There is nothing erotic or titillating about The Institute of Sexology, an exhibition the Wellcome Collection plans to keep open for a year. Those expecting a display of fertility symbols, fetish objects, kinky clothing or sex aids down the ages will be deeply disappointed. Just about enough objects and images are included to keep you interested, but the bulk of the show is not dedicated to sexual practices but to the 19th- and 20th-century doctors, anthropologists and psychologists who spent their lives studying sexual behaviour.

And therein lies the problem. The exhibition format makes it impossible to do justice to the work of these experts; so you have to be content with snippets of information that, at best, might prompt you to do some further research. A photo of the Berlin library of sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, taken in 1933 after it had been trashed by government-sanctioned rioters, introduces the topic of sexual “deviance” and the acceptance or suppression of difference. Hitler’s attack was provoked by Hirschfeld’s efforts to seek justice for people being persecuted for their sexual preferences.

Begun in 2006, Zanele Muholi’s portraits of black gays and lesbians in South Africa are a reminder that prejudice is still very much alive today. Gaps in the display pay tribute to those who have been killed since she photographed them.

Begun in 2006, Zanele Muholi’s portraits of black gays and lesbians in South Africa are a reminder that prejudice is still very much alive today. Gaps in the display pay tribute to those who have been killed since she photographed them.

Richard von Krafft-Ebbing had previously documented cases of “deviance”, but perhaps wisely wrote key passages of his learned tome, Psychopathia Sexualis, 1886, in Latin to prevent lay readers from accessing the information. From his collection of erotica come postcards of a masked man wearing a pink tutu (pictured left) and a woman riding a man on all fours with a bridle in his mouth.

Among the items from Henry Wellcome’s collection are some phallic bronze amulets that the Romans would have hung in doorways to ward off evil spirits, a porcelain fruit that opens to reveal a couple making love, a cowrie shell that opens to reveal a painting of a woman locked in a chastity belt (pictured below right), phallic Peruvian jugs and tiny figurines of the Egyptian god Horus portrayed as a child clutching a mountainous erection. Wellcome saw these as an indication that religions originate in phallic worship and fertility cults.

The exhibition is divided into sections. The Consulting Room is devoted to Sigmund Freud, famous for his “talking cure”, and Marie Stopes, who advised people “not to think about your subconscious mind”, since “all the filthiness of this psychoanalysis does unspeakable harm.” Yet she was hugely influential in recognising women’s right to sexual pleasure without the burden of constant childbirth. Starting with a horse-drawn caravan (main picture), by the late 1920s she had established a nationwide network of birth control clinics and provided products like the Racial Cap, a rubber diaphragm enabling women to control their fertility. As a member of the Eugenics Society, she aimed to lower the birthrate among “undesirables”; but no matter how unpleasant her politics, her influence was incredibly liberating. She compiled a chart recording The Symptoms of Sexual Excitement in Solitude, which contains the comment, “One or two orgasms during the day, but they were clearly induced by thought, also I was experimenting in areas of sensitiveness”.

The exhibition is divided into sections. The Consulting Room is devoted to Sigmund Freud, famous for his “talking cure”, and Marie Stopes, who advised people “not to think about your subconscious mind”, since “all the filthiness of this psychoanalysis does unspeakable harm.” Yet she was hugely influential in recognising women’s right to sexual pleasure without the burden of constant childbirth. Starting with a horse-drawn caravan (main picture), by the late 1920s she had established a nationwide network of birth control clinics and provided products like the Racial Cap, a rubber diaphragm enabling women to control their fertility. As a member of the Eugenics Society, she aimed to lower the birthrate among “undesirables”; but no matter how unpleasant her politics, her influence was incredibly liberating. She compiled a chart recording The Symptoms of Sexual Excitement in Solitude, which contains the comment, “One or two orgasms during the day, but they were clearly induced by thought, also I was experimenting in areas of sensitiveness”.

The Tent looks at the work of anthropologists such as Margaret Mead who caused a stir in American when, in 1928, she published her findings revealing that Samoan girls not only masturbated but had homosexual as well as heterosexual relations. Many Americans were similarly outraged by Wilhelm Reich’s Orgone Accumulator, a chamber made from plywood, insulating board, sheet metal and fibreglass, that supposedly trapped and stored energy; a session inside the box was said to improve one’s general health and boost one’s libido. In his sci-fi comedy Sleeper, 1973, Woody Allen emerges from an Orgasmatron – a spoof on Reich’s Orgone Accumulator – in a state of ecstatic burn out.

For me, the most interesting exhibit is Richerche Three, 2013, a film made by Sharon Hayes in an all-women’s college in western Massachusetts reputed to be a hotbed of lesbianism, a claim that seemed to be borne out by the gay and transgender students she interviewed about their attitudes towards sex. But the soundtrack permeates the space to an annoying degree; I thought a debate was raging in the next room and longed for it to end.

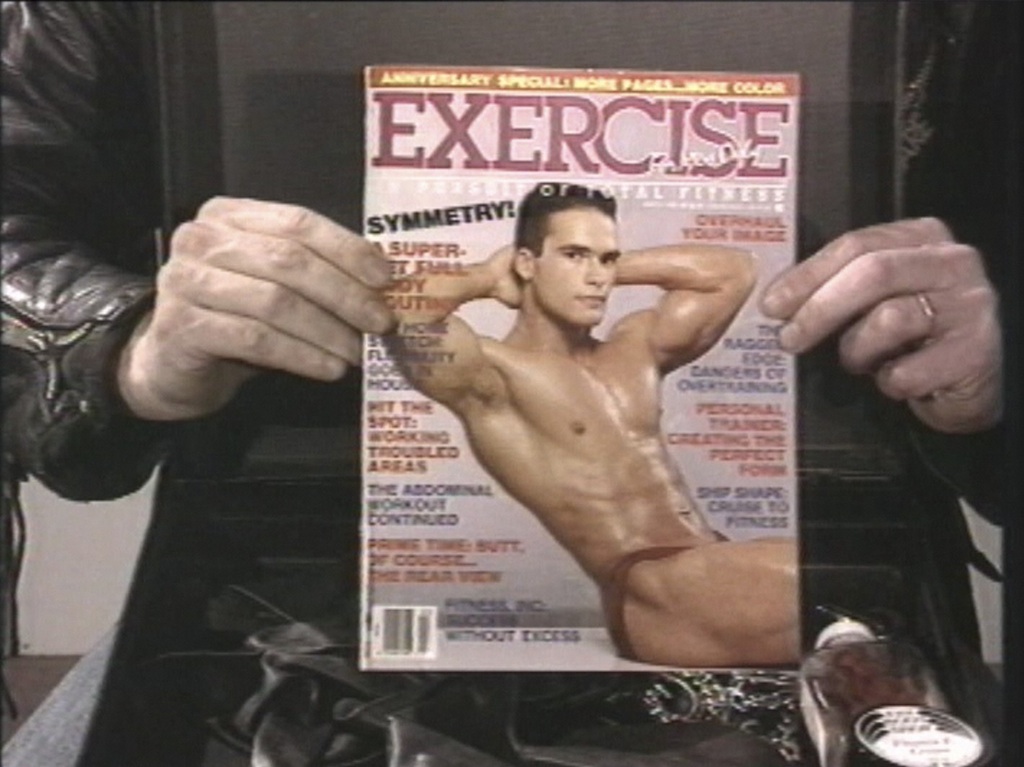

The exhibition ends with another reminder of the way society endeavours to control people’s sexual behaviour (and usually fails). Pedagogue (pictured above) is a film made in 1988 by Neil Bartlett and Stuart Marshall in response to Clause 28, which outlawed the promotion of homosexuality in schools and colleges. Bartlett opens his briefcase to reveal rubber gloves, underwear and a gay porn magazine, upon which both male and female students at Trent Polytechnic (now Nottingham Trent University) confess to becoming lesbians as a result of his tuition.

The exhibition ends with another reminder of the way society endeavours to control people’s sexual behaviour (and usually fails). Pedagogue (pictured above) is a film made in 1988 by Neil Bartlett and Stuart Marshall in response to Clause 28, which outlawed the promotion of homosexuality in schools and colleges. Bartlett opens his briefcase to reveal rubber gloves, underwear and a gay porn magazine, upon which both male and female students at Trent Polytechnic (now Nottingham Trent University) confess to becoming lesbians as a result of his tuition.

This absurdist parody is the nearest we get to addressing issues that are of burning importance, such as paedophilia and female genital mutilation. A debate about the degree to which the state should attempt to control the sexual behaviour of its citizens would make the exhibition feel less like a stroll down memory lane. A discussion concerning the duty of the state to protect minors from sexual predators and sexual practices which are nasty and dangerous would set the building on fire – metaphorically speaking.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment