The Northern Renaissance: From Dürer to Holbein (until April).

The Royal Academy had two must-see shows which topped and tailed the year. As the year began with a splash with Hockney, so it ended with a bang with Bronze, a survey of 5000 years of bronze sculpture. From Praxiteles (probably) to rare casts from Willem de Kooning, it proved a stunning selection.

The Royal Academy had two must-see shows which topped and tailed the year. As the year began with a splash with Hockney, so it ended with a bang with Bronze, a survey of 5000 years of bronze sculpture. From Praxiteles (probably) to rare casts from Willem de Kooning, it proved a stunning selection.

Finally, I was completely taken by surprise at just how much I enjoyed the Barbican’s Everything was Moving: Photography from the 60s to the 70s (until 13 January), not least because the title was so unpromising. The survey eschewed the typical done-to-death swinging Sixties celebrity/pop cultural trawl and, completely international in scope, was profoundly powerful with its hard-hitting politics. Particularly memorable were the early photographs of Ukrainian Boris Mikhailov (main picture: untitled), whose playfully subversive, layered colour images blew me away. As did Bruce Davidson’s black and white series Freedom Riders, documenting the American civil rights movement.

Amid pretty strong competition Everything Was Moving is probably my exhibition of the year. But for making my heart hum with pure pleasure Hockney’s exuberant landscapes proved to be just priceless.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment