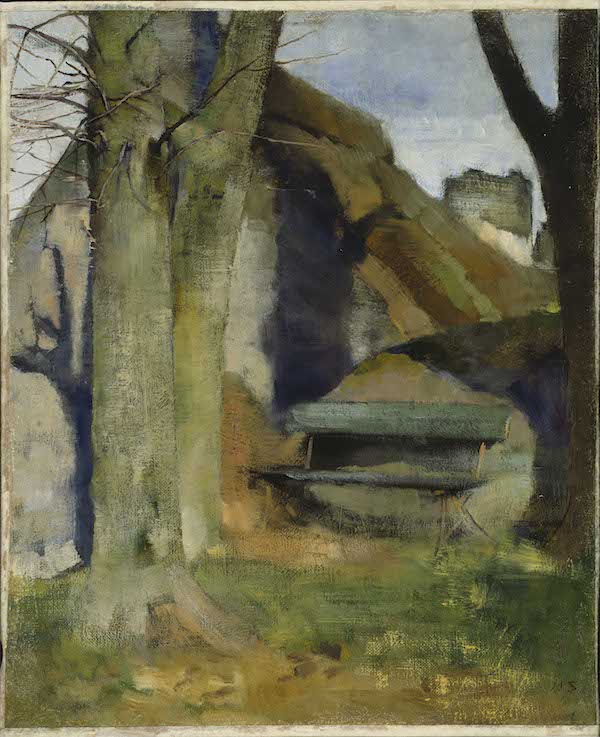

Light creeps under the church door. Entering as a slice of burning white, it softens and blues into the stone interior, seeming to make the walls glow from the inside. Beneath the lintel, a milder slot of sun pours upwards. To the right, a plain column, only half in the composition, supports an arch which merges with the back wall, disappearing against its horizontal plane. The chapel is empty but its stillness feels peopled. Here, absence is watchful.

The Door, 1884, was painted at the Chapelle de Trémalo in Pont Aven by Finnish artist Helene Schjerfbeck. A grant from the Finnish Senate had previously enabled her to live and study in France from 1880-82 and, having returned for a year, she shuttled between between the nascent artists’ colony and Paris. The first time around she had established friendships with other female artists including Marianne Preindlsberger and Maria Wiik. Now, she was engaged to be married – a situation that would prove short-lived. Her fiancé broke off the engagement on her return to Finland that summer. Schjerfbeck’s request to friends and acquaintances that they destroy all mention of him in their correspondence resulted in an obliteration so complete that his identity remains a mystery today.

Watchful absences and disappearing people – Schjerfbeck’s work is recognised and lauded in Finland and other Scandinavian countries but fairly unknown in the UK. The Royal Academy’s latest exhibition aims to rectify this. It strives to strike a balance between paintings which often hover between a sense of presence and the act of erasure, while foregrounding her idiosyncratic technique – the result of scoring, sanding and rubbing away layers of paint to create planes of soft colour.

Watchful absences and disappearing people – Schjerfbeck’s work is recognised and lauded in Finland and other Scandinavian countries but fairly unknown in the UK. The Royal Academy’s latest exhibition aims to rectify this. It strives to strike a balance between paintings which often hover between a sense of presence and the act of erasure, while foregrounding her idiosyncratic technique – the result of scoring, sanding and rubbing away layers of paint to create planes of soft colour.

Another early painting, The Bakery, 1887, is again notable in that no bakers appear. Though she paid to set up her easel in the bakery, human presence remains only by implication – through the glowing rows of loaves lined up for weighing and the roaring wood oven demanding regular fuel. Likewise Clothes Drying, 1883, in which linen laid out on grass under sun suggests a type of working woman captured in routine domesticity, her labour further emphasised by the fruit netting at the edge of the painting. Again, these women are remarkable for their absence.

By contrast, the candid portrait My Mother, 1902, is remarkably ambivalent. Schjerfbeck’s mother, Olga, sits in a red rocking chair, a book open on her lap. Her clothes are heavy and black, the wall is blue, her hair is white. The chair is the same as appears in The Seamstress (The Working Woman), 1905. But while she is painted in a formal side-on pose resembling Whistler’s Arrangement in Grey and Black No 1, 1871, Olga is pivoted away, as if choosing to face the wall – it is a portrait without a face. Whether the painting portrays the fragile intimacy between a mother and daughter living in a single room apartment or the collapse of those very bonds under the weight of reciprocal demands, Olga’s pose either requests respectful distance or actively repels attention. Either way, there is a clear sense that any closer would be an intrusion – viewers are locked out.

Despite receiving grants and awards by the Finnish government, Schjerfbeck never had quite enough money to travel when and where she wished. Following her return from France, she mostly remained in Finland and – to her regret – never married. A fascination with fashion remained largely unfulfilled except through reading magazines and mainly found outlet in portraying local girls as feline-eyed garçonnes in androgynous cloche hats. She often didn’t show the finished paintings to the sitter. While her artistic talent was prodigious (aged 11 she was arranged a free place to study at the Finnish Art Society in Helsinki, her work having been spotted by Adolf von Becker), a hip injury from falling down stairs as a young girl meant she walked with a limp throughout her life. The accident left her frail and susceptible to bouts of debilitating pain.

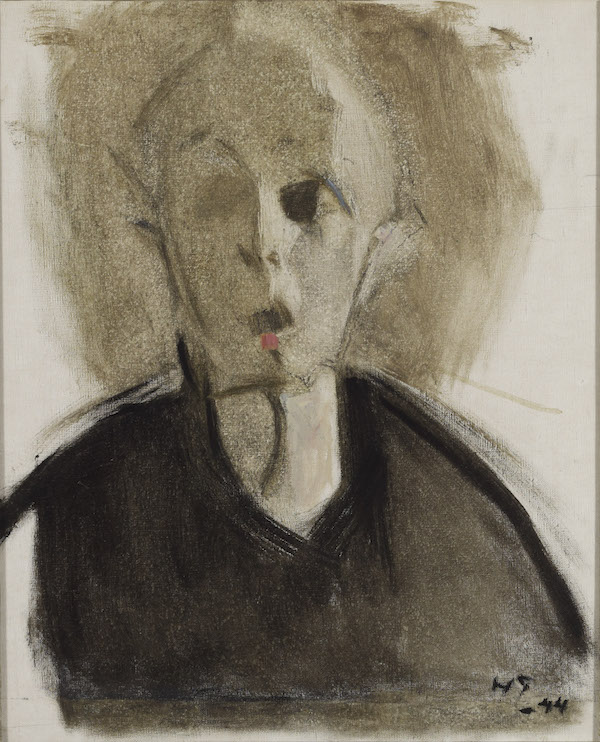

The centre-piece of the exhibition is a room dedicated to a series of self-portraits made between the ages of 22 and 83, which chart her evolving style and physical decay. Beginning with a pencil sketch, her renditions soon free themselves from naturalism and loosen into abstraction. Some, nevertheless, cloy. Self-portrait, 1880-84 is sentimental while Self-portrait, A Study, 1915 is more illustration than painting. Yet from the same year, Self-Portrait, Black Background, 1915 (pictured top) captures her as redoubtable and elegant with experimentally strident and graphic colour. Self-Portrait with Red Spot, 1944 (pictured left) from the penultimate year of her life, fades her face horrifyingly into the background – the daub of red might as easily be lipstick as blood or a sign of life. Either way, it hovers violently over lips which open in a terse howl.

The centre-piece of the exhibition is a room dedicated to a series of self-portraits made between the ages of 22 and 83, which chart her evolving style and physical decay. Beginning with a pencil sketch, her renditions soon free themselves from naturalism and loosen into abstraction. Some, nevertheless, cloy. Self-portrait, 1880-84 is sentimental while Self-portrait, A Study, 1915 is more illustration than painting. Yet from the same year, Self-Portrait, Black Background, 1915 (pictured top) captures her as redoubtable and elegant with experimentally strident and graphic colour. Self-Portrait with Red Spot, 1944 (pictured left) from the penultimate year of her life, fades her face horrifyingly into the background – the daub of red might as easily be lipstick as blood or a sign of life. Either way, it hovers violently over lips which open in a terse howl.

Her still-lives tread similar territory. Pumpkins, 1935, deploys thick impasto and hazy washes in a particularly modern style. Against the umber plate and pale wall the squash stand as a vibrant harvest. Green climbs the side of the largest, central pumpkin as if it were still surrounded by vegetation. A dark, black one at the front sounds a solemn note of warning. In Three Pears on a Plate, 1945, painted the year she died, the fruit rests on a tongue of black extending towards the front of the frame. Schjerfbeck often switched between canvases while working and, like the portraits, this still-life seems to suggest the inextricability of mortality from the condition of being alive. The dark plate provides both stage and reason for the pears. As in her early work, the absence of people again tells us the most about them.

- Helene Schjerfbeck is at the Royal Academy unitl 27 October 2019

- More visual arts on theartsdesk

Add comment