Art exhibitions hardly seem comparable with battery farming, and yet just as our insatiable appetite for cheap meat gives rise to some troubling consequences, so too does the demand for definitive exhibitions that require vulnerable works of art to be shipped around the world. And so it really is a cause for celebration that an exhibition exploring Eugène Delacroix’s influence in the 50 years following his death maintains its focus, argues its case and thoroughly immerses us in his work, without actually showing us any of his best known paintings.

We are left to guess at the sheer scale of The Death of Sardanapulus, 1827-28, all four by five hulking metres of it remaining, thank goodness, in the Louvre, and we can only imagine the impact that painting must have had when it made its debut in the Paris Salon. In its place is a much smaller copy, made by Delacroix some years after the original, and in it he emphasises – exaggerates even – all of the scandalous novelties that had so enraged the critics of the time (pictured below right: The Death of Sardanapulus, reduced replica, 1846). Tiny as it is, the copy gives a surprisingly evocative sense of the loose brushwork, the seemingly chaotic composition, the sensuous enjoyment of colour, fabric and flesh, and the decadent, exotic themes of sex and death that had it condemned as an outrageous break with academic tradition.

It is hard now to fully appreciate just how tedious French painting had become. While the flame of neo-classicism had been rekindled by Jacques-Louis David in the service of the French republic, this was only briefly so and the inflexible rules of the academy stifled the expressive qualities of painting in favour of didactic, moralising themes, typically depicting events from literature or the distant past in a manner that was both dry and slavishly classicising.

It is hard now to fully appreciate just how tedious French painting had become. While the flame of neo-classicism had been rekindled by Jacques-Louis David in the service of the French republic, this was only briefly so and the inflexible rules of the academy stifled the expressive qualities of painting in favour of didactic, moralising themes, typically depicting events from literature or the distant past in a manner that was both dry and slavishly classicising.

Delacroix’s impatience with the prescriptive teachings of the academy is glimpsed in moments of high drama. Exhilarating flurries of brushwork and daring combinations of paint not only reveal, and revel in, the act of painting itself, so carefully disguised in the invisible brushstrokes of academic painters like Ingres, but leave us to mix colours optically, with colours placed side by side on the canvas, not mixed on the palette.

In a sketch for his ceiling painting in the Louvre’s Galerie d’Apollon, Apollo himself is barely discernible: it is as if we are looking directly at the sun, its dazzling effect leaving the painting’s subject shockingly indistinct, a flash of light and motion. Could there be a more marvellous or compelling way to depict the sun god in his chariot?

Of course any exhibition that fêtes an individual is bound to inflict casualties, and it is hard not to feel a pang of regret for Théodore Géricault, who has had to go unmentioned to allow the show its narrative focus. And yet Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, 1818-19, redeployed the heroic nude, subverting the revered genre of history painting by depicting a contemporary event in a visceral, highly emotive way, and Géricault shared with Delacroix many of the progressive ideas about colour that would cement Delacroix’s elevated status amongst artists of the future.

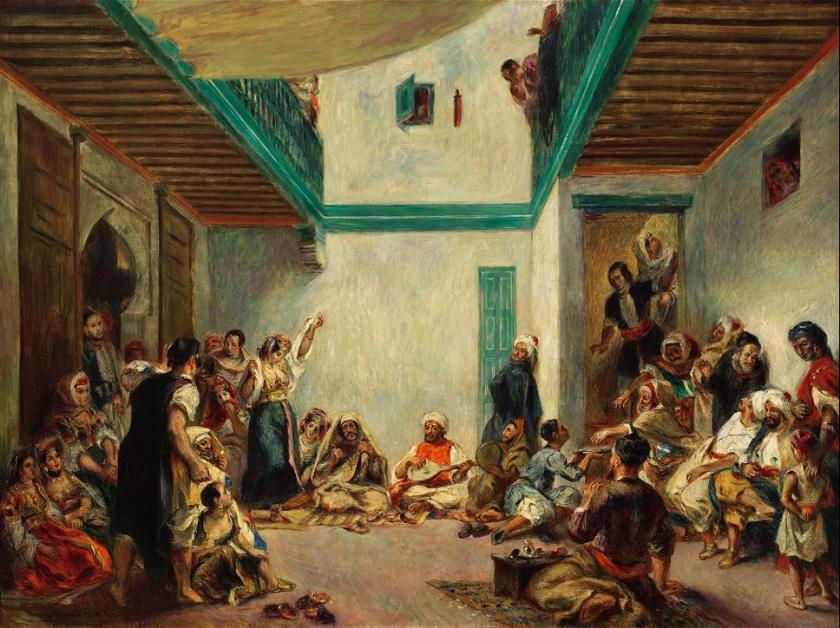

Exactly what it was that artists came to appreciate in his work is beautifully elucidated in the copies of Delacroix’s paintings made by Renoir, in particular. We don’t get to see the original, and yet somehow Renoir’s copy of The Jewish Wedding in Morocco, c.1875, makes plain all that the younger man admired (main picture).

For all his enjoyment of the exotic, forbidden subject-matter, it is Renoir’s treatment of the wall that is most telling. It is a white wall, and yet it is composed of a rainbow of colours, short vertical dashes of blue, green and mauve mimicking the fall of light on a somewhat irregular surface. And he makes much of Delacroix’s shadows, painting them in vivid colours that evoke sparkling, dappling light, and with not a brown or black in sight.

For all his enjoyment of the exotic, forbidden subject-matter, it is Renoir’s treatment of the wall that is most telling. It is a white wall, and yet it is composed of a rainbow of colours, short vertical dashes of blue, green and mauve mimicking the fall of light on a somewhat irregular surface. And he makes much of Delacroix’s shadows, painting them in vivid colours that evoke sparkling, dappling light, and with not a brown or black in sight.

Just as in his own time Delacroix courted controversy with his colourful shadows, there was mischief too in his embrace of the lowly genre of flower painting. If history painting was the most prestigious of genres, flower painting and still-life was firmly at the bottom of the heap, regarded as intellectually void and technically straightforward.

Delacroix’s A Basket of Fruit in a Flower Garden, 1848-49, is almost monumental in scale, and the outdoor setting introduces a certain ambiguity to the scene as well as complicating the pictorial space. But much as we might read this painting, and others like it as a deliberately provocative act, cocking a snook at the academy, flower painting provided above all a unique opportunity for Delacroix to focus on a sensuous exploration of colour and texture.

Artists like Gauguin, Van Gogh and Redon followed his lead, with Gauguin’s A Vase of Flowers, 1896, exploring the decorative potential of fields of colour, and the intensity achieved by certain juxtapositions (pictured above left). Informing Pointillism and Impressionism, the scintillating effects achieved by laying strokes of contrasting paint next to and within colour fields, the technique Delacroix called flochetage was a legacy that remained remarkably intact, from the Death of Sardanapulus, to Matisse's Luxe, Calme et Volupté, 1904.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment