Lubaina Himid, Tate Modern review – more explication please | reviews, news & interviews

Lubaina Himid, Tate Modern review – more explication please

Lubaina Himid, Tate Modern review – more explication please

A carnival of characters looking forwards as well as backwards

Lubaina Himid won the Turner Prize in 2017 for the retrospective she held jointly at Modern Art, Oxford and Spike Island, Bristol. My review of those shows ended with the question: “Which gallery will follow the examples of Oxford and Bristol and offer Lubaina Himid the London retrospective she so richly deserves?”

Four years later, here it is – at Tate Modern. But whereas those joint exhibitions revealed the richness and emotional depth of Himid’s work, this show leaves the viewer somewhat stranded, without the information needed to fully engage with subject matter that is often inscrutable.

Her work benefits hugely from knowing something of its origins. Reading my earlier review, I was amazed by the amount I understood then compared with the little I gleaned this time round. Take, for instance, Plan B a series of paintings made during a residency in St Ives in the late 1990s. Himid’s studio was a lifeguard’s hut and its proximity to the sea engendered thoughts of dangerous ocean crossings and enforced migrations, especially the horrors of the slave trade.

Beach House features a rickety wooden structure silhouetted against a pink sky, virulent orange sand and oppressively dark sea; the flimsy hut looks set to collapse in the next storm. Other pictures show empty rooms furnished, like reception centres, with a scattering of spindly chairs; these are juxtaposed with panels of writing describing hazardous journeys. “Endless days of running and hiding”, reads one; “our fear was unbearable…hearing strange, terrifying noises”. Singing united the group and gave them “the strength to survive long enough to enjoy our freedom.”

Beach House features a rickety wooden structure silhouetted against a pink sky, virulent orange sand and oppressively dark sea; the flimsy hut looks set to collapse in the next storm. Other pictures show empty rooms furnished, like reception centres, with a scattering of spindly chairs; these are juxtaposed with panels of writing describing hazardous journeys. “Endless days of running and hiding”, reads one; “our fear was unbearable…hearing strange, terrifying noises”. Singing united the group and gave them “the strength to survive long enough to enjoy our freedom.”

The exhibition booklet doesn’t mention the residency, Himid’s fear of drowning, her own migration from Zanzibar to Preston, or the sea as a recurring motif in her work. This absence of personal detail shifts one’s understanding of the series. Evocations of historical trauma are replaced by thoughts of more immediate disasters, such as climate change and its consequences – violent storms, rising sea levels and displaced people attempting dangerous crossings in flimsy boats. And while emphasising the work’s ongoing relevance, this lack of information robs it of personal and historical significance.

Old Boat, New Money, 2019 (pictured below) harks directly back to the slave trade and, this time, a quote from Himid makes the connection clear. ‘What would it be like if this happened to me?” she asks. “How terrifying would this be … in a moving, stinking space, not knowing that it’s a wooden sailing ship, on this stuff that I don’t know is the sea?” Once you know the references, the installation – a wave-like formation of planks leaning against the wall accompanied by sounds of the sea and a creaking wooden vessel – is as evocative as her words, but without them, it loses its meaning.

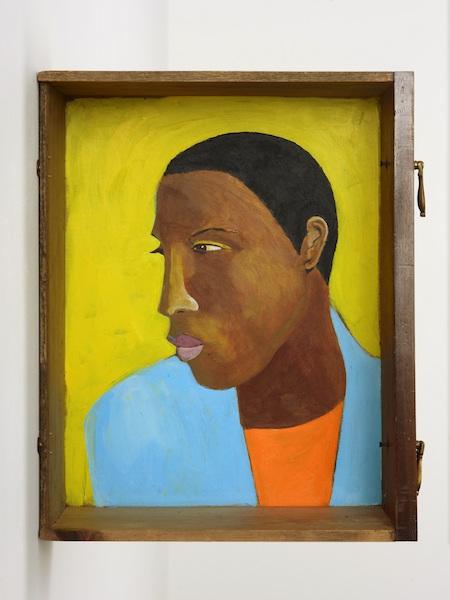

Some people, it seems, make the crossing in style. Between the Two My Heart is Balanced, 1991 (main picture) shows two women in African dress braving turbulent waters in a small boat. The title evokes the experience of living between two cultures and these women proudly display their origins while calmly shredding the pile of maps stacked between them. This is a symbolic attempt, perhaps, to disrupt the trade routes along which slavers plied their trade. Painted inside various drawers are a series of portraits. It’s a wonderfully inventive way of commemorating the African slaves who once worked for the gentry and whose very existence has become invisible. I imagine Man in a shirt drawer, 2018 (pictured above right) to be the valet of some toff whose portrait graces the walls of a stately home while his servant is long forgotten.

Painted inside various drawers are a series of portraits. It’s a wonderfully inventive way of commemorating the African slaves who once worked for the gentry and whose very existence has become invisible. I imagine Man in a shirt drawer, 2018 (pictured above right) to be the valet of some toff whose portrait graces the walls of a stately home while his servant is long forgotten.

Himid’s other paintings can’t be understood so readily, though. I have no idea who the woman is in Slice Ten Lemons, 2020 or what, in other pictures, the impeccably dressed men are negotiating with such awkward glances. I am left to my own devices, wondering at the shallow spaces and inverted perspectives the artist creates as a backdrop for people who interact with strangely wooden gestures (pictured above: Ball on Shipboard, 2018).

These hieratic figures are more like cardboard cut-outs than flesh and blood people. This brings me to Naming the Money 2005, an installation of 100 cut-out figures evoking the African slaves who worked in the courts of 18th century Europe. Himid’s wonderful sculpture is represented only by a soundpiece that evokes amazing resilience in the face of loss of identity, community and freedom: “I used to cure diseases, now I make the tea; but I am never ill”. It would have been so much more powerful, though, with at least some of the figures in attendance and would have meant the show ended with a bang rather than a whisper. The chilling installation that closes her retrospective implies a new departure concerned more with present issues than former wrongs. The exhibition is staged as a series of questions, the last one being Do you want an easy life? which is scrawled on the frame of a full-sized bike shed and smoking shelter. This dismal structure provides a dystopian view of ugly urban spaces that offer little comfort or security and are quickly vandalised by disgruntled youth. The stark contrast between the vivid colours of Himid’s paintings and the pallor of this new work seems to pressage a future that could be far from bright.

The chilling installation that closes her retrospective implies a new departure concerned more with present issues than former wrongs. The exhibition is staged as a series of questions, the last one being Do you want an easy life? which is scrawled on the frame of a full-sized bike shed and smoking shelter. This dismal structure provides a dystopian view of ugly urban spaces that offer little comfort or security and are quickly vandalised by disgruntled youth. The stark contrast between the vivid colours of Himid’s paintings and the pallor of this new work seems to pressage a future that could be far from bright.

- Lubaina Himid is at Tate Modern until 3rd July 2022

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Comments

This review resonates with me